“Every artist is concerned with these questions, of who we are and where we are going,” says Prune Nourry, pulling her long brown hair away from her face. The gesture is impatient, and you can see why: Nourry is the artist behind "Terracotta Daughters," an ambitious, multi-year project that involves carting 108 life-size sculptures around the world before finally burying them in China.

It’s a task that demands stamina, and an intolerance for such distractions as hair in the face. On display through the end of the week at the China Institute in Lower Manhattan, the installation recalls China’s famed Terracotta warriors, which were buried in the soil of Xi'an and discovered centuries later. Only instead of thousands of clay male soldiers, Nourry’s army is made up of statues of girls.

Born in France, Nourry has found her inspiration in the world’s most populous countries. A previous project took her to India, where she made hybrid sculptures of cows mixed with girls, to explore the country’s conflicted attitude toward women. Now she is questioning the Chinese paradigm of gender selection, by trotting around the likenesses of girls to be feted worldwide in a manner befitting the original Terracotta warriors.

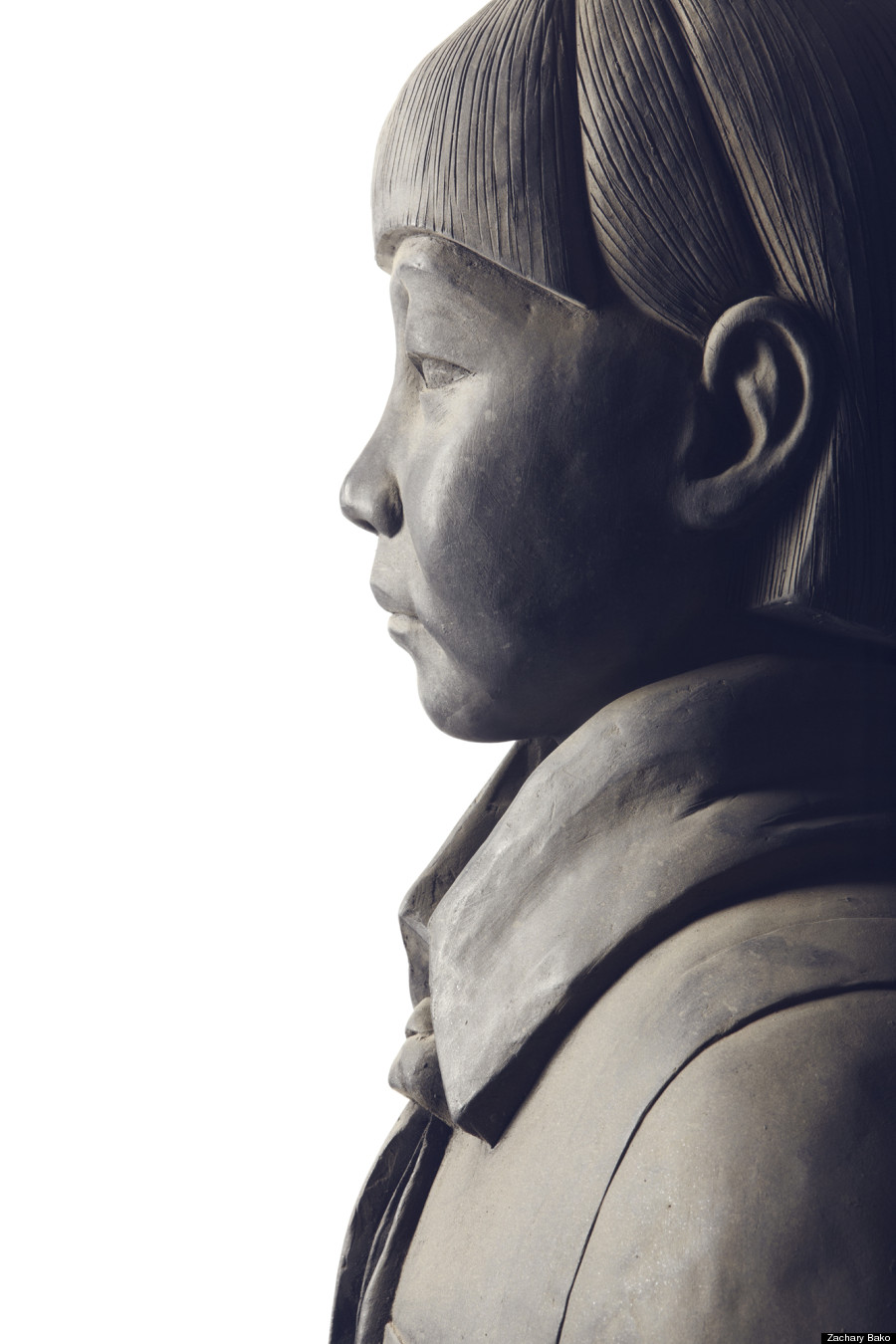

The schoolgirl-ish ponytails and neckties didn’t come from thin air. The templates were eight original molds sculpted by Nourry, which she based on photographs she took of actual girls, orphans between the ages of 10 through 13, selected by the nonprofit agency The Children of Madaifu. The idea was to generate a contribution through the Daughters projects. Proceeds from the sale of these molds and various bronze versions went to fund Nourry's army, and three years of education for all of the girls.

Nourry chose to work near the site of the Terracotta warriors' burial, where the production of knockoff warriors has become a cottage industry. She enlisted help from the craftsman of a particularly beautiful factory located a few miles from where the girls live. The site struck her both for the quality of the light streaming in (she filmed the project as it was carried out), and a sense that, once inside, you could be in any era.

Rows of identical clay soldiers lent a futuristic quality to a scene that was otherwise old world, “more like a workshop than a factory,” she says, with busted windows through which plants crept. She compares the fecund atmosphere to that of Angkor Wat, the great overgrown temple in Cambodia. Additionally, she loved what she calls the “charisma” of the craftsmen’s faces and gestures.

The project wasn’t an easy sell. “I was French, young, foreign, a woman, didn’t speak the language. And here I had this monumental idea,” she says. The craftsmen disagreed with the base logic of the enterprise. “We don’t believe her imagination,” says one, Xian Feng, in a 20-minute film accompanying the China Institute installation. “Terracotta soldiers are warriors, and in the army it’s impossible to see girls.” To deny that reality, Feng says, “didn’t feel right to my hands.”

As he fell deeper into the project that feeling lessened. Nourry tasked Feng, a master craftsman who she calls the “column of the studio,” with developing unique faces for each girl. Initially he felt uninspired, but soon realized he had all he needed at the local school gate. He began to keep an eye out for interesting features and hairstyles. “At that time I was completely absorbed,” he says.

Nourry says part of the project was to simply change the minds of the craftsmen, many of whom experience the effects of gender selection in their homes. (Feng, for instance, calls his family “basically all boys.”) To further individualize the soldiers, Nourry had the original molds sliced into horizontal pieces: torso, head, legs. These were used as templates that could be swapped into a variety of combinations, so no two girls are alike.

Their last stop is China, where Nourry will commence what she calls a “complex” burial project next year. The warriors are scheduled to be unearthed in 2030, the year China’s gender imbalance is predicted to peak. Such a prospect is bleak, but Feng might say that rarity makes something precious. One of his more profound asides in the film is also one of the most surprising. “I like boys, but I like girls better,” he says with a smile. “In general, my family has too many boys. So that’s why.”

Terracotta Daughters is co-presented by the French Institute Alliance Française (FIAF) and China Institute as part of FIAF’s Crossing the Line festival.