This story originally appeared on Citylab.

A substantial share of America’s youth remains economically disconnected, even as the economy continues to recover. More than one in eight—13.8 percent—of young Americans ages 16 to 24 are neither working nor in school, according to a new report from the Social Science Research Council’s Measure of America project. The study is based on data from U.S. Census Bureau’s 2013 American Community Survey.

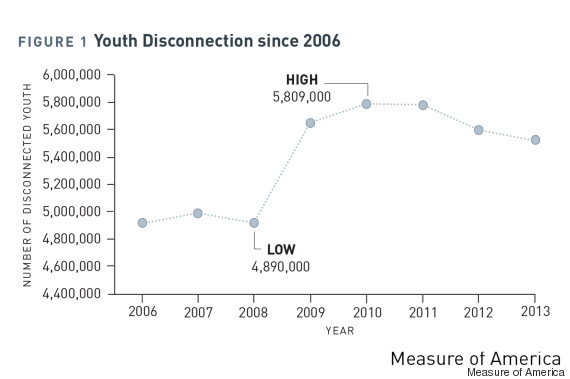

The chart below, from the study, shows rates of youth disconnection since 2006. In 2008, on the eve of the Great Recession, a low of 4.9 million U.S. youth were “disconnected,” or not at work or in school. But by 2010, just two years later, nearly an additional million youth had joined their ranks. And though the economy had improved considerably by 2013, the number of disconnected youths decreased only slightly, to 5.5 million.

Why does youth disconnection matter? The study’s authors find that one’s employment or educational status in the critical early years of life matters a great deal to future career prospects. Young people build confidence in their first jobs or secondary-schooling opportunities, “which in turn [breeds] future success,” according to the report. They also develop social and emotional skills, which are critical to obtaining and then maintaining jobs. As the report’s authors point out, “First jobs help teens and young adults develop soft skills like punctuality and collaboration, learn the unspoken rules and behavioral norms of the workplace, and forge networks of mentors and connections.”

Young people who are not working or in school between the ages of 16 and 24 are nearly twice as likely to live in poverty, three times as likely to have left high school prior to obtaining a diploma, and half as likely to hold a bachelor’s degree than their connected counterparts. For young women, the stakes are even higher: Young women disconnected in these critical years are three times more likely to have a child. As the report notes:

Connected girls have strong incentives to delay the joys of motherhood until they have finished school, saved money, lived independently, gained a foothold in the working world, and have a committed partner; girls whose options are very limited have far fewer incentives to put off a meaningful and fulfilling marker of adulthood that is within their grasp.

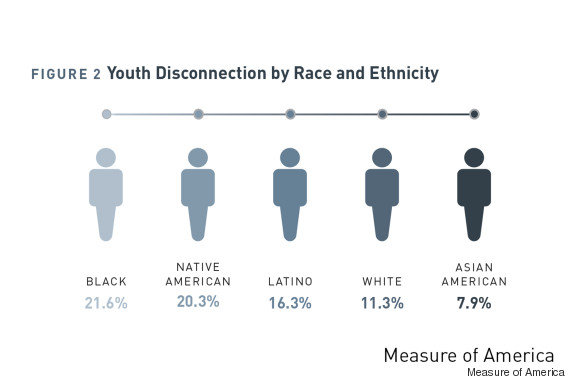

The burden falls particularly heavily on youth of color. More than one in five (21.6 percent) of black youths are disconnected, and one in five Native American youths (20.3 percent) are, as well. Meanwhile, just 11.3* percent of nation’s white youths are disconnected. The chart above, from the study, shows the racial breakdown.

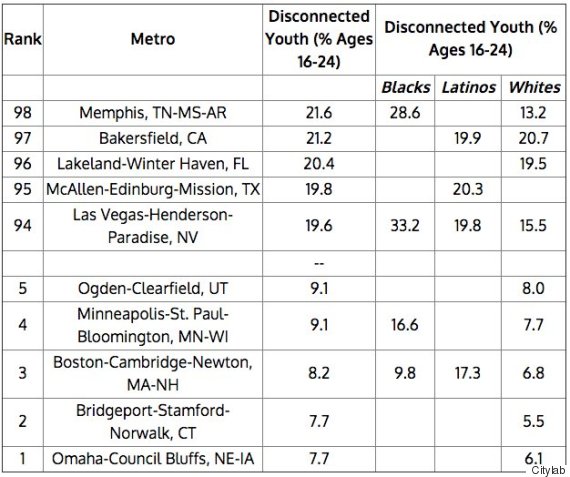

What do youth disconnection rates look like in specific metros? The table below, based on the study’s data, shows the pattern for the top and bottom five cities out of 98 of the country’s 100 most populous metro areas. (Blank spaces indicate that the metro area is too small for reliable estimates.)

Generally speaking, the metros with the highest levels of youth disconnection are concentrated in the South and Sunbelt: Bakersfield, California (in which 21.2 percent of youth are disconnected); Lakeland-Winter Haven and North Port-Sarasota-Bradenton, Florida (20.4 and 19.0 percent); McAllen-Edinburg-Mission, Texas (19.8 percent); Las Vegas (19.6 percent), August-Richmond County, in Georgia and South Carolina (18.7 percent); and Baton Rouge and New Orleans, Louisiana (18.6 and 18.2 percent).

Meanwhile, the metros with the lowest rates of youth disconnection tend to be in the north and Midwest: Omaha-Council Bluffs, Nebraska and Iowa (with 7.7 percent of its young people between 16 and 24 qualifying as disconnected); Bridgeport-Stamford-Norwalk, Connecticut (7.7 percent); Boston-Cambridge-Newton, Massachusetts and New Hampshire (8.2 percent; and Minneapolis-St. Paul-Bloomington, Minnesota and Wisconsin (9.1 percent).

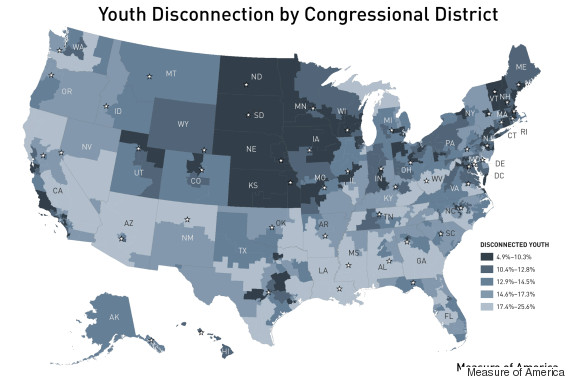

The map below, also from the study, charts youth disconnection by congressional district. The lightest colored districts are those with the highest rates of disconnection, between 17.4 and 25.6 percent. The darkest districts, by contrast, have the most youths between 16 and 24 either working or in school, between 4.9 and 10.3 percent. (Note that the unemployment rate in 2013 was 7.4 percent for all American citizens. That means even the districts with the lowest rates of youth disconnection often have more youth out of work or school than adults. Clearly, the economy has been tough on young people.)

Here, we see the metro pattern repeated on a larger scale. High rates of disconnected youth tend to be in counties in the Deep South and the Sunbelt, especially Louisiana, Arkansas, Georgia, New Mexico, Arizona, Nevada and California. (The counties with the very highest rates of youth disconnection—like Wheeler County, Georgia, in which 82.0 percent of youth are out of work or school—tend to host sizable prison populations.) By contrast, there are fewer shares of disconnected youth in counties in the Plains, northern, and northeastern states—Nebraska, Kansas, North Dakota, Montana, New York, and Vermont—as well as pockets of California and Texas.

The economic toll of our disconnected youth today is staggering: The total costs stemming from incarceration, subsidized health care, and public assistance for disconnected youth amount to more than $25 billion annually, according to the report.

This troubling, tragic, and costly pattern magnifies the increasingly spiky and unequal nature of the American economy.