At the beginning of 2014, Stanford University senior Leah Francis awoke at a fellow student's house during winter break to find him sexually assaulting her, pinning her down with his body weight.

The following week, after suffering from "massive" panic attacks leading to three nights in a row in the emergency room, Francis reported her assault to police. When she returned to the Bay Area campus, Francis also reported the attack to the university and pursued adjudication through what's known as the Alternative Review Process, a board consisting of students and staff trained to handle sexual assault cases.

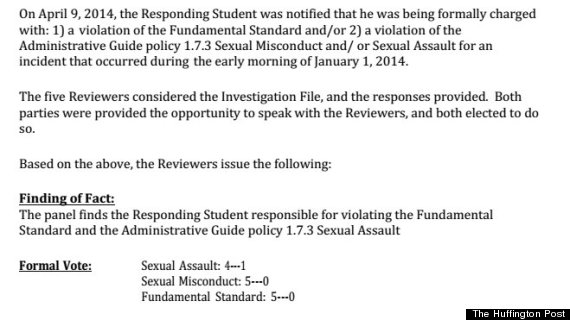

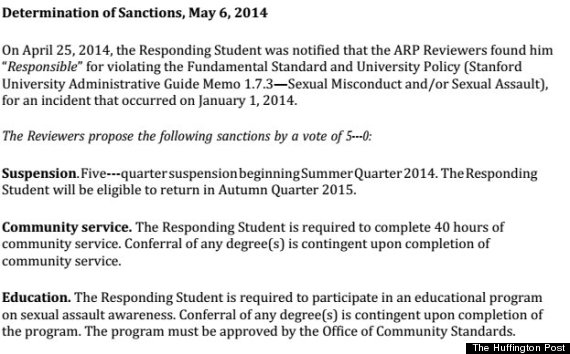

On April 24, Francis had a verdict from the ARP: The accused male student was found responsible for sexual misconduct and sexual assault using force. On May 6, she was informed the assailant would be punished with a five-quarter suspension, community service and a requirement to take a class about sexual assault. However, the suspension wouldn't begin until after commencement in June, when the accused student would receive his diploma. Francis sees it as essentially a forced "gap year" for her perpetrator before he can begin graduate school at Stanford, to which he is already accepted.

Meanwhile, Francis will graduate late, due to a reduced course load she took this year while recovering from anxiety she experienced as a result of the assault.

"When I would see him around campus, it would end the day for me right there," Francis said. "I would just be panicky."

Stanford spokeswoman Lisa Lapin noted that interim accommodations are offered to reporting victims while they go through adjudication.

"The university works with the impacted party to determine what would be most appropriate," Lapin said. "Throughout the process, the university adjusts interim measures as needed to assure the safety of the impacted party and the larger Stanford community."

However, Francis said her assailant violated a no-contact order during this time, showing up at both her house and classroom. A day after the sanction was decided by the school, an unidentified male also burst into Francis' room in the co-op where she lives, Francis said, shouting "Don't you think he would be off the campus by now if he'd actually done it?!"

The incident was reported to Stanford, and the male intruder has not been identified.

"We do regret any circumstance in which a student believes a process here at Stanford has not met their expectations," Lapin said. "We take very seriously the pain and trauma that are generated by sexual assault."

Francis led a campus demonstration Thursday to call attention to what she sees as an inappropriate punishment for a student the university decided was responsible for sexual assault.

(SEE PHOTOS OF THE DEMONSTRATION BELOW)

According to information obtained by The Huffington Post, nine Stanford students have been found responsible for sexual assault since 2005. Only one of them was expelled, and he was determined to be involved in multiple cases. Between 1997 and 2005, no students at the school were found responsible for sexual assault.

Suspensions for eight other cases where a student was found responsible for sexual assault ranged from one quarter to eight quarters.

Documents given to Francis by the university said the ARP panel based their sanction on precedent.

Since the university has only expelled one student for sexual assault in school history, basing an adjudication on precedent is bad policy, said Stanford law professor Michele Landis Dauber, former co-chair of the Board on Judicial Affairs overseeing campus adjudications.

Typically, the board has suspended assailants until the victim is no longer on campus, Dauber said. The problem is that "if you rape a freshmen, that's a long suspension," Dauber explained, "and if you rape a senior you might be getting away with something."

Dauber added that when school authorities hand out relatively brief sanctions to assailants, it can discourage other women from reporting their own assaults.

"Women are telling their friends, 'Don't bother -- if you get all the way to the end [of the adjudication process], nothing really happens,'" Dauber said. "It's very bad for the university because now there's tremendous publicity around the fact. It's bad in the sense that young women will undoubtedly hear in the short term our process is bad, and will not want to participate in it, which is bad for campus safety."

There is no national standard for sexual assault expulsions, and colleges often choose not to disclose what sanctions they use.

From 2008 to 2013 at the University of California, Berkeley, for example, the flagship institution found 38 students responsible for sexual misconduct, and it expelled or suspended nine, according to information provided to HuffPost.

UC Berkeley declined to say exactly how many students were expelled, saying "the numbers would be small enough to be identifying." However, no one has been expelled since 2011.

A few of Stanford's peer institutions, including Dartmouth College, Yale University and Brown University, release annual or semi-annual reports about how many students have been expelled or suspended for sexual assaults.

Between 2010 and 2013 at Dartmouth, the school removed two students for sexual violence, suspended two others and placed two more on probation. Brown expelled two students for sexual misconduct in the 2012-13 academic year, and suspended two others.

Since fall 2008, Harvard University has dismissed a total of five undergraduates for "social behavior - sexual," according to a report prepared by the school. Two others were placed on probation for "social behavior - harassment/sexual."

Dauber advocates for expulsion in cases of sexual assault, given that most campus rapes are committed by serial offenders, according to research from the psychologist David Lisak.

Students involved in organizing Thursday's protest at Stanford want the school to make expulsion the preferred sanction, as Dartmouth and Duke University have done.

From The ARP Letter Delivered To Leah Francis And Her Assailant:

CLARIFICATION: This article previously identified Amherst College as making expulsion the preferred sanction for sexual assault, which was one of the schools student protesters cited as an example. Amherst has not made expulsion the preferred sanction, only that it remains an option the college may chose in sexual violence cases.