Layoffs, hiring freezes and cutbacks are already starting at major medical research institutions as they face the impending across-the-board cuts to the federal budget known as sequestration. The advancement of medical cures and the careers of countless scientists are at stake.

The National Institutes of Health will be forced to reduce its spending by 5.1 percent, or about $1.6 billion this year, starting Friday if President Barack Obama and Congress don't strike a deal. Research labs in universities across America are bracing for the cuts, which they say will slow down progress on vital projects.

An accumulation of small increases, freezes and cuts over a decade is taking its toll and threatens the United States' position as the preeminent source of scientific breakthroughs, said Scott Zeger, the vice provost for research at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

"America will be a little bit less competitive. We're still going to make these discoveries ultimately. It may take a little longer, people may suffer in the meantime, but we're going to make these discoveries. It's human nature," Zeger said. "The question is, what role does America want to play in the discoveries that will define our future?"

The federal government is the chief source of financing for basic medical research, so fewer dollars leads to fewer jobs for scientists and technicians, fewer projects being completed and fewer treatments for people suffering from disease, said Teresa Woodruff, who runs a laboratory studying fertility treatments for women who undergo chemotherapy to treat cancer at Northwestern University in Chicago.

"Some of our science is going to be a little slower to get done," Woodruff said. "If we're simply filling in gaps, maybe coloring within the lines, then maybe we're not making sure that the next generation of medical breakthroughs are happening at the pace that I think we want them to happen."

So far, Woodruff has avoided laying off any of the 14 people who work for her. But, she has instituted a hiring freeze and won't be taking on any new people, she said. "My lab is a small business, and we have to keep everybody funded," said Woodruff, who receives 92 percent of her budget from NIH grants.

Some university labs have already begun layoffs, and the situation could worsen if the federal sequestration cuts take effect, said Keith Yamamoto, a scientist and the vice chancellor for research at the University of California at San Francisco. UCSF, which receives more NIH money than any other research institution and stands to lose more than $28 million, has shed a few researchers so far, he said.

"In many ways, the cuts are already with us," said Yamamoto. In anticipation of sequestration, the NIH has trimmed the size of previously approved grants by 10 percent to 20 percent, he said. Many projects that can't be put on hold while researchers seek additional money would have to be scrapped, he said.

Salaries and stipends for researchers are by far the biggest cost for a medical research lab, so that's where the pain will be felt the most, Yamamoto said. "There's just no way to escape the impact on employment."

At Johns Hopkins, Zeger said he sees the same math, and knows that the leading research institution won't be able to hold on to all of its scientists and students under sequestration.

"If you put a grant in that was going to support all 10 of your people and it's cut 10 percent, that means you have now one person who can't be supported," Zeger said. "What people are doing is they are making their labs smaller."

Alternative funding sources like nonprofit foundations and private philanthropies can't cover the losses created by NIH budget cuts, Zeger said. "There is not a well to go to if this money disappears. We're just going to do less science."

The worst-case scenario over the long-term is that promising students and young scientists will abandon the field in search of more secure employment, which would lead to less progress in the search for cures, Zeger said.

"The uncertainties around trying to be a scientist in America are growing today, and I worry that the best and brightest are going to Wall Street. They're not going to science," he said.

Universities across the U.S. are facing the same pressures, said Carrie Wolinetz, the president of United for Medical Research, a coalition of academic institutions, laboratory-equipment suppliers and drug and biotechnology interests.

United for Medical Research estimates that the NIH supports more than 400,000 jobs, and that the 5.1 percent cut could result in the elimination of more than 20,000 of them. "NIH is at the center for a very complex and economically stimulating ecosystem," Wolinetz said.

The impact may not be immediately severe if sequestration takes effect, but it would be damaging over time, Wolinetz said. "It's more equivalent to a slow bleed than it is an arterial gushing situation -- but either one will kill you in the end," she said.

Academic researchers also are dealing with years of state budget cuts and a relative decline in federal support for medical research over the last decade, said Wolinetz, who also is associate vice president for federal relations at the Association of American Universities.

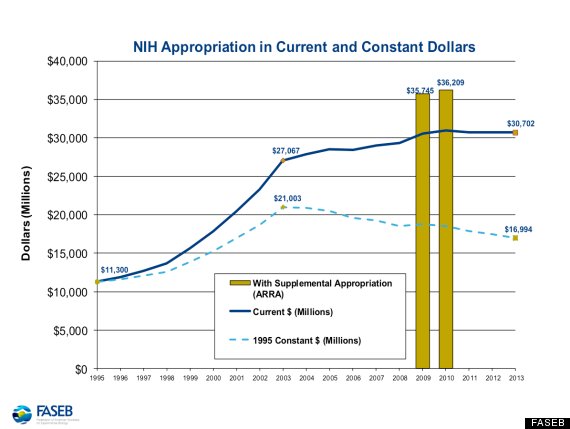

The National Institutes of Health currently has a budget that exceeds $30 billion. Between 1999 and 2003, President Bill Clinton and President George W. Bush oversaw a doubling of the agency's funding. Since then, however, NIH funding has been held nearly flat, especially when inflation is considered, except for a two-year infusion of extra money from the economic stimulus law in 2009.

The private sector won't step into the void, said Woodruff, who previously worked at Genentech, a biotechnology company.

Drug companies look for quick turnarounds on their investments in the form of treatments that can be sold to a large market -- like people with diabetes -- not basic scientific research, she said. Without federal support for her work, Woodruff doesn't believe private companies or any other funder would step to finance her efforts to prevent or treat infertility among female cancer survivors.

"It's so important for the public to understand what they're funding is innovation that wouldn't happen anyplace else," Woodruff said.