With its new mobile payment feature, Apple promises to make something that is already pretty easy -- spending money -- even easier. While that's great for Apple and retail partners like McDonald's and Walgreen's, the benefit to you is debatable.

When it's easier to spend money, most research finds, people simply spend more money. Like credit cards and debit cards before it, Apple Pay is another step closer to the salesperson's dream: shoppers who think less and spend more.

Apple Pay, which debuted on Monday, is built into the iPhone 6 and 6 Plus, and lets you pay for stuff by tapping your phone on a reader at a handful of participating retailers. (The technology is called Near Field Communication, or NFC).

On its site, Apple calls its system “contactless,” promising it will eliminate the “wasted moments finding the right card."

It’s unclear if those wasted moments are, as Apple implies, annoyances anyone really would like to banish from their lives. Certainly, they are small impediments to buying that companies would like removed.

And it's not just fumbling for a card that Apple wants to eliminate. When you look closely at Apple Pay's retail partners, it becomes clear that the company isn't trying to replace credit and debit cards. It's going after cash, and the limitations paper money puts on spending.

“You go into a restaurant and you want a latte, and then you decide you want a latte and a muffin. But you’ve only got three dollars on you. You’re going to just get the latte,” Helaine Olen, a journalist and author of Pound Foolish, a book about the failings of the personal-finance industry, told The Huffington Post.

If you're using a card or, now Apple Pay, you buy the muffin. And the restaurant wins more of your money.

The daily muffin transactions are exactly where there’s an opportunity to replace cash. Whole sectors stand to benefit from its disappearance.

We've known for a while that, when people spend with credit cards, they spend more. Researchers call this "decoupling" -- separating spending from thinking. The more frictionless spending is, the more we spend. The New York Times’ Ron Lieber recently resurfaced a 2001 MIT study that found subjects were willing to pay between 60 and 115 percent more for the same item when paying with a credit card. The researchers called this “the credit card premium.”

“When you don’t have cash, you spend more money,” Olen said. This effect is also seen with debit cards, even though those are directly tied to the finite value of cash in consumers' bank accounts, Olen noted.

Disguising cash payments as something else is the key. For instance, a study 2008 study by NYU and University of Maryland professors titled Monopoly Money concluded that “the more transparent the payment outflow, the greater the aversion to spending, or higher the ‘pain of paying.'"

"Less transparent payment forms tend to be treated like [play] money and are hence more easily spent," the study added.

In other words, the twinge we feel when handing over piles of green paper really is a constraint on spending. That's why it makes sense for Apple to try to replace cash payments. Based on American payment habits and Apple Pay's partners, it's clear that's exactly what Apple is doing.

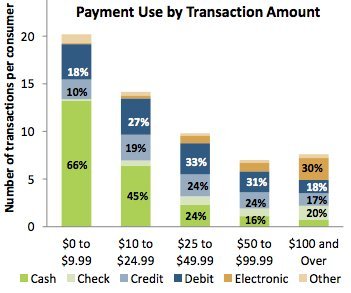

It’s easy to think of cash as antiquated, but a report from the San Francisco Fed showed that cash still dominates low-value, high-volume purchases. Sixty-six percent of transactions worth less than $10 are done with cash, according to the study. The biggest opportunity for Apple Pay, it turns out, is in replacing cash, not displacing plastic.

Above $10, cash’s prominence fades, but is still strong. Cash is used in half of all transactions of less than $50, according to the San Francisco Fed. Above $100, electronic payments and checks become a bigger force because they're used to pay bills.

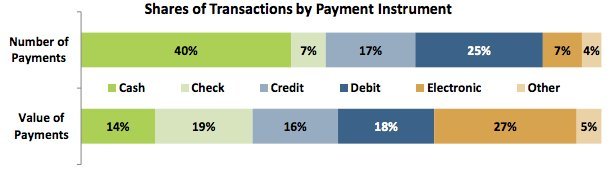

This distribution creates a funny phenomenon: Cash makes up a big portion of total transactions, but a much smaller portion of the total value of those transactions.

Displacing cards' role in American consumption habits is difficult, because cards are convenient. It makes sense, then, for Apple Pay to try target small transactions, where the data shows Americans are still using cash a lot of the time.

And the list of Apple Pay partners announced so far is dominated by merchants who specialize in high-volume, low-price transactions: Subway, McDonald’s, Panera, Walgreen’s, Duane Reade, Chevron, Texaco, and a whole host of national but not high-end retailers like Macy’s and Toys R Us. (Starbucks is technically in, too, but not really. Starbucks' cash registers don’t have NFC technology, so you will only be able to use Apple Pay’s in-app payment system to reload Starbucks cards.)

To date, just 6 percent of U.S. adults have paid for something in a store by scanning their phone, according to Business Insider research. But things that are very small can grow very quickly, and Apple has a history of successfully reorganizing consumer behavior. The same report predicts mobile payments will grow at a compound annual rate of 154 percent in the next four years.

Apple has competition, of course. Amazon wants to turn your phone into a barcode scanner. Slate’s Ariel Bogle writes that this will allow consumers to take whatever is in their hand, and “immediately buy it on Amazon. Which, of course, will have her payment information conveniently stored.” And then there are the banks and other financial institutions. JP Morgan is participating in Apple Pay, but it’s also developing its own payment app. (CEO Jamie Dimon accurately if inartfully described the bank’s mobile payments strategy: “We’re going to be in other people’s wallets.”) Bogle and Businessweek’s Kyle Stock rightly conclude that the frictionless spontaneity Apple, Amazon, JP Morgan, and other banks are pushing moves consumers further down the continuum of what behavioral economists call decoupling -- the process by which decisions about money are separate from thinking about money.

Credit cards, debit cards, one-click shipping, in-game purchases, and iTunes buying all partially and momentarily displace money as a barrier to buying.

If Pay is successful, Apple will be in a strong bargaining position to demand a cut of the purchases flowing through its phones. Recode’s Liz Gannes showed that there is money in moving desire and purchase closer together. If businesses are making more money because of Pay, they are going to find it hard to say no when Cupertino asks for its cut.