It is an old cliché: that journalism is the "first rough draft of history," the immediate attempt to contextualize events and understand their possible place in our historical memory.

It's common to look back at a story and wonder why it was given so much play, or to question how reporters could have missed something monumental happening right in front of their faces.

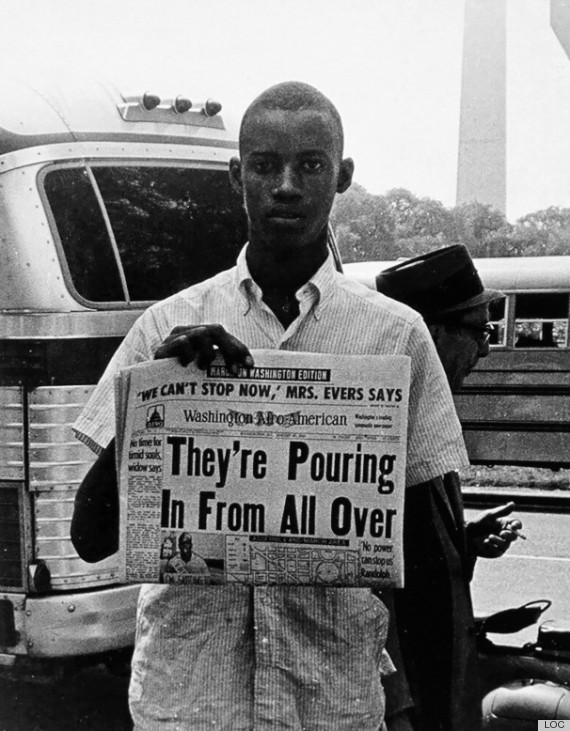

For the most part, the March on Washington was not one of those moments. People knew it was something big.

In "The Race Beat," their history of the media's coverage of the civil rights movement, Gene Roberts and Hank Klibanoff tally up the relatively vast amount of resources that newspapers and radio stations and television networks devoted to the march.

There were, they write, around 3,100 police or press passes given to journalists on the scene. The big three television networks, together with the Mutual Broadcasting radio service, sent 460 people to capture video and audio. NBC aired eleven special reports throughout the day. CBS ran the whole thing all the way through. It was broadcast live to six countries.

NBC's Frank McGee called the march part of the "American Revolution of 1963."

Visit NBCNews.com for breaking news, world news, and news about the economy

On CBS, the correspondents compared the day to a "church picnic."

NBC's Nancy Dickerson speaks to Lena Horne.

***

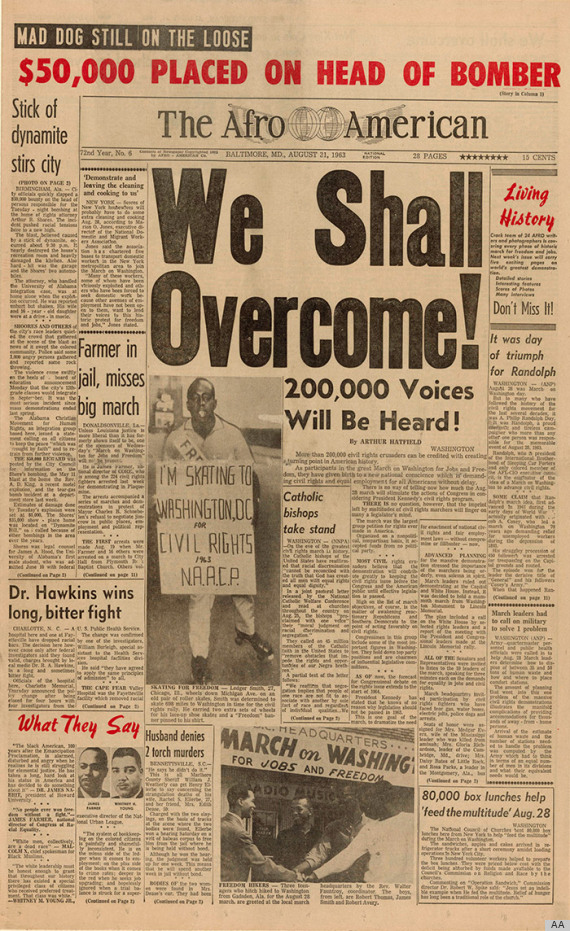

Even so, some newspapers would probably look at their front page from August 29, 1963 and cringe. Beyond the baldly racist southern newspapers, who have essentially had to apologize for the totality of their coverage of the movement, there are the northern papers who might wish they had done some things differently.

The march had to compete with the signing of a bill by President Kennedy to avert a national rail strike, and it often played second fiddle on front pages across the country.

The Chicago Tribune, for instance, would likely have had a different order of headlines in its edition than the one it came up with:

"CALL OFF RAIL STRIKE."

"Board OK's School Bias Study."

"200,000 Roar Plea for Negro Opportunity in Rights March on Washington; No Incidents"

There is no doubt that, historically speaking, the Tribune got the order wrong. The paper's editorial board also had little to say about the march. It noted briefly that "such oratory as there was, was less superheated than might have been expected."

Then, there were writers like columnist David Lawrence, who called the march a "day of public disgrace" in a piece syndicated to newspapers around the country.

"For the image of the United States presented to the world is that of a republic which had professed to believe in volunteerism rather than coercion, but which on August 28, 1963, permitted itself to be portrayed as unable to legislate 'equal rights' for its citizens except under the intimidating influence of mass demonstrations," he wrote.

History does not agree with Lawrence either.

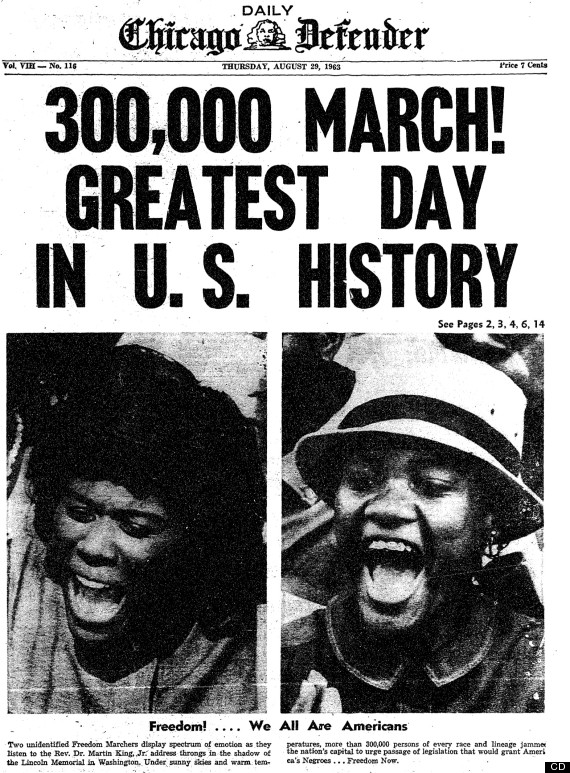

The Chicago Defender, stalwart of the black press, was probably a little closer to the mark:

***

In the past week, NBC News has been running a series of videos on YouTube. They feature everyone from Ann Curry to Chris Christie to One Direction talking about what their "dream" for the world is. (One Direction wants an end to war, hunger and bullying.)

The videos imply that Martin Luther King's "I Have A Dream" speech can be claimed by anyone, used for any purpose—cancer research, an end to financial misdeeds, political bipartisanship—and that all of this can be traced back to King's words.

Yet to look back at how the march and speech were covered is also to remember that the civil rights movement was not always a settled question; it was a living, breathing, divisive, polarizing thing, not something that people of every political stripe could embrace so easily.

White people were especially leery of the march. Most of them thought there would be riots in the streets.

"This is the day of the march for civil rights in the nation's capital and the dread specter of possible violence hangs over the proceeding," the Chicago Sun-Times wrote the day of the march.

President Kennedy didn't want the event to happen.

"8,000 Will Keep Peace at the March," an August 14th headline from the Washington Daily News read. The lede went like this: "Anyone who is thinking of coming to Washington to stir up trouble during the Aug. 28 civil rights march would be well advised to forget it."

Watching NBC's interview with King and NAACP chair Roy Wilkins from just before the march is instructive. King was hated by many, and he was, lest we forget, an unrepentantly militant activist who had been to jail not long before the march due to that activism.

Here's the first question, from journalist Lawrence Spivak: "There are a great many people who believe it will be impossible to bring 100,000 militant Negroes into Washington without incident and possibly riots."

We see the all-white, all-male group of panelists wonder whether the march is wise; whether there will be violence; whether the movement is moving too quickly.

After the march, a Baltimore Sun piece noted that just three people had been arrested, and "not one was a Negro."

The day before the march.

***

There was another thing most news outlets didn't highlight too much right away: King's speech. Longtime Washington Post staffer Robert Kaiser recently noted that his paper had virtually ignored it in the days after the march. But the Post was hardly alone.

Though the "I Have A Dream" section has become perhaps the most famous passage in American history, most media outlets either ignored it or focused on other portions of King's address. The New York Amsterdam News, for instance, praised King to the skies, but its reprint of the speech didn't even include the "I Have A Dream" section. Months later, Time magazine named King its "Man of the Year." It spent 11 pages on his life and work, and talked about his speech at the march, but didn't mention "I Have A Dream."

The full speech is angrier, more pointed, more confrontational than the vaunted section. It is centered not on talk of hopes but of bitter realities—of, as King put it, a "bad check" written by the American government to its black citizens.

According to Gary Younge, the Guardian journalist who has written a book about King's speech, the "I Have A Dream" section wasn't even supposed to be part of the remarks. It wasn't in King's prepared text. He'd made similar comments in prior addresses, and wasn't intending to make them again at the Lincoln Memorial. But then singer Mahalia Jackson exhorted him to tell the audience about his dream, and so he did.

Clarence Jones, a close adviser who helped King write the speech, told Younge in a BBC interview that he didn't think the speech would be the one King was remembered for 50 years later.

"The speech itself, as a speech, it was a good speech," he said. "But substantively, it was not necessarily his greatest speech. But something happened."

The New York Times was notably prescient about the power of the "I Have A Dream" passage, and put a story about it on its front page the day after the march. The normally hyper-establishmentarian James "Scotty" Reston was blown away:

"Dr. King brought them alive in the late afternoon with a peroration that was an anguished echo from all the old American reformers. Roger Williams calling for religious liberty, Sam Adams calling for political liberty, old man Thoreau denouncing coercion, William Lloyd Garrison demanding emancipation, and Eugene V. Debs crying for economic equality—Dr. King echoed them all."

***

There is also a danger in seeing the march as some kind of definitive hinge, a turning point that meant that America was wholly changed—and to keep King standing at that podium forever. Yet, three years later, Mike Wallace interviewed King for CBS. This was after the Civil Rights Act and Voting Rights Act had both passed Congress and been signed into law. There was King, talking about waves of angry violence that had swept through poor black communities.

"The cry of black power," he said, "is at bottom a reaction to the reluctance of white power to make the kind of changes necessary to make justice a reality for the Negro." America, he went on, "has failed to hear that the economic plight of the Negro poor has worsened over the last few years."

He then had to bat away a question from Wallace about why Jews could make it out of their "ghetto," but black people had a harder time. American Jews, he pointed out, had never been enslaved.

A year later, King would call the United States "the greatest purveyor of violence in the world today." That speech is, to say the least, less remembered than "I Have A Dream."

***

So, what are we to take from the way the media reported the March on Washington in real time 50 years ago? Mostly, it is worth being reminded that history sometimes has a way of making fools of us. A march is more important than a rail strike. A seemingly routine speech is actually an immortal one. Only a relative few thought "I Have A Dream" would matter much after the march was finished. What similar milestones have we all missed?

But the coverage also shows why it is always worth striving to push past our settled narratives of history, and to search out the complexities behind any event—both past and present.

And, of course, we should remember to be inspired by what happened on August 28th, 1963. It was a glorious day.