Raising a black son, Gail Howard couldn't shake the fear that someday, he was going to get shot. She even saw a therapist, who told her the odds were higher that she'd win the lottery. Jordan, an A student and an athlete, wanted her to relax, too -- he told her she treated him like a baby. The 17-year-old spent the entire day of Jan. 5, 2011, begging his mother for permission to walk alone to meet up with friends. Eventually, she grudgingly gave in.

"I said, 'We'll see how safe this town is once your eyes are looking down the barrel of a gun,'" Howard, who lives in Redlands, California, told The Huffington Post. "Those were the last words I spoke to him, and then 15 minutes later I get a phone call, he's shot in the eye."

Jordan and one of his friends were lucky enough to survive the gang shooting that took place that day; two other boys who were with them at the playground were not. Over the course of the yearlong investigation that followed, Howard -- who had previously had few interactions with police -- began to see local police officers as partners rather than patrolmen, forging bonds that would last far beyond the investigation and inspire her to begin fighting for the city's kids.

"They did not stop until they figured out who shot my boy and his friends," Howard said of the Redlands police, who eventually caught the shooters; they were convicted and sentenced to life behind bars. "I'm forever grateful to them."

Howard's attitude may come as a surprise at a time when relations between many police departments and their communities appear strained. The public remains outraged over the deaths of Michael Brown and Eric Garner and the subsequent failure to indict the police officers who killed them. In fact, there seems to be one thing nearly everyone agrees on after the months of protests those killings inspired: The relationships between American police and the communities they protect, particularly minority communities, are in need of serious repair.

"The system of policing has earned our mistrust," said Opal Tometi, a New York-based activist and co-founder of the #BlackLivesMatter campaign. In many ways, Tometi's group embodies the recent decline in relations between police and communities.

#BlackLivesMatter protests across the country have called for reforms including increased accountability surrounding police shootings and a reduction in the use of military equipment by local police departments. The shooting of two New York City police officers shortly after the announcement of the Garner verdict further intensified the national debate on policing in America.

But beyond the headlines, many police forces are working to build trust with their communities. Police experts say that improved relations can be attributed largely to common-sense approaches that build on the philosophy known as community policing.

"Ordinary, good police work is not terribly newsworthy," said Gary Cordner, a professor of criminal justice at Kutztown University, "but lots and lots of good, ordinary police work goes on every day just about everywhere."

In the wake of recent police killings, national leaders and local police departments are increasingly turning to the community policing model that cities like Redlands have relied on for years. People like Gail and Jordan Howard are proof that the model can deliver on its promise of helping police and communities work together.

At a time of strained police relations, community-oriented policing offers a different approach -- one that makes good relationships essential to good police work.

The U.S. Department of Justice's Community Oriented Policing Services office defines community policing as "a philosophy that promotes organizational strategies, which support the systematic use of partnerships and problem-solving techniques, to proactively address the immediate conditions that give rise to public safety issues such as crime, social disorder and fear of crime."

Some police departments began emphasizing community policing during the 1970s, in response to the political unrest and widespread protests of the 1960s. The nation was reeling from incidents like the 1965 Watts Riots in Los Angeles, the protests that followed the assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968, the Stonewall Riots in 1969 and a number of anti-Vietnam War demonstrations that featured violent confrontations between police and civilians. The conditions were, as they are now, ripe for reform.

In practice, community policing involves forming partnerships with community organizations, prioritizing transparency, actively pursuing feedback and establishing programs that allow police to engage with residents outside of the law enforcement arena. At its best, the practice allows community members to feel heard, respected and empowered to help police control crime in their neighborhoods, rather than feeling that officers are solely there to enforce laws through aggressive stopping, questioning, arresting and incarcerating.

"You can't arrest your way out of community problems," said Scott Nadeau, police chief of Columbia Heights, Minnesota. Nadeau took over the police department in 2008, and oversaw a shift to a community-focused approach. "That's something that I think is important for us as a community and us as a police agency to understand," he said. "Enforcement is a piece of the puzzle, but it's only one piece."

It's a strategy that seems simple, but it's far different from the way many departments operate.

Columbia Heights, an inner-ring Minneapolis suburb, was battling high crime rates when Nadeau took over, bringing with him a background in community-oriented policing. Four years later, the department won an international award for community policing after crime hit a 25-year low.

All officers in Nadeau's department are required to perform at least 10 hours of community policing activities every year, though he said most devote closer to 40 hours to the work. Officers are encouraged to choose activities that match their skills and interests. There are many choices: conducting CPR trainings, answering questions at classes for recent immigrants, serving food at a church's community dinner or holding "Coffee with a Cop" open hours, where residents are free to speak their minds with officers.

Nadeau said that community policing "wasn't always popular with [officers], it took months or years for some people to see the value." He noted that the department took care to introduce new initiatives slowly. "But I think even the officers we had that were more traditional saw the changes in the relationships between our police department and the community," he said.

Through the programs Nadeau has implemented, police hope to gain the trust of residents. But the officers themselves may also come away with a better view of community members.

"Law enforcement officers, many times, end up having ... a jaded view of police and community contacts just because of all the negative experiences that they have as a result of just doing their jobs," Nadeau said. "I think that having these positive interactions ... helps them to maybe refocus somewhat on the fact that the majority of the people in our community are great citizens and those relationships are important to both sides."

Building trust between police and the community has to start from an early age.

When Nadeau first came to Columbia Heights, youth crime rates were high, and a school board member told him that police had an especially rocky relationship with kids. Now, under Nadeau's leadership, a major focus of the city's community policing efforts is on youth. The department offers a variety of programs -- from open gym hours to one-on-one mentoring -- and officers visit each first-, second-, third- and fourth-grade classroom in the city's schools at least once a school year, building community trust from an early age. Since 2008, juvenile arrests in Columbia Heights have dropped by more than half. (Nationwide, juvenile arrest rates also fell during this period, though not as steeply.)

Officer visits to classrooms give students a chance to see "that familiar face, that this is a person that works in our community that cares about kids and families," said Michele DeWitt, principal of Highland Elementary School. This, she noted, is particularly important for students who have had negative experiences with law enforcement, like seeing family members be arrested.

Nadeau approached DeWitt a few years ago about the possibility of police doing more youth outreach. They started by getting the department involved in a bullying prevention program, in which officers would read anti-bullying books and discuss them with classes. The mentoring program followed soon after. And there's the annual visit when police let kids check out squad cars -- not surprisingly, a student favorite.

"It was a really concerted effort," DeWitt said of Nadeau's school involvement initiatives. "It wasn't just, 'Let's try this and then we'll move on and try something else,' it was the police chief really thinking outside the box and saying, 'What can we do to just inundate this community with a positive message?'"

Nadeau himself mentors a student once a week. He said that when police would walk into schools several years ago, they were greeted with alarm from teachers and fear from students, who saw their presence as a sign that something was wrong.

"Now when we walk down the hallways, the teachers smile, they're happy that you're there," the police chief said. "I probably get about 50 to 60 high-fives from some of the kids in the school. The fact that it's no longer unusual to see police officers in the schools has fundamentally changed our relationships with these kids."

Many local departments adopted community policing in response to a federal push in the 1990s.

By the 1990s, the philosophy of community policing had become widely known in law enforcement. DOJ's Community Oriented Policing Services office was formed in 1994 as part of President Bill Clinton's sweeping crime package. Created to support local agencies' community policing efforts, COPS sought to get 100,000 officers hired and distribute billions in grants. COPS Principal Deputy Director Sandra Webb told HuffPost that the office has provided community policing funding for about 70 percent of law enforcement agencies nationwide.

But while community policing can and does occur without federal support, Webb explained that attention for COPS' efforts waned after Clinton's initial investment, and the department's budget declined significantly, from a high of $1.6 billion in 1998 to just $208 million for 2015. (In 2009, $550 million was budgeted, but the stimulus package also allocated a separate one-time $1 billion for hiring officers). The George W. Bush administration actually proposed completely eliminating the COPS program in all eight of its annual budget proposals, though it was never successful in accomplishing that.

According to a Justice Department survey, the late 1990s saw a marked increase in the number of dedicated community policing officers specifically tasked with building relationships in their assigned neighborhoods: In 1997, 34 percent of all departments used such officers, while by 2000, the number had jumped to 66 percent. Similarly, there were 17,000 dedicated community policing officers in local departments in 1997, compared to 103,000 in 2000. But the survey found that starting in 2000, the number of community policing officers began to decline sharply, and had dropped by more than half by 2007.

But aggressive policing tactics gradually became more commonplace.

Mike Scott, director and founder of the Center for Problem-Oriented Policing, says that by the turn of the millennium, a confluence of factors had contributed to a turn away from a community-oriented approach toward more aggressive policing.

These included the gradual militarization of even small local departments, which began to use SWAT team-style tactics more regularly, as well as a tougher response to political protests in light of the violent showdown between police and protesters at the 1999 World Trade Organization meeting in Seattle. Police also began to rely more on strategies associated with the war on drugs, such as stop-and-frisk. In addition, "broken windows" policing, a controversial approach in which police departments aggressively pursue low-level crime, became more common in the late 1990s. Finally, after the Sept. 11 terrorist attacks, federal funds previously devoted to community policing programs were redirected to fund counterterrorism and surveillance efforts.

Starting in 2008, the Great Recession also contributed to the shift, with many police departments seeing slashed budgets -- in Redlands, for example, department staff was cut by a third. Once the federal support for community policing began to disappear, Scott argues, many cash-strapped departments that were less invested in the concept turned their attention to areas where more federal dollars were coming in, particularly counterterrorism and disaster preparedness. Cities like Redlands, which were genuinely interested in community policing, didn't change their philosophies, though they had to carry them out with fewer resources.

Though many law enforcement agencies have turned to more aggressive strategies, they haven't necessarily created safer communities or better relationships.

The result, Scott says, was a rise in aggressive policing that eroded much of the progress that community policing had made, particularly among minorities. As critics of "broken windows" have pointed out, there is little evidence that aggressive policing has made most communities significantly safer.

Scott argues that the coexistence of community policing and the aggressive approach grew increasingly "schizophrenic," essentially canceling each other out. A department's community policing arm might take a softer, problem-solving approach in a neighborhood during the day, only to have that goodwill undone by SWAT-style tactics in the same neighborhood that same night.

"If we've learned nothing else over 200 years or so of policing, it's that police will never gain either the trust of the public or improve their personal safety solely by aggressive policing," Scott said. "It's a failed strategy. It's a natural kind of reaction, but it's the wrong reaction."

With a renewed focus on community policing, plenty of cities can serve as models for others looking to adopt the philosophy.

The Justice Department has acknowledged the problem: Amid protests over Brown's and Garner's deaths, DOJ last fall announced the launch of a new three-year initiative to study racial bias in the criminal justice system and restore community trust in the police. In December, President Barack Obama again called for investment in community policing, proposing a $260 million funding package that would in part go toward providing training and resources for police reform.

Across the country, many local police departments are also renewing their efforts to change the way they interact with communities. When the U.S. Conference of Mayors convened last month, it addressed the deaths of Brown and Garner and issued recommendations that cities use community policing to improve residents' trust. From Chatham, New Jersey, to Sacramento, California, police departments are testing out new ways to improve their relationships with the communities they serve.

Redlands is one of the places where the community approach has become a fundamental part of policing. In 1993, then-Police Captain Jim Bueermann was tasked with overseeing a transition from traditional to community-oriented policing in response to strained relations between the department and the public.

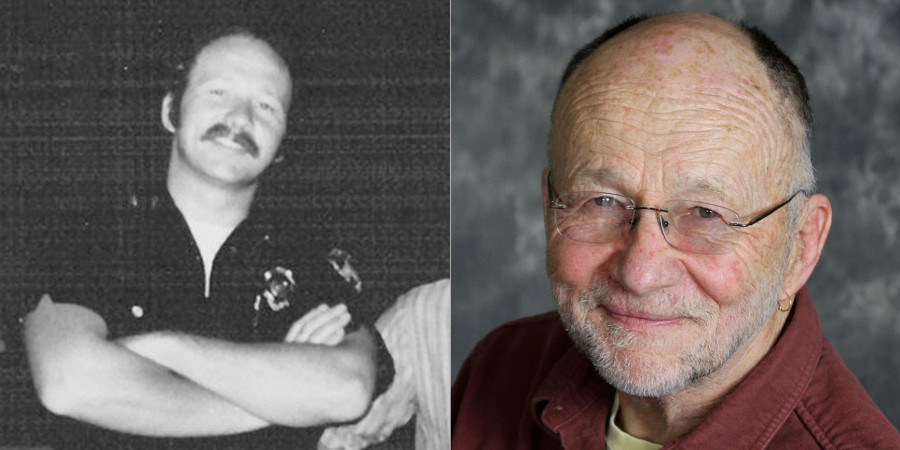

Jim Bueermann. (Photo: Alex Brandon/AP)

Bueermann, who became police chief in 1998 and served until 2011, was known for the partnerships he made and his heavy reliance on evidence-driven strategies. Under his leadership, Redlands' housing, recreation and senior services departments were consolidated into the police department as part of a program to identify risks for young people. Though the city eventually separated the departments again, the collaboration -- involving schools, hospitals, the probation department and businesses -- gave police the ability to make quality-of-life services and crime prevention a core part of their community policing approach.

"Police and community have to co-produce public safety," said Bueerman, who now heads a nonprofit dedicated to innovations in policing. "That's probably one of the strongest pieces of community policing that frequently gets missed by practitioners. They have to reach out to the community and say ... 'How are we, all of us, going to solve this problem?'"

Ed Gomez, a history professor who has lived in Redlands for 11 years, commends Bueermann for promoting peace, balance and trust in the community. Gomez chairs the city's Human Relations Commission, a volunteer advisory board that works with city officials to address residents' concerns and protect their rights. The board, Gomez said, doesn't often hear complaints about the police department. Gomez believes current Chief Mark Garcia, who took over from Bueermann in 2011, has continued his predecessor's legacy. But, he cautioned, community trust can't be taken for granted.

"That's something that will go away if it's not held sacred by the citizens and the police department itself," Gomez said. "I believe Chief Garcia is doing what he can to keep things in place the way they were, so I hope he will continue that and maybe even take a more active role. It will also be up to the community to hold his feet to the fire."

Current officers say they're dedicated to continuing a legacy of trust with residents.

"I think the community has a high expectation of us, and we have a high expectation of them back," Redlands Police Commander Chris Catren said. "When significant crime, especially, occurs, their expectation is that we're going to do everything we can to solve it, and our expectation conversely is that they're going to assist us, and they do."

And when tragedy does strike, it's easier for the community to recover when everyone is working together.

Redlands' approach was put to the test when Gail Howard's son and three others boys were shot in an unprovoked attack at a playground. Throughout the subsequent investigation, police treated the shooting as a tragedy not just for the victims and their families, but also for the department.

"Lt. Mike Reiss told me that night at the hospital, 'This is personal, they shot my son, they shot my boy'" Howard said. Reiss had been a football coach for Jordan before the shooting. Jordan, now 20, is healthy and still plays football.

The week after the shooting, the police department partnered with faith groups to lead a vigil for the victims. About a thousand people marched alongside officers from the location of the shooting to nearby Micah House, an after-school program for at-risk kids and one of the police department's partner organizations.

"The fact that they pulled together and put on a march right afterwards showed a desire to pull the community together, and it did pull the community together," said Dianna Lawson, a Micah House program coordinator. "It just made a difference."

Community policing means working proactively and building relationships in the face of tension and issues.

In the aftermath of the shooting, there was concern from residents that police weren't dedicating enough resources to the area where the incident occurred, on Redlands' north side, which Gomez described as the historically poor part of the city. Garcia said the department responded by increasing their presence in the neighborhood, stationing a community policing officer at Micah House and conducting regular meetings with local citizen groups to exchange information.

And though Howard was appreciative of the police's efforts, as the investigation dragged on, some of the relatives of the other victims accused the department of not putting enough work into the case. Howard said they and some others in the black community believed the case was not getting sufficient attention because the victims were black. She thinks this notion is false, though she acknowledged that Redlands' efforts hadn't fully erased minorities' distrust of police.

"I do feel like I'm in the middle of something, that a lot of people in the black community want me to actually hate the police, and not like the police, but I cannot feel that way," she said, referencing the national protests over police brutality. "You've got to understand where I've been and how much they've done for me."

Since her son's close call, Howard's relationship with police has helped her find ways to get more involved in the community. She took charge of the Shop with a Cop program, which allows needy kids to go holiday shopping while fostering relationships between children and police officers.

"Some of these kids, the only contact they have with police is seeing their parent be wrestled down to the ground and handcuffed, and we want them to know that there's good officers out there. ... I want kids not to be afraid to approach that police officer," Howard said.

"The crazy thing about it is at the end, you see the officers giving the kids their phone numbers, 'If you need something or someone to talk to, give me a call,'" she added. "And to me, that's a success, because now it's personal."

Each year since the shooting, Howard has held a vigil to remember the victims. She noted that the police chief or members of the force have attended every march.

But building trust isn't easy for minority groups who have long felt the police have failed them.

Even amid the best of intentions, the shift away from traditional policing can be difficult to implement. Perhaps the biggest obstacle to the community policing approach is fostering trust among minority groups.

A 2014 Pew Research poll found that while most Americans hold a generally favorable view of their local police, blacks and Latinos have much less faith in their police forces than white Americans do.

Bridging that gap by reaching out to minority groups is a key part of community policing, and the Columbia Heights police department has made it a priority. Dana Caraway, a pastoral assistant at the multicultural Church of Nations, said that her church has a robust relationship with local police. But it's difficult to surmount the historic tensions that some minority groups perceive between racial justice and the very institution of policing. The pervasiveness of those tensions came to the surface in Columbia Heights several years ago, when the Church of Nations discovered that minority members felt uncomfortable about the presence of patrol officers idling in the church parking lot.

The city of Madison, Wisconsin, began implementing community policing in the early 1980s. At that time, David Couper, who served as Madison's chief of police from 1972 until 1993, pushed his department to work in a more community-oriented, decentralized way, and also sought to diversify what was then a mostly white, entirely male department. Couper essentially invented what has been dubbed in some circles as the "Madison way" of community policing. Under his watch, the first officer focused on community policing took to the streets of Madison.

Today, the department maintains a number of community policing initiatives, including a citizen police academy, black and Latino youth academies, teams of mental health officers and community policing teams dedicated to each of the city's neighborhoods. An "Amigos en Azul" team works in the department's Hispanic-majority South District to erode the barriers between officers and the city's Latino residents.

But although the department was an early adopter of community policing and has been heralded as a success story, statistics show the Wisconsin capital still has a long way to go. The city has an overwhelmingly high disparity between arrest rates of black and white residents, with black residents estimated to be nine times more likely to be arrested than whites.

Some solutions may be perceived negatively by those for whom police mistrust is difficult to discard.

That disparity was at the heart of an open letter penned last month by an activist group called the Young, Black and Gifted Coalition, which discussed the issue of arrest rates as well as the deaths of Brown and Garner.

In the letter, the group criticized Madison's community policing efforts as ineffective, called for vast reforms to the local criminal justice system and outlined its preferred form of policing in minority neighborhoods: None whatsoever.

"Although Madison's model of community policing and attempt to build trust between the community and police, even acting as 'social workers,' may be a step above certain other communities, our arrest rates and incarceration disparities still top the nation," the letter read. "Our ultimate goal is finding alternatives to incarceration and policing, and our steps forward as a community should reflect the values of community control and self-determination."

Anthony Ward

Anthony Ward, a former Madison police officer who now works with at-risk African-American boys, acknowledged that the department has its heart in the right place when it comes to using community policing in minority neighborhoods. But in practice, he argued, the strategy results in a much higher number of officers in squad cars driving through communities of color and poor areas, which Ward believes sends a strong message to residents.

"While community policing sounds fine and dandy, what is actually happening is community seizing," Ward said. "We're not saying we won't call the police when we need help, but people in minority neighborhoods don't need to see them every time we look over our shoulder as if the community doesn't know how to take care of themselves, like we're savages and need a police presence to be civilized."

Mike Koval, Madison's current chief of police, admitted that his department has played an undeniable role in minority communities' negative impressions of the way people of color are policed. However, Koval said that instead of pulling back at this tense moment, he wants his department to "double down" on its commitment to a community-oriented approach. He thinks the time is right for officers to take on the role of problem solvers, rather than simply law enforcers.

"Right now, it's almost a calculus of a perfect storm for when community policing can really make some inroads on rebuilding some community trust," Koval said. "To me, this only creates an even greater challenge for our officers to prove our critics wrong."

Ward hopes the department will do a better job pairing officers with neighborhoods they genuinely care about and ensuring that all officers are trained in cultural awareness. Only then, he said, can an effective partnership between communities of color and police officers be formed and the disparity in arrest rates and community trust be meaningfully addressed.

"I believe minority groups are going to be the ones who are going to change our community, who are going to make it better and we can do that in conjunction with police officers, but not with them at the helm," he said.

It's a difficult task, but the conditions are ripe for change.

Like some of the skeptics in Madison, Tometi, the #BlackLivesMatter co-founder, is hesitant to embrace community policing, which she describes as "a euphemism for more surveillance" of minority communities. Tometi considers community policing on its own to be "empty rhetoric," unless it is accompanied by meaningful community investment and the altogether rejection of "broken windows" policing. She is hopeful that the demonstrations led by #BlackLivesMatter and other groups can help inspire such reform.

Opal Tometi

"Training will not help if officers do not have a fundamental shift in how they understand their roles as public servants, not as racial profiling agents," Tometi said. "For us, an end to broken windows is healing. Community investment is healing. Not more police or policing technologies for more surveillance and racial profiling."

Despite the challenges, some experts are cautiously optimistic for change.

Couper, who today is an Episcopal priest and maintains the blog "Improving Police," said he is hopeful some departments with "wise leaders and probably wise mayors in their cities" will take advantage of what he sees as an opportunity for police to take a new approach.

"We're at a position where we can take the more comfortable way and the way we do that is to maintain the status quo. The argument for the status quo is they haven't done anything wrong and to wait until it blows over," Couper said. "Or, we can show some leadership and ask: Why is it that we're so mistrusted, why are we losing support and blaming the messenger on this?"

"Change is (hopefully) coming, but from my experience it will take a long, long time," Couper said later, when asked specifically about the racial tensions in Madison. "But why not start now?"

And sometimes even small gestures end up going a long way.

"You can't always solve them, but people need to see police trying to solve the problems that the people who live there regard as problems, to see them working on their behalf as opposed to pursuing their own interests or something else," said Cordner, the Kutztown professor. "You can't just repaint the police cars or hire a new police chief."

"Policing is frequently not pleasant, sometimes it's very complicated and just messy," Bueermann said. "A police department's ability to weather a controversial incident -- it's almost always involving use of force -- is a direct function of the trust and confidence the public has in that department."

Nadeau acknowledged that the national focus on police brutality and mistreatment of minorities has had an effect on residents' impressions of police in Columbia Heights. But he believes that a fundamental part of his job is to engage those concerns, and to actually implement the feedback he gets. So, when Caraway told police that residents were responding negatively to officers idling in the church parking lot, the department ended the practice and met with the congregation to address the concerns. It was a small act, but an example of the philosophy that, over time, may be one of the best chances to repair the damaged relationships between police and the public.

Are police in your community making unique efforts to inspire change and improve relationships? We want to hear about it. Send your stories to goodcops@huffingtonpost.com.