While the number of children medicated for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) continues to rise, a new study shows that the number of kids who actually take such medication varies by season.

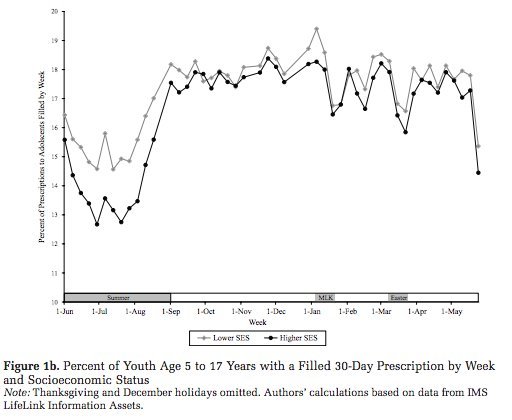

According to research published this month in the American Sociological Review, middle and high school students are 30 percent more likely to have a prescription filled for stimulant medication during the school year than they are during the summer. However, these rates aren't uniform across class or location. Students from higher-income families, and students who live in states whose governments more closely monitor school performance, are more likely to only take medication when school is in session.

Researchers also found that the trend was more pronounced among families with private insurance than those with public insurance. Using this indicator, researchers concluded that wealthier children were going off medication during the summer at a higher rate than less wealthy children, as public insurance programs like Medicaid serve families with limited resources.

Notably, ADHD is associated with a number of attributes that could be detrimental in school settings, such as forgetfulness and inattention. For those reasons, the study notes, stimulant medication like Adderall or Ritalin can help improve academic performance for students both with and without ADHD.

Researchers also found that students were more likely to go off their stimulant medication during the summer months in states with strong educational accountability systems. The report measured those accountability systems based on state ratings from Education Week Research Center's 2008 Quality Counts report, which looked at factors like how strongly states hold schools responsible for their performance.

The study's authors ultimately conclude that wealthier students are more often taking stimulants during the school year in response to academic pressure.

Jennifer L. Jennings, an assistant professor of sociology at New York University and a co-author of the study, told The Huffington Post that the study's findings could be interpreted in a number of ways.

"If it's the case that kids only need their medication during school, perhaps we should look at what's happening at school as opposed to the kid. Largely that's the way we're thinking about it," said Jennings. "Another way to look at it would be, 'Actually, these kids need to be on these medicines continuously. Doctors and parents are doing these kids a disservice.'"

She continued, "If you think the true rate [of kids who need to be medicated for ADHD] is probably the summer rate, you should think about changing schools, as opposed to kids."

Marissa King, an assistant professor of organizational behavior at the Yale School of Management and another co-author of the study, suggested to USA Today this week that schools have become "more academic," meaning they now place less emphasis on subjects like arts and physical education, and more emphasis on reading, math and other subjects that can be assessed with standardized testing -- a wide-reaching trend that research has attributed to the 2002 adoption of the No Child Left Behind Act.

"As schools become more academic, as a consequence we're seeing an increase in school-based stimulant use," King told USA Today. "Kids are actually just trying to manage a much broader shift in the way the school day is structured."

Laurence Steinberg, a professor of psychology at Temple University and author of Age of Opportunity: Lessons From the New Science of Adolescence, told HuffPost that the study illustrated "another weapon of higher-SES [socioeconomic status] families to manage their kids' school performance and school careers."

"What we can't tell from the paper is whether the results are saying that higher-SES parents have more concern about side effects of the medication, or that they take their kids off medication when they perceive them as not needing it," Steinberg went on. "Or both."

He agreed that the results suggest that schools in states with higher accountability standards create abnormally high-pressure environments.

Michael Petrilli, president of the Thomas B. Fordham Institute, an education think tank, took issue with that interpretation in an interview with USA Today. He told the newspaper that he thinks "schools look the same from state to state and city to city."

"Affluent kids and their families are worried about the SAT -- they're worried about getting into elite colleges," Petrilli told USA Today. "They're not worried about passing the state test."