No form of communication has been as maligned as the emoticon. Emily Post's decorum police thumb their noses at smileys' grins. "[T]hey look juvenile in business," the etiquette gods caution. "[A]void using them." The distaste for emoticons is almost as old as the world wide web itself: In 1994, a Seattle Times columnist demanded an outright ban on emoticons. He declared them the "smallpox of the Internet."

But the typed smiley, which has kept a brave face throughout, doesn't deserve its dismal reputation. Though emoticons haven't yet shed their stigma as the taboo tell of the unsophisticated luddite, evidence from a decade of academic research suggests we should be emoticon-ing with greater abandon (an exciting piece of news given the new emoji arriving soon). Using ":-)" can win over friends, make you likable and even boost your mood, researchers have found.

At the Conference on Weblogs and Social Media this month, a group of computer scientists proved that embracing emoticons is the eighth habit of highly successful people. Simo Tchokni of the University of Cambridge Computer Laboratory analyzed over 31 million tweets and half a million Facebook posts to catalog our linguistic status symbols, the textual quirks that differentiate posts by social media's prestigious few from the musings of the masses. The humble emoticon distinguished itself as one of these status markers -- the online equivalent of the personal assistant.

"Individuals who use emoticons often (and positive emoticons in particular) tend to be popular or influential on Twitter," Tchokni and her colleagues concluded. Forget dressing for the job you want: type emoticons for the status you crave. A ":-)" here or there might not change your stature overnight. But like having a firm handshake at the office, mimicking the social media elite could be a first step to landing in their ranks.

Other studies reveal that emoticons can either temper or boost the emotional punch of what we write, suggesting they're not extraneous flourishes in a message, but helpful cues that clarify what we mean to say. Sad messages seem sadder with a :( and cheery messages seem cheerier with a :), according to a 2007 experiment. In fact, the simple combination of a colon, parenthesis and dash is a closer stand-in for a smile than you might realize: A study published this year determined our brains process emoticons and human faces in much the same way.

A strategic ":-)" can also take the edge off, which may help bypass the "reading rage" that can erupt over a poorly phrased email. Last year, a trio of graduate students at the Florida Institute of Technology recruited over 100 computer-savvy working professionals to consider two hypothetical messages:

I can't make the meeting you scheduled because it conflicts with my staff meeting. Email me and let me know what I missed.

and

I can't make the meeting you scheduled because it conflicts with my staff meeting. Email me and let me know what I missed. :-)

Adding a smile lessened the sting of what otherwise seemed like a more negative command, the study's participants reported. Far from branding emoticons an infectious disease, the Florida team endorsed them as a handy tool that could "help mitigate cyber aggression and the resulting escalation of conflict" by "clarifying messages and giving the conversation a more 'light-hearted' tone."

![]()

While people in the Florida study considered emoticon-embracers less professional, there's solid proof emoticons can both sweeten your words and make you more delightful. A 2010 experiment found that when individuals received written criticism from a colleague who used emoticons, they thought the person had better intentions than someone who'd omitted the smiley faces. In another investigation, a professor had participants chat online with health experts and film buffs who alternately used or avoided emoticons. The readers who received smiles in their chats considered their conversational partners friendlier and more competent than the insensitive jerks that ditched the emoticons.

Counter to almost every instinct we have, smiley faces even belong in our business missives. To explore how people react to the smiley symbol when it pops up between friends versus employees, Jina H. Yoo, a communications professor at the University of Missouri-St. Louis, created two Photoshopped messages: one that appeared to be an email from a firm extending a job interview request, and one that looked like a flirtatious note from a stranger on an online dating site. Some versions featured emoticons, some did not.

Seeing smiley faces in the fictional business email made readers trust the sender less, Yoo found. However, regardless of whether it was a work email or a love letter, participants who saw emoticons reported liking the sender more and feeling the sender liked them more. The readers also expressed more affection for the senders who used emoticons.

![]()

What gives? Why do we hate emoticons, but love the people who use them?

The surprise of seeing a smiley face in buttoned-up business correspondence can create a "positive expectancy violation" -- an act that defies our predictions, but in a way that intrigues or delights us. In this sense, the emoticon's juvenile associations may actually work in its favor: Yoo hypothesizes that in the sterile context of a work email, where formality is touted as a way to build professionalism, receiving an emoticon is an unexpected, but welcome, "friendly, emotional and personal" act.

But there's also the issue of who's receiving the emoticons, and how many they get. Many of the studies tracked how students -- a smartphone-toting, text-speak-typing cohort of digital natives -- responded to the smiley faces. Their tech fluency might make them more disposed to :-)s. A 2004 article on the "generational approach" to using emoticons concluded that millennials "may be sent e-mail with generous use of emoticon," but that their elders would not be so tolerant. (Two emoticons per email induced the greatest warmth in the recipient, Yoo found.)

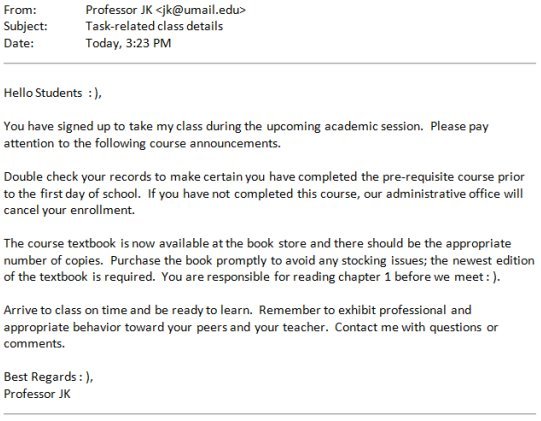

A 2013 Master's Thesis found students positively regarded teachers who included a few emoticons -- more than one, fewer than seven -- in their emails (See model letter above). "[T]eachers may utilize three emoticons to improve perceptions of caring with little chance to harm credibility and liking," the study's author wrote.

But ten years on, those biases seem weaker than ever, even among the more elderly texters. Our writing online has become more informal and prolific, and the emoticon has in turn grown more useful and increasingly ubiquitous. Since the Seattle Times' screed, we've taken up messaging each other on dozens of new forums: Facebook, Tumblr, Tinder and Twitter. In comments sections, in chat rooms. Via email, over Skype. There was a day when "electronic mail" was something official we wrote sitting in an office. Now, it's a casual note we dispatch from the back of a cab, one in which the more chilled-out grin of an emoticon fits just fine. The smiling images have snuck into more of our missives to each other, and we're no longer surprised to see them there.

"Back in day, we used to use an emoticon mostly when corresponding via email. But now, the nature of communication has changed," said Sriram Kalyanaraman, a journalism professor at the University of Florida who focuses on the psychology of new technology. As a result, he added, "the language of communication has changed" and emoticons have "gone into the mass culture."

We're not only accustomed to emoticons, but we've also realized how much we need them. We've had enough awkward miscommunications to know that looking like an email rube is better than being vague and risking ill-will. The rise of emoji -- emoticons' more expressive and colorful cousins -- offers proof that we haven't outgrown the need to sprinkle our prose with faces and emotional cues. The good news is, instead of grimacing when we use a smiley, we should feel good about it.

And science says we will: People who use emoticons, a 2008 study found, experience a "positive effect on enjoyment, personal interaction, perceived information richness, and perceived usefulness." That's something to :-) about.