In the eight days ending on Friday, I took 5,940 photos of me eating cereal, getting crushed on the subway, cutting my fingernails, and checking my iPhone. I have photographed myself 523 times while writing this story. And in the time it takes you to read this, I could easily have snapped another dozen of you. Probably without you noticing.

I owe it all to my favorite new accessory: a Triscuit-sized, wearable camera called the Narrative Clip that automatically snaps a photo every 30 seconds. I’ve used the camera clipped to my clothes, strapped on my purse, fastened to a dog and propped up on my desk, where it’s watching me now through a pinhead-shaped lens in the corner of its white plastic frame. That black spot is the only vague hint it’s something more sinister than a pretty pin. From its rotating perch, my personal paparazzo has followed me to brunch, the office, dinners, two concerts, a baby shower, a television appearance, and even, by accident, to the bathroom. It stops shooting only when I slip it in my pocket.

If you’re anything like my friends, whose distaste for my surveillance binge I've captured on camera in frowns and furrowed brows, what you’re really wondering by now is, “Why?” Why be a creepy Tracking Tom who photographs strangers twice a minute? And why bother capturing such scintillating still-lives as the inside of a fridge?

Yet if you’re anything like the nearly 3,000 individuals who funded the Narrative Clip’s Kickstarter campaign, or the thousands more who’ve embraced “lifelogging” with tools like the FitBit, the appeal is obvious. Our memories are scattered, untrustworthy little things constantly misplacing important details from our lives. Computers, on the other hand, boast infinite brainpower and a knack for tracking everything we do -- one that gets better by the day. While people decry Big Brother-esque scrutiny amid disclosures of NSA spying and the spread of security cameras, the Narrative Clip taps into a related, but oddly contradictory, impulse: a zeal for subjecting ourselves to ceaseless surveillance, provided we’re in charge of the data.

The camera indulges a longstanding desire for technology-enabled total recall, an obsession that’s transforming the act of forgetting from an inevitable outcome into something that requires an active choice. Yet even more than expanding my memories, I found my own camera companion was actually creating new ones.

Martin Källström, the co-founder of Narrative, says his own glitchy cerebral cortex inspired the mini-camera. While birthdays and holidays are photographed (and thus remembered) in copious detail, he was distressed by how quickly the mundane events of everyday life, like breakfast with his kids, slipped from memory. He wanted something capable of “gathering as much data as possible” in a way that was “very, very effortless,” Källström told me in a 2012 interview. And thus was born the Narrative Clip, which claims to satisfy “the dream of a photographic memory.”

“Sadly, I’ve lost both my parents, and I really feel that the time I spent with them is fading, and the memories of them are fading much more quickly than I’d like them to,” Källström said. “What is left are the stories that we have always told each other … and the photos that have ended up in albums. The in-betweens are getting lost more and more.”

The early computer pioneer Vannevar Bush shared a similar concern. In his influential 1945 essay “As We May Think,” Bush made a case for augmenting the human mind by creating an all-remembering storage device Bush dubbed the “memex.” A person would create this “enlarged intimate supplement to his memory” by feeding it books, letters, records and the images captured by an unusual camera. Bush predicted the “camera hound of the future” would supplement memory by attaching to his forehead a camera only “a little larger than a walnut.” He was off only by the size: Narrative Clip is smaller than a walnut, though its creators do suggest strapping it to a headband. (This isn’t fantastic news for anyone who cares about their privacy. Like Google Glass, the Narrative Clip also enables stranger-on-stranger surveillance that, short of banning the technology or strictly limiting its uses, could be impossible to suppress as the device's popularity grows.)

At the end of a week, my Narrative Clip had assembled a photographic “memex” that offers the closest thing yet to a time machine. The Narrative app divvies my photos into albums that transport me to a specific time -- my car ride Saturday, Feb. 1 at 12:46 p.m., for example -- for a taste of who I was and what I was doing at that precise moment in the past. None of my Clip snaps have made it to Instagram, nor have I bothered to weed out the bad ones. The pleasure, as Källström envisioned, comes from replaying a stop-action animation of an unremarkable, totally average day. Looking through my albums, the only remarkable thing that emerges is how much I’d give to see the same kind of photos taken during an average day when I was 4, or 16, or even 26.

But then there were the things I couldn’t place, like the bizarre looks from unknown individuals, or the bookshelf in my apartment that, seen from a new angle, suddenly looked sadly shabby.

The Narrative Clip didn’t just let me “relive life’s special and everyday moments,” as the ad copy on the camera’s sleek box had promised. When I scrolled through the thousands of photos it captured, I had the feeling of discovering entirely new dimensions to an experience I thought I knew. It both jogged my memory and fiddled with it.

I’m crushed to discover someone sneering at me as I passed by her, leaving me obsessed trying to explain this mystery enemy I ticked off for unknown reasons. A picture of me gesticulating while I chat with a friend caught him looking miffed at our conversation. But since the Narrative can only tell me that we were talking -- not what we were talking about -- I can’t remember if I said something that might have irked him. Should I apologize? For what? Was it an awkward remark, or just the shutter's awkward timing? And then there’s watching my bad habits replayed over and over and over during the hundreds of photos during my workday -- the nibbling, the lip-biting, the squinting, the snacking. Cruel and unusual punishment indeed.

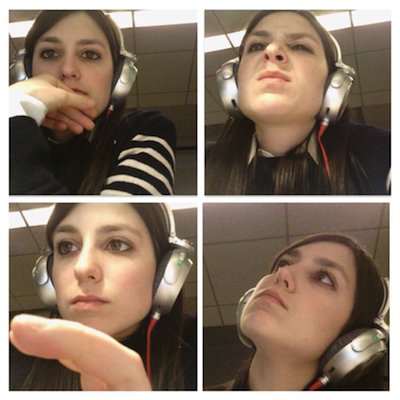

The Narrative Clip captures the author at work.

The Narrative Clip captures the author at work.

The Narrative Clip lets me see my life through someone else's eyes -- or in this case, the unfocused and impartial eye of a machine. Its blunt record can expose our faults. As Bush wrote, “Presumably man's spirit should be elevated if he can better review his shady past and analyze more completely and objectively his present problems."

And yet, as any historian knows, reconstructing our past requires interpretation along with the facts. Even if an all-capturing camera provides us with a photo documentary of our lives, we still get final say when inventing the story that goes with it. That picture of my friend, for instance. I just remembered what was happening: He was taken aback by the brilliant, inspired and utterly earth-shattering observation I'd made that same moment.

At least the picture doesn't say otherwise.