My grandfather once said himself, "The Post is my best and only opportunity to express myself fully." He liked to come up with his own stories and tell them his way -- and the Post covers were the best way for him to do that. With other illustration work he was forced to rely on and stay true to someone else's story. Without the unique opportunity that The Saturday Evening Post afforded him for so many years, it could be argued that Norman Rockwell would not have evolved into the incomparable and beloved storyteller we know today.

Pop, as we called him, always wanted to become a great illustrator -- he was driven from the moment he started sketching while his father read Charles Dickens to the family. As he wrote in My Adventures As An Illustrator, "You start by following other artists -- a spaniel. Then, if you've got it, you become yourself -- a lion."

His dream was to do a cover for The Saturday Evening Post, but he was haunted by doubts. Only the very best, like J.C. Leyendecker and Coles Phillips, did covers for the Post.

He began a routine of sitting alone in the studio he rented with his friend, the noted cartoonist Clyde Forsythe, a copy of the Post spread out before him, and allowing himself to dream... to dare to visualize a picture he had painted on its cover. How many people would see it -- one million, even two million? His name in the lower right hand corner? What would it be like if he were the man he wanted to be ... a famous illustrator, adored by female fans, his covers displayed on newsstands, tucked in the mailboxes of families around the country, perhaps children would playfully fight over who would get to see the cover first and explore all its details. He even pictured himself dining with the Post's larger-than-life editor, George Horace Lorimer.

One day Clyde found him on the sofa, suffering over the fact that none of this was even close to becoming a reality. Clyde had to convince Pop that he was indeed good enough to at least attempt a cover, to not let himself be intimidated -- "Lorimer's not the Dalai Lama."

So my grandfather got to work. Two ideas came to him, conjured up from the kind of covers he had admired on the Post. The first was a Gibson Girl kind of painting with a dashing man bending over a sofa to kiss an irresistible, but removed, high society woman; the second, a young ballerina bowing before an audience in a dramatic spotlight. Clyde took one look at the paintings and exclaimed dryly, "C-R-U-D." The ballerina looked like a "tomboy who's been scrubbed with a rough washcloth and pinned into a new dress by her mother. Forget about what you think the Post is looking for and paint what you do best -- kids."

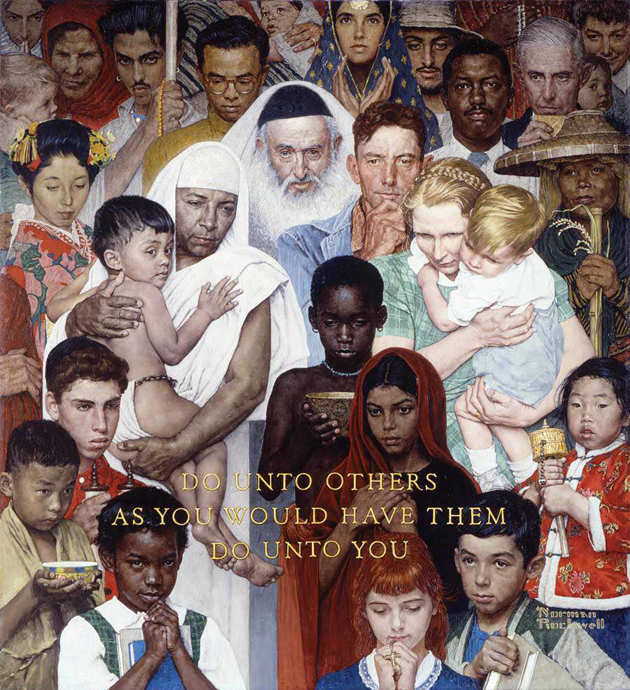

"The Golden Rule," April 1, 1961. Courtesy of Curtis Licensing, SEPS.

To assume his new identity as a successful illustrator my grandfather bought a brand new suit -- in a fashionable gray Herringbone tweed -- along with a conservative new black hat. He had a custom-made "suitcase" created to take the paintings on the train to the Post in Philadelphia. The case looked more like a small black casket. Despairing thoughts followed him all the way. But miracle of miracles, Lorimer accepted two paintings and three sketches for future covers. His first cover, Salutation, appeared on the cover of The Saturday Evening Post on May 20, 1916 -- Pop was only 22 years old.

My grandfather used one of his favorite models, Billy Payne, for all three boys in this first cover. The boy pushing the pram is fully realized and rendered, but the other two boys are poorly done. He should have used three distinct boys to model for the painting. And the dark hollow of the pram and barely visible baby were probably the result of nerves. Pop must have been anxious about painting his first Post cover and perhaps couldn't quite deal with getting an actual baby as a model with its very real wriggling and crying to contend with!

He often recalled the fun and hard work of pitching his ideas to Lorimer. He would place the sketches in front of Lorimer on his desk and then act them out to bring the whole picture and story to life in an exciting way. He wrote in the first edition of My Adventures As An Illustrator:

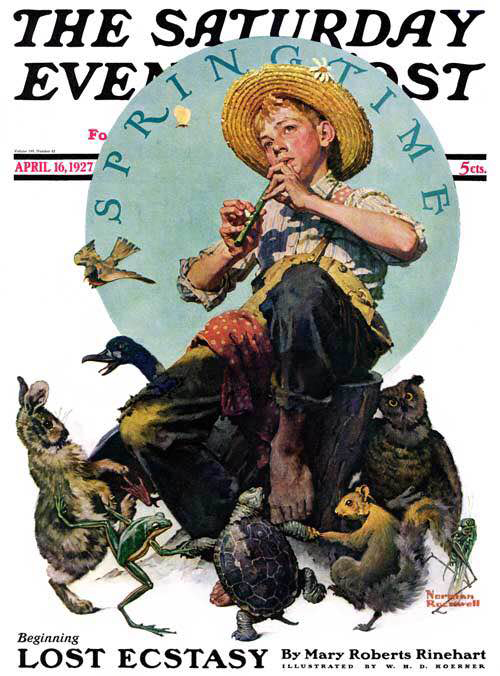

"I'd get up from the chair, shake myself and point to one of the sketches on the desk. 'Springtime,' I'd say, 'a little boy perched on a stump playing a flute.' And I'd sit on the edge of a chair, pull up my legs from the floor in a graceful pose, and make believe I was blissfully blowing a flute. 'The kid's happy,' I'd say. 'It's spring. The sun is warm upon his neck; the bees are buzzing in the flowers. And the little animals are dancing in a ring about the stump. A rabbit, a duck, a frog' -- I'd kick up my heels and dance around the chair -- 'a turtle, a squirrel, an owl, a grasshopper. It's spring. Everybody's joyful.' 'Good,' Mr. Lorimer would say, scribbling 'OKGHL' on the side of the sketch."

That sketch ended up as Springtime, the April 16, 1927 cover.

Rockwell's time at The Saturday Evening Post can be divided into three periods: the three editors, along with one significant art editor, that oversaw the magazine until my grandfather quietly resigned in 1964. He always remembered being greeted by Lorimer standing behind his desk, silhouetted by the light from two expansive windows in back of him. When Lorimer died it was like the end of an era, the closing of a large volume not only of Norman's life, but also the end of Lorimer's reign. "The Great Mr. George Horace Lorimer, the baron of publishing", as my grandfather would affectionately refer to him, had the strength and unwavering decisiveness that Pop so admired. Lorimer's Kentucky-born determined square jaw and commanding eyes rested on my grandfather with a mix of palpable power softened with kindness. He made sure he approved of Norman's choice of partner when my grandfather married his second wife, my grandmother, Mary. Lorimer was an important father figure and mentor to my grandfather and Pop remained somewhat in awe of GHL's formidable, intimidating, yet reassuring presence for the rest of his life.

Always unreasonably in fear of the Post dropping him at any moment, despite his growing fame and success, Rockwell felt even more precarious when Wesley Stout came on board as editor succeeding Lorimer. Stout wasn't as definite as Lorimer, he seemed to look for what was wrong in each of my grandfather's paintings instead of what was right. This whittled Pop's confidence down until he didn't feel good about any of the work he was turning in.

"Voyeur," August, 12, 1944. Courtesy of Curtis Licensing, SEPS.

But five years later Ben Hibbs replaced Stout as editor. He was a Midwesterner, much more casual, and he genuinely liked my grandfather's work. He resurrected The Saturday Evening Post at a time when the magazine desperately needed it. He had the cover redesigned so that full paintings were shown, not just vignettes of one or two people with almost no background. The logo was streamlined into a more modern Post font in the top left corner. This freed Rockwell to take his stories to a whole new level of detail, atmosphere and character. Most of the limitations that had hampered him were no longer there. The canvas before him was now wide open with more possibility (and much more work!). Ben Hibbs was the one, after all, who enthusiastically accepted and championed the Four Freedoms, placing them inside the Post after the government had rejected them. (The government would later relent, touring the paintings around the country to raise money for war bonds.)

While Hibbs was editor, Ken Stuart became the new art editor in 1945. He is credited with changing the direction of the content of the covers, moving them towards the celebration of America and loftier, more expansive ideas. But Stuart was a small man with a tremendous ego; he wanted to dictate content to his artists and control them. He had been an illustrator himself before becoming an art editor and perhaps felt entitled to have that much input. But my grandfather felt that Stuart over-directed at times. Their relationship was conflicted and ambivalent at best. Stuart went so far as to paint a horse out of one of the covers, Before The Date, September 24, 1949, without telling my grandfather. Pop threatened to leave the Post -- my grandmother, Mary, was absolutely furious; she had never liked Stuart. But after it was arranged that Bob Fuoss, the managing editor, and Ben Hibbs would oversee all matters regarding my grandfather, Stuart was tolerated and Pop even did what he could to butter him up, inviting him to my parents' NYC wedding in the 50s.

The conflict between the two men still lingers today. Stuart claimed that Pop "gifted" several paintings to him, Saying Grace, The Gossips and Walking To Church. No communications were found from my grandfather to Stuart other than Pop asking for his paintings to be returned in the 50's and Stuart refusing this request, citing a company issue. My grandfather felt that Stuart simply took the paintings out of the Curtis building one day and held on to them. The Stuart sons recently sold Saying Grace, my grandfather's most popular cover, and the two other paintings at Sotheby's for $57.3 million dollars, a figure that would have astonished and probably embarrassed my grandfather.

Most people today do not realize that during Rockwell's tenure, The Saturday Evening Post prohibited its artists from painting people of ethnicity in any role other than a subservient one. This never sat well with my grandfather. He would sneak African-Americans and people of ethnicity into his paintings where he could -- Statue of Liberty, July 6, 1946, for example. He cleverly turned this policy on its head in his December 7, 1946 cover, New York Central Diner. In it, a young boy in the train's dining car is trying to figure out the check. But it is the African-American man, the waiter, who is the heart of this painting -- the viewer's eye goes to him because his presence is so immediately felt, he radiates such kindness and bemusement at the boy's dilemma.

In my grandfather's paintings everything is said without words. The entwined legs of the two lovers in Voyeur, August 12, 1944, reveal a quiet, unspoken and immediate intimacy, and are the most prominent visual -- though the little girl in red sneaking a look at the lovers is sharing in their secret. It is one of my grandfather's more intimate works, yet it takes place in a very public space, the brightly lit passenger car of a train. This contrast makes the cover touching and effective. The exposing overhead light doesn't matter to the two lovers who are in their own private world, not even noticing the little girl leaning over the seat in front of them. We feel we are an amused, unseen observer on that train. Note the contrast between the young woman's polished, stylish shoes and the soldier's lived-in service boots.

"Salutation," May 20, 1916. Courtesy of Curtis Licensing, SEPS.

Like Van Gogh, Norman Rockwell was a master of shoes. Shoes can sometimes reveal more about the real life of a character than the face -- the wear and tear, even with a good polish, still remains, the sole reveals the soul. Faces can hide aspects of personality through facades, cosmetic artifice, glasses, expressions, etc.There are many instances of Rockwell's quiet focus on shoes, and also his frequent contrasting of new and old shoes: Breaking Home Ties, The Tattooist, Rosie The Riveter, The Game, Auld Lang Syne, Furlough, Hatcheck Girl, Double Take, Starstruck, Dreams of Long Ago, The Scholar, The Full Treatment, Crackers in Bed from the Edison Mazda series, and the list goes on and on. The Bookworm actually shows a man wearing two entirely different shoes -- a perfect, subtle way to show that this man is in his own world and too distracted to worry about matching shoes!

My grandfather loved to paint older people and children because of the clear contrast they represented: the old visited alongside the new, the unrelenting process of aging and the loss of innocence that we all have to move through. An older face tends to show the trials and tragedies the person has had to endure. There is either a softening or hardening of the features that occurs over time which forever etches itself onto the face -- less artifice, even less of an attempt or ability to hide the truth, the failures, the secrets and lost dreams. Children have an essential purity of reaction and an often unsuppressed sense of play, adventure and possibility -- they remind us of our own youth, when life was perceived as simpler, freer.

Successful, beautiful people, primped and perfect, held no interest for Rockwell, he saw their faces as masks rather than fascinating maps of character. Coles Phillips, a fellow illustrator in New Rochelle, used to rib Pop about the content of his pictures. Why wouldn't Rockwell just paint pretty girls like he did? Rockwell would respond doubtfully. Could he even paint an attractive, alluring girl like Phillips or Charles Dana Gibson? My grandfather actually created this fiction that follows him to this day. Perhaps it stemmed from his insecure days as an awkward youth with pigeon toes and a long neck who didn't feel attractive to women yet. As he matured as an artist he realized that he would never paint pinup girls like Vargas, Petty and Elvgren -- he was always too interested in character. Even in the many beautiful women that he painted throughout the years he added touches of character like slight pigeon toes, self-doubt in private moments or real grit, moxie, strength and determination.

The constant struggle for ideas was the most difficult part of doing the Post covers -- he would often drive himself to a place of absolute exhaustion, despair and doubt during the evening after leaving the studio, working for hours at the dining room table penciling idea after idea in a flurry of sketches. The next morning he would awake, unable to eat, rubbed raw, vulnerable, uncertain... But that was when an idea would sometimes strike him. Receptivity comes when one's defenses are worn or broken down -- he would deliberately put himself through this seemingly destructive process to find the golden ideas. Later my grandfather began to discover some of his better ideas while shaving. As any artist knows, it is usually when you let up on the pressure of thinking of an answer to your artistic dilemma that the inspiration comes in an unexpected flash, when you're doing something trivial and mundane and the mind is calm. Some of his ideas would come from trends or news of the day -- the invention of the radio, the first car, or fads that drew the public's attention; progress that touched everyone's lives and changed them. As Norman Rockwell grew up and matured as an artist and man he brought his audience -- his friends -- along with him. In that way he painted his story, their story and the country's story -- all thanks to the high visibility of his work on the cover of the Post.

New York Central Diner," December 7, 1946. Courtesy of Curtis Licensing, SEPS.

Pop always wanted to "get the feel of a place" that he was going to paint, he searched for the smallest details that would make his picture "ring true", including the actual attire, props and accessories of the period. That is what makes it fun to explore his paintings -- every detail is carefully chosen, a clue, a secret that is connected to the story. He was a "method" actor and director before anyone knew what "method acting" was. Many of his paintings and covers became a sort of sense memory exercise -- trying to capture and recall the atmosphere he had immersed himself in, like the prize fight in NYC or the blacksmith's shop in a small town in Vermont where he spent the whole morning -- what it felt like to be in that room or environment, the smells, sounds and visuals. He immersed himself in the reality he would be painting in order to bring that reality to the viewer.

All great art is a search for what is true, it is an effort to convey that discovered truth. Pop spent hours in Louisa May Alcott's home for his series on Little Women, exploring the attic where she used to do her writing and contemplation. He visited and absorbed Mark Twain's childhood town of Hannibal to research his illustrations for Tom Sawyer, he even went to the extreme of being left alone in the cave from Twain's novel that Tom and Becky get lost in. He sketched by himself in the light of a flickering lamp surrounded by the enveloping darkness, envisaging the cave as the lair of escaped robbers. Rockwell's vivid imagination was the engine that drove him all those years; an imagination that never tired of thinking up possibilities, new horizons, and fresh adventures. But it was often a constant struggle because of periods of self-doubt, and the fear that there was a lack of expansion and growth in his work.

It is a revelation when you look at the 322 covers he did between 1916 and 1964. The progression of his work, his vision, his technique, and storytelling skill deepened and expanded in surprising ways. You can see his evolution as an artist and marvel at his refusal to stay in one place with his work.

People found reassurance, humor, empathy, compassion and kindness in his covers. Through almost half a century of The Saturday Evening Post covers he left the public with the resonating and quiet reminder of the goodness in people: we are struggling, celebrating, learning and growing each day -- we are all in this together. And people continue to find this solace, this inspiration in his work; the remembrance that all is, indeed, well. It is an invisible ideal that most Americans and people around the world instinctively hold in their hearts, an ideal that becomes manifest through the actions of people towards themselves and one another. That is what lives in the best of my grandfather's work and in the best of all of us.

"It is no exaggeration to say simply that Norman Rockwell is the most popular, the most loved, of all contemporary artists. . . While the face of the world was changing unbelievably, Norman has amused, charmed and inspired a great many millions of Americans. The fact that he has managed to capture the hearts of so many people is easy to understand when you know him, for somehow he himself is like a gallery of Rockwell paintings -- friendly, human, deeply American, varied in mood, but full, always, of the zest of living." ~ Ben Hibbs

"Springtime," April, 16, 1927. Courtesy of Curtis Licensing, SEPS.