Individual classical music events can be thrilling, thought provoking, beautiful, moving, or any combination of these and many other qualities, but they can't always be described as important in terms of their broader cultural significance. After so many performances of Beethoven's Ninth Symphony, for example, this revolutionary work has become so familiar to us that its radical message of universal brotherhood is more likely to strike listeners today as a too familiar backdrop for television advertisements than as an urgent call to social justice.

But once in a while a classical music event is important in a way that most "ordinary" people would recognize. I felt this, for example, when I watched John Adams's Doctor Atomic, at the Metropolitan Opera last season. Here the story of the father of the atomic bomb, J. Robert Oppenheimer, depicted through Adams' rasping, menacing as well as lushly beautiful score brought vividly to life the reality that we all still live on the edge of an existential precipice, whether the threat of annihilation comes in the form of an intercontinental ballistic missile or the wrath of a terrorist.

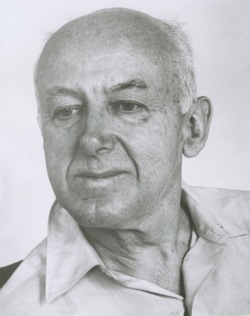

This Friday's concert by the American Symphony Orchestra and its music director, the indefatigable Leon Botstein (both clients of our company), is one I'd also describe as important beyond its musical significance. The program will feature six works by a single American composer: Henry Cowell (1897-1965). Musically speaking it's an important concert because although Cowell, pictured at right, is a seminal figure in 20th Century American music (as a composer, but also as an experimenter, teacher, theorist, pianist, and impresario), his works are rarely performed.

Botstein, who has been described by the New York Times as "a tireless champion of musical rarities" - and even more colorfully, by the now defunct New York Sun, as America's musical "Lewis and Clark" - fills each and every program of the American Symphony Orchestra's annual six-concert series at Lincoln Center - next season they move back to their original home, Carnegie Hall - with works that even the most seasoned music-lover have never heard before. But the Cowell concert is special even by his, and the orchestra's, standards, not least because the championing of American music has long been so important to the core mission of the ASO.

Critic Justin Davidson summed up the musical significance of Cowell in his "editor's choice" pick for the concert in the new issue of New York magazine:

The prolific American, who died in 1965, was a one-man melting pot for Irish folk songs, Chinese opera, Indian ragas, Japanese shakuhachi flute music, and avant-garde techniques like playing the piano with one's elbows. The generous American Symphony Orchestra program includes two symphonies, two New York premieres, and one of the most esteemed harmonica-and-orchestra concertos ever written.

Davidson didn't have room to mention that Cowell, who was born in Menlo Park, California, was a pioneer in what would later become the West Coast school of American composition. Far away from the still-strong influence of European music, Cowell consciously and subconsciously absorbed influences of Asian music, a seminal moment in the long-term development of American and even world music. The great avant-garde American composer John Cage called him "the open sesame for new music in America."

But it's Cowell's biographical story that pushes this concert into the realm of serious social importance for me. In particular, the impact of his being imprisoned in 1936 - in the notorious San Quentin State Prison, where he served four years of a 15-year conviction - for having homosexual relations with a consenting adult.

A few weeks ago I read in horror that the death penalty was being debated in Uganda as a way to deal with homosexuals, and I don't know enough about the subject to list the number of countries around the world who hold gay people in such utter and indefensible contempt. The more things change, the more they stay the same. And that's so right here in America as well, where friends from places outside New York City have told me that the kind of openness I share in public with my partner Brian, whom I have lived with now for 15 years, would never be tolerated in their hometown.

"You wouldn't want to hold Brian's hand walking down the block in front of my house - you'd get bashed for sure," is something I've heard not that long ago. Sadly, more than a few people are gay-bashed right here in New York City; stupidity, ignorance and hatred clearly know no geographic boundaries. Compared to the threat of such senseless violence, the indignity many gays feel at not being able to get married (in most states) seems strangely mild by comparison (I might as well throw in another pet peeve while I'm letting this all hang out: checking that box marked "single" my taxes or a health form, even though I've been in a dedicated relationship longer than many of my heterosexual friends).

So I've been thinking a lot about Henry Cowell this week, wondering how and if I would have survived, as he did, four years in prison for the crime of being myself. (Miraculously, Cowell continued to compose there, teaching his fellow inmates and even directing the prison band.) True, Cowell was pardoned, but people who knew him said he was a different man after his release from San Quentin, both as a person and as an artist. Formerly a passionate advocate of progressive (read "left wing") causes, Cowell sought afterwards to "keep a low profile" when it came to his political beliefs and hopes for social equality. Even his music, some observers noted, became less adventurous. Learning about all of this as our company worked to promote this concert, I couldn't help but wonder how many fine young boys and girls, and older men and women for that matter, will be less than they should be because of the persistent presence of bigotry - some of it still quite socially acceptable - towards gays?

Botstein's program book for the concert is available online and very much worth reading, not only as an introduction to Cowell and his music, but also for some of it's astute observations about the contradictions in America's cultural identity and aspirations. I finish this post with this short excerpt from those notes, along with thanks to Botstein and the orchestra for giving Cowell a substantial and long-overdue moment in the sun:

For all of America's celebration of its own love of invention and innovation, there has been a dark side to American cultural life: an enormous pressure to conform, the rule of a marketplace that is intolerant of genuine individuality and dissent, and a risk-averse anti-intellectualism derived from mistrust, isolationism, and commercial interest. Henry Cowell's career and music have consistently tripped the wires of all of these negative attitudes. As a result, for the last fifty years, his music was deprived of the hearing it deserved except in a small community of devoted advocates. More exposure is necessary to permit a reasonable assessment of the worth of his many compositions.

Leon Botstein in rehearsal with the American Symphony Orchestra (courtesy ASO)