The Pacific Ocean is no stranger to litter, thanks to a big maritime mess known as the Great Pacific Garbage Patch. But for the past 14 months, a different type of debris has been sailing around the Pacific — not the familiar bits of plastic found in the garbage patch, but some 5 million tons of detritus that washed offshore after the deadly Japanese earthquake and tsunami of March 2011.

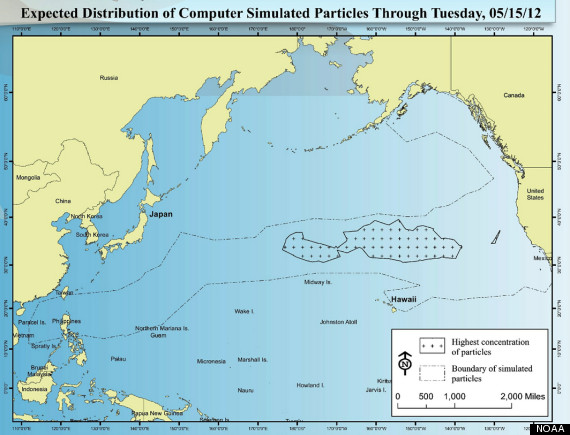

Most of that tsunami debris sank to the seabed, according to scientists at the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. But about 1.5 million tons kept floating east, and now nobody knows how much is approaching North America — not to mention what it is or when it will arrive. NOAA's computer models predict some will reach Hawaii this winter, approach the U.S. West Coast and Canada in 2013, and then circle back to Hawaii between 2014 and 2016. But as the agency points out, it's "very difficult to predict" how a mass of random objects will behave in the open ocean.

In fact, some of the debris is showing up ahead of schedule. In April 2012 alone, a Japanese teen's soccer ball washed ashore in Alaska, the U.S. Coast Guard sank a floating "ghost ship" from Hokkaido, and a motorcycle with Japanese plates emerged on a Canadian beach. According to south Alaska's Homer Tribune, "massive amounts of debris" are scattered over at least 50 miles of beaches, including wall insulation, oil and gas canisters, fishing nets and Styrofoam buoys. A new cleanup effort on nearby Montague Island aims to remove 40 tons of tsunami debris in coming weeks.

While it pales in comparison to the disaster that sent it there, some worry all this debris could pose environmental dangers for the U.S. and Canada, possibly even on par with an oil spill. "This is more hazardous than oil," Chris Pallister of the Gulf of Alaska Keeper Organization tells the Homer Tribune. "Entire communities went into the ocean — industrial, household chemicals, anything you can think of in your garage — and it's all coming here. This is like a great big toxic spill that is widely dispersed."

NOAA is more reticent in its outlook, noting that the lack of a unified "debris field" makes it hard to forecast where the objects will go. But dispersal doesn't necessarily negate the danger — NOAA warns against "picking up debris you are not well equipped and trained to handle," like sharp objects and oil drums, and adds that even lone objects can hinder ship traffic or damage coral reefs. Some items may still be clustered, too, especially if they're sealed in boxes, drums or shipping containers.

Below is a map of where NOAA thinks the debris was located as of May 15, 2012, based on computer models that consider the objects' point of origin as well as historical ocean currents and wind speeds:

Image: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

This map comes with a caveat, though: "Conditions in the ocean constantly change, and items can sink, break down and disperse across a huge area," NOAA explains. "Because it is not known what remains in the water column nor where, scientists can't determine with certainty if any debris will wash ashore."

The mystery is largely due to sparse details about the debris, since some items are inevitably more seaworthy than others. Many floating objects are considered "high-windage," with more exposed surface area that can catch the wind like a ship's sail. Soccer balls and Styrofoam fit into this category, but so do heavier objects if they're in buoyant containers. Other debris that drifts underwater or barely breaks the surface is "low-windage," and will typically take longer to cross the ocean.

Nonetheless, many people from Alaska to California say tsunami debris is already flooding in, and they want immediate action. "The time for talk is over," Sen. Mark Begich, D-Alaska, said in a recent statement. "The prospect of debris coming to our shorelines is not just a theory, it is here." Begich and other lawmakers have pushed the Obama administration to allocate emergency funds to study the tsunami debris, and to reconsider a planned budget cut for NOAA's Marine Debris Program.

"We need something much more elaborate to understand and stop this debris before it actually reaches our shores," said Sen. Maria Cantwell, D-Wash., during a May 17 oversight hearing about the tsunami debris. "Many people said we wouldn't see any of this impact until 2013 or 2014. And now ships, motorcycles and this various debris is showing up, and people want answers."

While individual objects may pose serious threats to public and environmental health, NOAA does offer one positive note: The chance of radioactive debris washing up anywhere is "highly unlikely." Much of the tsunami debris didn't come from anywhere near the damaged Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, and regardless, the nuclear crisis began after most of the objects had already washed out to sea.

The enormity and variety of the debris still makes it a threat, though, and experts emphasize it will continue washing ashore for a long time. Famed U.S. oceanographer Curtis Ebbesmeyer has said he expects the amount of debris to peak in October, and as the Associated Press reports, he told the audience at a recent tsunami symposium that about 100 vessels will likely wash up "over the next couple of years," similar to the 164-foot ghost ship sunk by the U.S. Coast Guard last month.

Yet in a reminder of how manageable such problems are compared with the tsunami itself — which killed more than 15,000 people across eastern Japan — Ebbesmeyer also offers a more somber prediction: Human bones could soon begin washing onto U.S. and Canadian beaches. "That may be the only remains that a Japanese family is ever going to have of their people that were lost," he told attendees Monday at the symposium in Port Angeles, Wash. "We're dealing with things that are of extreme sensitivity. Emotional content is just enormous. So be respectful."