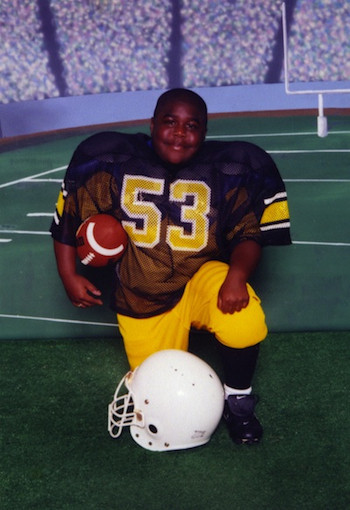

Kellen Bolden was only 10 years old when an asthma attack took his life, but his mom still remembers him as a "little man" with big aspirations.

"He often said to himself, 'Good morning, Mr. Millionaire,'" recalled Rhonda Mitchell. Kellen's dreams, she said, weren't confined to the limits of his hometown, Jonesboro, Ga., a predominantly minority, low-income community about 20 miles south of Atlanta.

Much like its bigger neighbor to the north, and a number of other cities across the country, Jonesboro has long faced air pollution problems.

"We know that air quality is unacceptable in many places," said Christopher Paul, a graduate student in environmental policy at Duke University. "This is just one of a number of assaults on children's well-being that makes it harder to lead healthy, successful lives."

Paul is a researcher on a study published last year that describes disparities in air quality around the U.S. By pairing census data with air pollution levels from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency's monitoring network, his team found that low-income and minority groups -- in particular, poor children of color -- tend to be most exposed to air pollution.

Disadvantaged kids not only breathe disproportionate amounts bad air, but they also can be more vulnerable to the ill effects of that bad air. As The Huffington Post reported in March, asthma is likely the most notorious of these ailments. Nearly one in four Hispanic and Puerto Rican kids living in poverty in the U.S. has been diagnosed with the condition that can cause wheezing, coughing, breathlessness and chest tightness, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. That compares with about one in 13 middle-class or wealthy white children. (The agency also reports similar disparities in exposures to air pollution.)

Air pollution, Mitchell said, was a major trigger for Kellen's asthma. "On smoggy days, it seemed like he couldn't ever get enough air," she said, noting that the avid football player stayed indoors when these dangerous conditions hit Jonesboro.

Just why lower income families more commonly reside in places with dirty air is not clear, said Janice Nolen, assistant vice president of national policy and advocacy at the American Lung Association, which released its annual State of the Air report last month. Power plants and industrial boilers might be constructed in poor neighborhoods. Or it may be that areas housing such facilities, or that are bordered by heavily trafficked roads, simply offer cheaper housing. Researchers recently traced back the historical influx of African Americans into western Louisville, Ky., and found that this occurred after the arrival of polluting industries that gave the area its nickname of "Rubbertown".

"Richer neighborhoods are not necessarily built near major highways or downwind from factories," noted Nolen.

Regardless, the differences in how much toxic air children breathe may not be the only explanation for the disparities in air pollution-related children's health problems, experts said. Take, for example, the city blocks that extend north and south of East 96th Street in Manhattan, New York, the rough dividing line between the neighborhoods of East Harlem and the Upper East Side.

Nearly one of every three kids in East Harlem suffers from asthma. In the more affluent Upper East Side, the rate is less than 10 percent. Yet both neighborhoods have been found to have poor air quality due in large part to diesel truck and bus traffic and old buildings that still burn dirty heating oil.

How could kids living within walking distance of one another face such disparate risks?

"You have to layer the air pollution on top of other existing social disparities," explained Cecil Corbin-Mark, deputy director for the Harlem-based nonprofit WE ACT for Environmental justice. "What happens when a child has an asthma attack? How does that impact families income? These are domino-like effects that can flow from these bad air quality situations in our neighborhoods."

Disadvantaged populations may lack access to health care, grocery stores and good jobs. Add to that the underlying chronic stress that comes with living in poverty, which researchers are finding might further increase susceptibility to conditions that include asthma, heart disease and cancer.

Poorer communities may also be more likely to encounter other environmental exposures, including contaminated water and toxic wastes. Indoor pollutants, such as cigarette smoke and cockroach droppings, are associated with both poverty and asthma as well.

“There might be multiple steps in the development of asthma. Diesel particles can encourage someone’s immune system to have an allergic response,” said Matt Perzanowski, an environmental health scientist at Columbia University and researcher on a recent study that found higher rates of childhood asthma in New York City neighborhoods that had more black carbon pollution in the air as well as a greater presence of cockroach and mouse allergens. Once a kid has asthma, Perzanowski added, such allergens may be triggers of asthma attacks.

Of course, a child living in a pest-free home on the Upper East Side, who may not have to think about where his or her next meal will come from, is not immune to air pollution's threats.

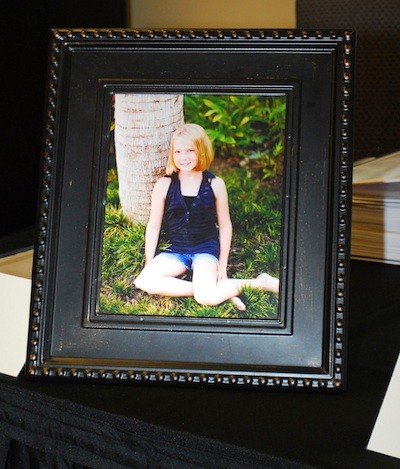

The Passons live in an affluent suburb about 20 miles north of Atlanta. The family spoke out alongside Kellen's mom at an asthma awareness event last week in Atlanta. Brennan Passons, 11, died of asthma in October.

"Brennan and Kellen are on two opposite ends of the spectrum. But it's not just one income group or demographic. Asthma affects everyone," Tim Passons, Brennan's dad, told The Huffington Post. "It naturally makes you wonder. Why is it that 10 percent of the kids in Georgia have asthma? Certainly the environment has something to do with it."

While most attention, including the American Lung Association report, focuses on ozone (smog) and particle pollution (soot), scientists are finding that specific air pollutants such as PAHs (polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons) and mercury pose a number of dangers to babies in the womb and young children -- from future obesity to cognitive problems. The pollutants tend to stem from the same sources, namely power plants, said Nolen.

The EPA has recently targeted sources of unhealthy air with new rules that restrict cross-state air pollution, strengthen mercury and air toxics standards and limit carbon emissions from coal-fired power plants. Should they withstand opposition from some members of congress and industry, 540,000 asthma attacks will be prevented each year. The proposed carbon restrictions could further decrease asthma's death toll. The biggest beneficiaries: disadvantaged groups.

The EPA and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services is increasing its focus on environmental justice issues in urban areas, as well as rural communities and Indian tribes that often fall off the radar.

"We need to target these worse-off neighborhoods," said Duke’s Paul. "By acting on pollution in places that have the highest burden, we will both be reducing the worst polluted areas and reducing disparities."

Locally, cities that include New York and Atlanta are pushing to reduce the number of idling trucks and the use of hazardous heating oils. "But the date for that to take effect is still well ahead of us," noted Corbin-Mark, referring to pending legislation that would phase-out the dirtiest heating oils from New York City buildings.

"While people are working on green answers to air pollution, which can take a long time, we don't want to wait," said Sarah Passons, who along with her husband and Rhonda Mitchell are helping to educate parents on how to protect their asthmatic children today. Sarah's recommendation: "Always have an EpiPen on you at all times, know how to use it and teach your children how to use it." An EpiPen is an injector filled with epinephrine, which relaxes airways in an allergic or asthma attack.

Kellen always knew his name would some day be "up in lights," added Rhonda Mitchell. She suggested that his dream is coming true, albeit not in a way he might have anticipated. His story is helping other kids have a better chance at a healthy life.