You probably don't know who makes your clothes. The scary thing is, the retailer that sold them to you may not know, either.

A yearlong study of factories in Bangladesh by New York University's Center for Business and Human Rights found that many retailers can't be sure which factories make the products they sell, often in immaculate shops half a world away. That's because manufacturers sometimes farm out work to local factories that aren't registered with trade associations or the local government and that operate away from the eyes of regulators, the study found.

That means many retailers are just as in the dark as shoppers about whether a piece of clothing was stitched together by workers earning rock-bottom wages in some of the world's most decrepit, ramshackle factories. Or whether it was made with child labor. Or if workers sewed under sickening working conditions. Or if there are cracks in the factory's walls that could trigger a catastrophe like the collapse of the Rana Plaza factory complex in Bangladesh, which killed more than 1,100 people last April.

"We're hiding," the owner of a tiny unregistered factory in Bangladesh, the world's second-largest exporter of ready-made garments, told investigators. "Those customers won't like my factory because it's a tin shed."

The owner in question employs 110 laborers who spend their days jammed into a little concrete edifice in front of the owner's house, surrounded by heaps of fabric as they sew together pants. The finished clothes carry the label of an unnamed "major European brand," according to the report. The factory is one of up to 2,000 unregistered garment facilities in Bangladesh that dodge government oversight.

When retailers place orders for clothes, production doesn't always go smoothly. Factories end up pressed to get their shipments out on time, or risk losing future jobs. Rather than opening extra lines at the factory, forcing workers to work extra hours or trying to negotiate a later delivery date, garment-makers can agree to have the goods made in another factory -- a process called subcontracting.

Most big retail brands have strict policies against unauthorized subcontracting. There's much at stake for them, including quality control, efficiency and the risk of public-relations disasters.

Factories are supposed to ask the buyer if they can subcontract a piece of the original order. The retail brand would have to send inspectors to the subcontractor to make sure minimum safety standards are being met, then authorize the decision.

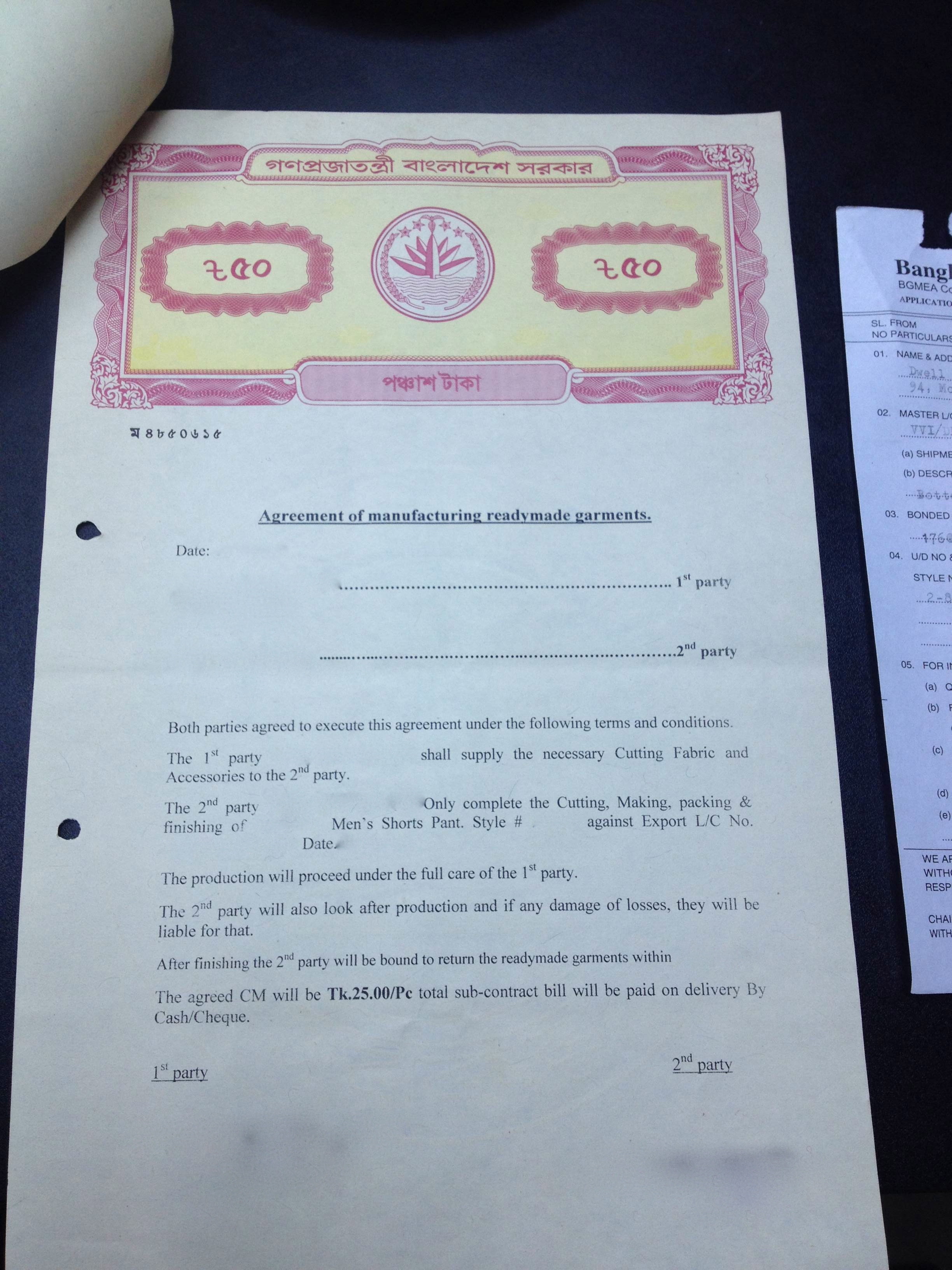

But this doesn't always happen. More commonly, the NYU report found, factories don't tell retailers that they've subcontracted an order. Instead, they go through one of the country's trade associations and register what's called an "interbond license." Then the pair of factories sign a short contract defining the price, quantity and delivery date of the order.

In one contract shared with investigators, there was no mention of labor compliance:

Such subcontractors often delve into a grimier tier of factories far outside the reach of any regulatory systems put in place by the government.

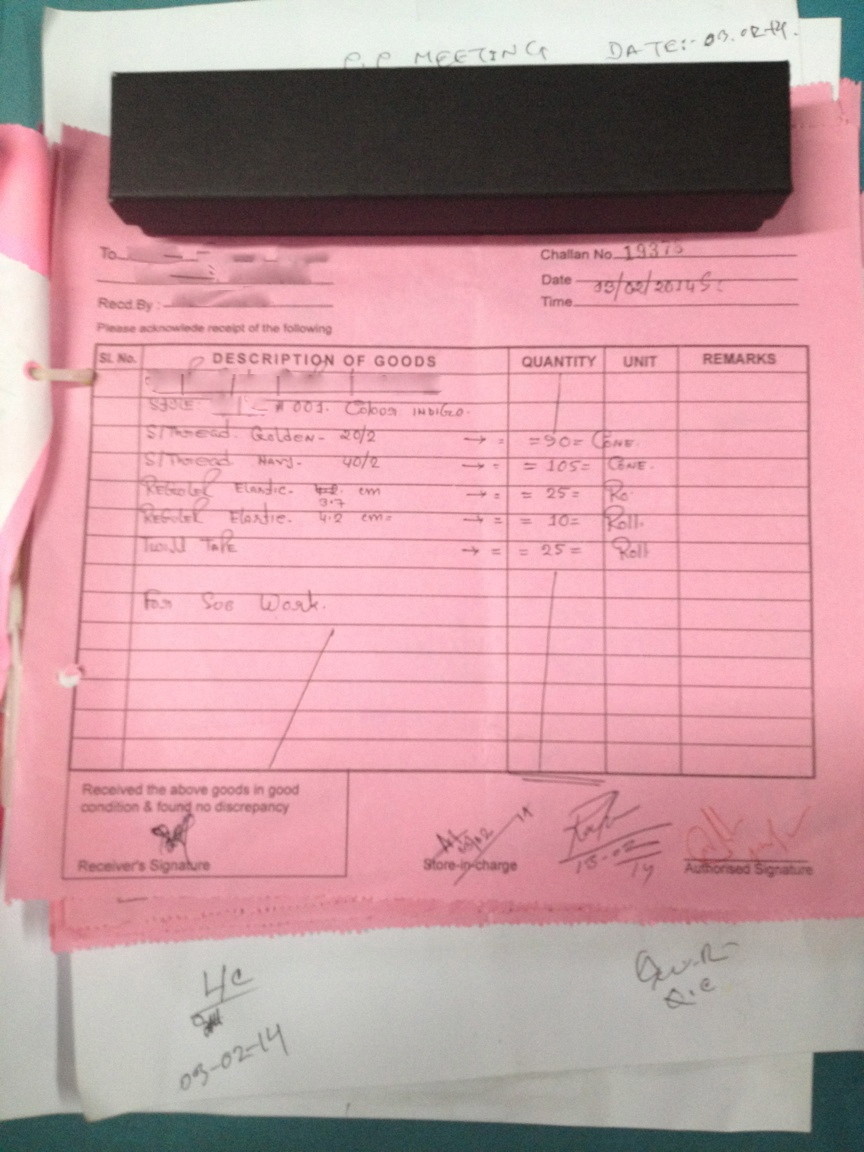

At this level, the subcontractors use a system of informal handshake agreements. Factory managers simply call a friend who runs an unregistered operation, and they agree to terms verbally. Then, it's a simple system of bills and receipts where cash is exchanged for garments.

Investigators acquired this receipt, which lists all the materials delivered for such an order:

Since suppliers don't report these deals, and there's not much of a paper trail, retailers may never know where their own clothes were actually made.

Retailers and regulators have done little to snuff out such side deals. Despite efforts from the international community to improve the garment industry in Bangladesh, it remains broken, more than a year after the Rana Plaza tragedy.

Coalitions of global retailers, including juggernauts like H&M and Gap, have struck two separate agreements to address broad concerns about factory safety: the Bangladesh Accord on Fire and Building Safety and the Alliance for Bangladesh Worker Safety. They have set stricter standards and scheduled more frequent workplace inspections. But inspectors keep finding widespread problems in factories.

The NYU report calls for companies to figure out how far their webs of subcontracted factories go. The Bangladeshi government has yet to agree to list the factories that make clothes for each brand, and retailers have yet to do the same. Even that step would only, at best, solve the problem of knowing where the clothes come from. It would still leave a long struggle ahead to upgrade working conditions throughout the country's garment industry.

Otherwise, there has only been "empty rhetoric" from companies and governments about cracking down on these shady practices, the report says.