Shin Dong-hyuk drew worldwide attention to the harsh realities of the North Korean regime with the 2012 book, Escape from Camp 14. The book details the young North Korean's life in one of the country's notorious labor camps as well as his subsequent escape to the South.

Since the publication of Escape from Camp 14, Shin has been an outspoken critic of North Korea's human rights record. He even testified before a United Nations Commission of Inquiry about his ordeal in order to bolster a UN resolution on North Korea’s crimes against humanity. A member of the commission called Shin the “single strongest voice” on North Korean human rights.

However, in January 2015, Shin responded to attacks on his credibility by North Korean officials and other defectors, and admitted there were inaccuracies in his original account. Shin revealed that he had changed crucial details of his story, including the circumstances leading up to the execution of his mother and brother and the age at which he was tortured. He also admitted that while he had initially testified that he had spent his entire North Korean life in Camp 14, a particularly notorious labor camp, he had in fact spent years living in Camp 18, which had a less draconian reputation.

A majority of observers agree that while details of Shin’s story may have been changed, the essential facts of his account -- which involve incarceration, torture, the execution of family members, and escape -- are true. Shin has kept his silence during the controversy, communicating solely through his biographer, Blaine Harden. Last month, however, he agreed to an interview with the editors of The Huffington Post Korea. Below are excerpts from the interview, which was initially published in Korean and has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Photo by Sung-ryong Kim/ Studio Bob

Photo by Sung-ryong Kim/ Studio Bob

There’s been serious controversy over the changes in your statements, particularly in the parts about Camp 14. You admitted that you changed the age at which you were tortured.

I acknowledge the recent controversies have been problematic. If people only inquire "Why did you report the age you were tortured as 13 years old instead of 20," I don't have any answers. It is better to say that there are things I chose not to share, rather than to say I altered the story. There were things I could not reveal as a human with dignity. If I knew my life would become what it is today, I would have shared everything, no matter how painful and hurtful it would have been for me.

Everything I have shared until now is a first-hand account of things I saw and experienced. The marks of torture endured in Camp 14 remain on my body and they show how I was hung upside down, naked. The imprints of hooks that struck me are still with me. The traces of the nails that were uprooted from my hands, a finger joint that was lost and the marks of shackles on my ankle prove my experience. The burn marks still remain on my butt, along with the burn when I was set on fire. When I screamed because of excruciating heat and when blood gushed out, my desperate cries back then, those situations are all perfectly describable. While I was able to withstand those things, there were other things I wanted to conceal.

What did you want to hide?

The fact that my mother and brother were executed because of my report.

Why didn’t you tell the truth from the beginning?

I was ashamed. Who can tell such a story without shame? In North Korea, people are so heavily ideologically educated that even when it is your family member who is doing wrong, you are supposed to report them. I was only 14. My mother and brother spoke of escape and I reported them. The next day a camp officer called and placed a paper on a desk. They then told me that they would do anything I wanted if I left a thumb mark on the paper. The document detailed that my mother and brother murdered someone. Without realizing the severity of the situation, I pressed my finger on the document. Then the next day, everyone started asking how my mother and brother murdered someone. I found out a week later that an officer went to rob a village and ended up beating a woman to death, and he blamed it on my family. I heard that through other people, but there was nothing I could do as a convict.

On the day of the public execution, my father and I were dragged to the site and seated in the front row. My mother’s body was badly bloated and I wasn’t sure if it was because she had been starved or was beaten to that point. Later I heard that she had pleaded with the officer to give my brother her portion of food and starved. My mother looked at me at the last moment, while they were dragging her, but I was unable to look her in the eye. My mother was hung and my brother was shot.

Some ask how I could report my own mother, but that’s how the environment is set up there. In the camp, you feel like that’s the right thing to do. In the camp, my father and mother were both just prisoners. I would call her mother in name, but I never got to spend any time with her. I grew up not knowing what family was. No one welcomed me into the world when I was born in the camp. In there, everyone is just equal as prisoners. No such thing as emotion exists.

How can they publicly execute people in front of their own family members, even in North Korea?

That is North Korea. They tried to gather as many people as possible for public executions. More witnesses will yield greater effect. Recently, people have been talking about the cruelty and gruesomeness of the Islamic State group’s public execution videos, but that is because they are available to be seen. The things that are happening in North Korea are unseen but much more atrocious.

Why did you decide to overturn your testimony?

North Korea released a fabricated video that deviated from the truth. I was indignant that they used my father, who is still suffering in North Korea, to lie on their behalf. They charged my mother and brother with murder to explain their execution and portrayed me as a comfortable student. They even called me a sex offender. All I did until last September was discus the camps as they were, but once the video was released, the nastiness of North Korea infuriated me. Then I realized I should not hold anything back. The most important reason why I could not reveal all of the truth was because of my family.

Do you regret your work as a North Korean human rights activist?

I did not want this lifestyle. It is not all fun and games to fly to the United Nations to tell people about my suffering. What I still think to this day is, “Why did I step into human rights work, I could have lived under a rock.” Some people may never imagine how difficult it is to testify about excruciatingly painful memories over and over. Every time I talk about something, it visits me in my dreams that night. It feels as if I am replaying the past nightmares that I would rather forget about.

Not many people pay attention to North Korean human rights issues.

It is a sad truth. People in South Korea have become immune to this and do not pay attention anymore. After the controversy, when I read the comments sections on some articles, there were people telling me to just die. They criticize me for going to the United Nations. However, it is horrifying that there are groups in South Korea who praise the North Korean dictator. We must try to end the pain that we went through ourselves, but that is only possible with the help of the global community. This indifference, this atmosphere where victims of the dictatorship are being criticized, isn’t it unfair? It is horrible and awful.

Will you continue your North Korean human rights activism?

What I do well is bothering North Korea. It is my duty to turn the North Korean regime upside down. I have never said such things in the past. But now, my goal is to overturn North Korea, bring dignity back to my family and get rid of all labor camps.

North Korea must accept investigators and I must meet my father to find out why he was initially taken as a political prisoner. I will go back to the labor camps with the UN Commission of Inquiry in order to do so. I don't think that's impossible.

(Editor’s Note: HuffPost Korea’s editors asked to photograph Shin’s scars during the interview, but he declined the request. However, after the interview, he released the following pictures on his official Facebook account. Shin wrote that he released the images to let people know how a dictator feels pleasure while giving the worst of suffering to the people. "I will be posting every single torture scar that I have," Shin said.)

Shin claims these photos show the marks left by torture on his body. He says he sustained these scars when he was shackled upside down, while being burned.

Shin claims these photos show the marks left by torture on his body. He says he sustained these scars when he was shackled upside down, while being burned.

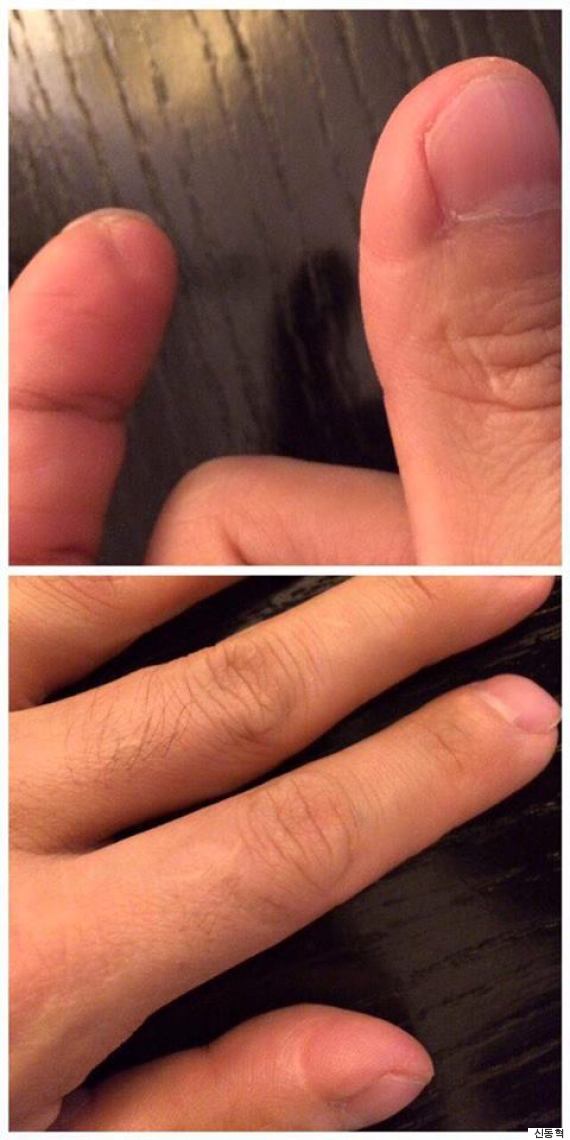

Shin says these pictures show the traces on fingers that were created by a machine that pulled out fingernails. He also claims that the pictures show a lost fingertip and evidence of his fingernails growing abnormally because of the torture.

Shin says these pictures show the traces on fingers that were created by a machine that pulled out fingernails. He also claims that the pictures show a lost fingertip and evidence of his fingernails growing abnormally because of the torture.

Talia Lavin contributed to this story from New York.

Related

Before You Go