The severity of the Ebola outbreak hit home for me on Aug 4, 2014. This was the first of a series of mandatory quarantine lockdowns for the city of Freetown (and the nation overall), Sierra Leone's capital city and my home since February. The government's orders to stay put silenced an otherwise teeming, congested city of more than 1.2 million people. I saw the city fall to a hush, and the police cars patrol the empty streets.

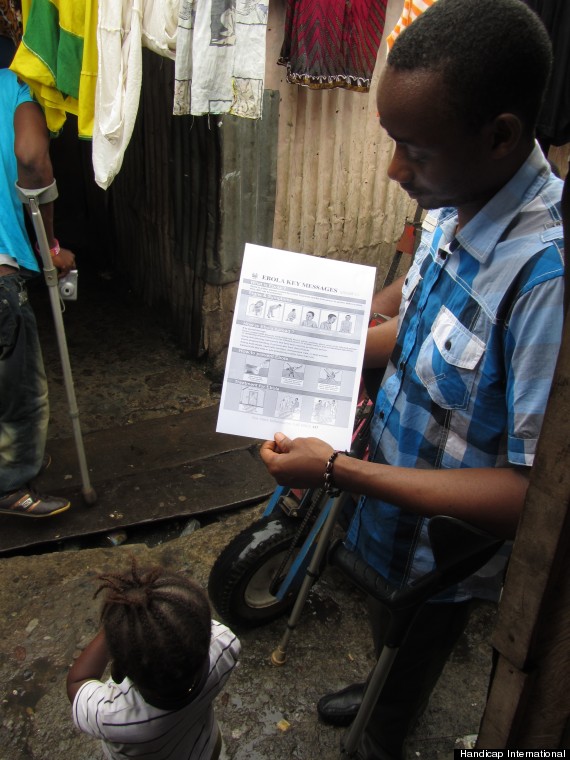

Ebola sensitization session in an overcrowded, shanty town of 90 disabled people and their families. Photo: Handicap International

Freetown's pause was meant to stem the tide of infections in Sierra Leone, but my colleagues and I were worried. This type of generic, universal quarantine had the potential to instill even greater fear than what was already present, potentially driving the outbreak's expansion. Also, we knew that one particular group -- people with disabilities, estimated at about 15% of the global population -- would find themselves in a dire situation during these quarantines. Here people with disabilities often support themselves informally through odd jobs or begging, living a day-to-day existence with no stockpiles of food, water or other essentials.

Long before Ebola began its deadly rampage through Sierra Leone and nearby Liberia and Guinea, our teams had focused on developing the country's rehabilitation capacity, maternal and child health projects, and encouraging communities to open their doors wide for children with disabilities to learn, for adults to earn a wage, to vote, and more. Handicap International has worked in Sierra Leone since 1996, when we began to support victims of the country's civil war.

People with disabilities are at the heart of our actions not just here, but in all of Handicap International's 60-some countries of operation. The world's largest "minority group," they are often marginalized and extremely vulnerable due to the barriers placed around them by institutions, their physical environment, and community attitudes and beliefs. These barriers appear in every society, but they feel especially prohibitive in low-income settings like Sierra Leone, and are compounded during humanitarian crises.

Unfortunately, we do not know what is the percentage of Ebola cases amongst people with disabilities -- the official data is not disaggregated in a comprehensive way. However, thanks to Handicap International's intimate partnerships with national and community-level disabled people's organizations, regular, two-way communication keeps us privy to how the crisis specifically impacts this population. Blanket Ebola awareness messages have been ineffective at reaching people with disabilities due to their geographic and social isolation; message mediums have also failed to inform those with hearing, visual and cognitive impairments.

The best way to slow the Ebola outbreak is shine light on it -- giving the public clear, uniform and timely information about the disease and how it can be contained. Yet a sign with illustrations showing proper hand washing, Ebola symptoms, and steps to take if an infection is detected is useless to someone with limited or no sight. A message broadcast by radio, or by bullhorn in the street means nothing at all to someone who cannot afford a radio, or hear in the first place. Even for those who avoid infection, they must endure the secondary impact of the crisis on an already fragile economy and public services.

So when the government opened Freetown's streets again after that first, eye-opening day of silence, and asked NGOs like ours to focus on prevention, we mobilized. Working with partners like the National Commission for People with Disabilities, African Youth with Disability Network, One Family People, and a fleet of disabled persons organizations in and around Freetown, we organized awareness sessions at schools, institutional living centers, and communities for people with disabilities.

The meetings aimed to dispel the idea of Ebola as a faceless killer. The beneficiaries challenged us -- was Ebola real? Was it malaria repackaged? Was the illness a fabrication of the government? Were witches or demons to blame? We talked about germ theory and gave them the opportunity to bring up their beliefs and theories in order to address them together.

The beneficiaries relayed a continuous message to our team: these meetings were their "first and only" opportunity to learn the truth about Ebola. Experience tells us that many more vulnerable people would have missed these simple safety messages, too. A rapidly spreading communicable disease cannot be contained if prevention and response is exclusive.

Since July, our existing projects have begun shifting their focus to Ebola disease prevention. Other projects have been suspended completely in order to support the government's response. Only our inclusive education project, severely hampered by the closure of schools, has kept elements in play by using the downtime at schools to install accessible ramps and other adaptations. In the meantime, we've kept a close eye on the 1,500 children with disabilities attending inclusive schools. With their schools shuttered, our staff work to ensure they know how to take the right measures to remain healthy.

One of the students supported by Handicap International is 14-year-old Emmanuel James, who lives with his father, a blacksmith who is also living with a disability. Emmanuel's father cannot earn a living since his business depends on cross-border traffic, and that border is closed. Emmanuel's school is broadcasting lessons on the radio, but these are lost on Emmanuel, because his father doesn't have the money to buy a radio. We call Emmanuel and his father regularly to ensure they are safe.

Around the country, the number of cases has increased, and the death toll is mounting. Recently, the military began monitoring a housing compound next to our offices, after a nurse living there was infected, placing everyone living with her under quarantine. Simultaneously, we began to conduct formalized field assessments, which we have parlayed into the blueprints for targeted community mobilization efforts.

To do this, we established an inclusive technical unit to ensure vulnerable populations are included in planning and response initiatives. This unit is not only designed to support Handicap International's efforts, but also to assist the government's coordination and response mechanisms, as well as, those of NGO partners. Local staff members are interviewing people with disabilities and their families, comprehensively assessing how this community is faring amid the crisis. Crucially, the technical unit works to ensure that all vulnerable populations have access to information and services and that they are included in the planning and response process.

What's more, the unit provides technical trainings for response partners, allowing them to ensure that their activities -- at all levels -- are inclusive of vulnerable groups, and that participation by these vulnerable groups is mainstreamed into planning and implementation. Handicap International is also providing some limited supervision and support at the chiefdom and village level to ensure that community mobilization activities involve representatives of vulnerable individuals, and that their input and needs are being addressed.

We're also chairing the National sub-committee for Special Needs, which sits under the National Pillar for Social Mobilization, and informs its actions.

The impact of the epidemic goes far beyond the risk of contamination. Buying food or even non-food items like soap is a luxury for some families. When the government enforced a three-day quarantine in late September, we organized a food drop for beneficiaries -- to avoid the fear we'd all had on Aug. 4, that people with disabilities would suffer more than most. Our work is far from over. We will continue to look for the best ways to work with and support this important community, as well as those under quarantine or recently discharged to ensure they have what they need to improve their condition.

To see Handicap International's work to raise awareness about Ebola, and see people with disabilities and other vulnerable individuals included in response activities, please visit here.

This post is part of a series produced by The Huffington Post and the NGO alliance InterAction in celebration of #GivingTuesday, which will take place this year (2014) on December 2. The idea behind #GivingTuesday is to kickoff the holiday-giving season, in the same way that Black Friday and Cyber Monday kickoff the holiday-shopping season. We'll be featuring posts from InterAction partners and others all month in November. To see all the posts in the series, visit here; follow the conversation on Twitter via #GivingTuesday and learn more here. For more information about InterAction, visit here.