Below is a speech I gave last year at a high school where students raised funds to help flood victims in central Vietnam. As the 40th anniversary of the end of the Vietnam War is coming up this April 30, 2015, I am posting it to commemorate the date. It will also mark my 40th year in America, having fled Vietnam as a child two days before the war ended.

I struggle to figure out what exactly to say today about Vietnam and the experiences that we all carry. My relationship with it remains complicated, and it is one with so many contradictions and without any final resolution. My Vietnam experience keeps on changing with the time.

I left Vietnam at 11 at the end of the war. We lost everything when we came to America. We started over from the bottom. There was a period in which we lived as impoverished exiles, sharing an apartment with two other Vietnamese refugee families at the end of Mission Street where San Francisco ended and the working-class neighborhood of Daly City began. We struggled for some time to make it to the middle class. There was a time when we were wrecked with losses and longings.

Vietnam, as some of you who are old enough to remember know, was never an easy-to-quantify topic, and a hard-to-frame story. The issue of Vietnam keeps changing, but as a writer and as someone who came from that country, I wonder if in so much writing that involves the word "Vietnam" we really are talking about the same country at all.

Take these few headlines in the news over the last couple of years:

- CNN: "Afghanistan haunted by ghost of Vietnam"

Often times when we mention the word "Vietnam" in the U.S., we don't mean Vietnam as a country. Vietnam is not Thailand or Malaysia. Its relation to the U.S. is special: It has become a vault filled with tragic metaphors -- it stands for American loss of innocence, of tragedy, legacy of defeat, and failure. For the first time in our history, Americans were caught in the past, haunted by unanswerable questions, confronted with a tragic ending.

So much so that my uncle, who fought in the war as a pilot for the South Vietnamese Army, once observed that "when Americans talk about Vietnam, they really are talking about America."

"Americans don't take defeat and bad memories very well," he added. "They try to escape them," he said in his funny but bitter way of his. "They make a habit of blaming small countries for things that happens to the United States: AIDS from Haiti, flu from Hong Kong or Mexico, drugs from Columbia, hurricanes from the Caribbean."

Then there's my father, who only talks about the Vietnam of wartime after a few drinks. When he gets drunk, his memories go back to the time when he was a big shot, a warrior, when he fought battles and won, a time when he was still full of vigor and promises. But he couldn't talk about the aftermath, about losing and the end and ensuing humiliation and the horrible losses. Of his comrades and his own brother sent to reeducation camps. Of the soldiers he left behind when he escaped.

He can only go further backward to a time before the war was lost. He holds so much anger still on what happened to Vietnam, to his comrades, that he, like so many of his generation, hasn't been able to go past vehemence, hasn't been able to make peace with the past.

I've been back to Vietnam many times. And as I moved out of my father's point of view, away from his shadows, I find that there's always new ways of looking at that country.

Some years ago, for instance, I went back to Vietnam to participate in a PBS documentary called My Journey Home, and I did the touristy thing: I went to Cu Chi Tunnel, in Tay Ninh Province, bordering Cambodia, a complex underground labyrinth in which the Viet Cong hid during the war many years ago.

Cu Chi Tunnel

There were several American vets in their late 60s there -- they fought in Vietnam and lost friends. They were back for the first time. They were very emotional. A couple of them cried after they emerged from that visit. One Vietnam vet wept and said that, during the war, he "spent a long time looking for this place and lost friends doing the same."

Yet the young Vietnamese tour guide, born after the war ended, did not see the past: She has a dream for a cosmopolitan future. She told me that it was tourism that forced the Vietnamese to dig up the old hideouts. Then, in a whisper, she said, "It was a lot smaller back then. But now the New Cu Chi Tunnel is very wide. You know why? To cater to very, very fat Americans."

She crawled through the same tunnel with foreigners routinely, but she emerged with different ideas. Her head is filled with the Golden Gate Bridge and cable cars and two-tiered freeways and Hollywood and Universal Studios. "I have many friends over there now," she said, her eyes dreamy, reflecting the collective desire of Vietnamese youth. "They invite me to come. I'm saving money for this amazing trip." If she could, she told me, she would go and study in America.

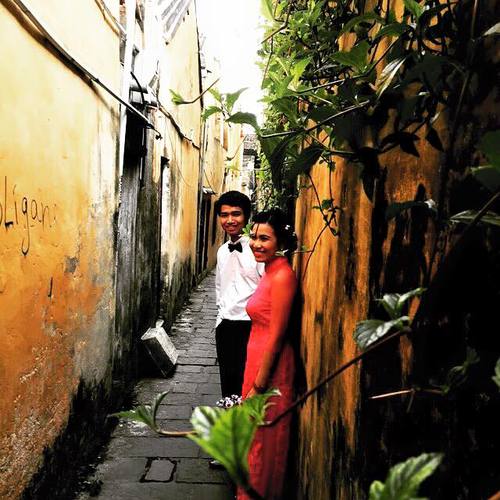

Vietnamese couple getting married in Hoi An, Vietnam.

So there I was, standing at the mouth of the tunnel, and thinking, in the end, there may never be final conclusion about that war.

There's the northern Vietnamese version of that war, where they liberated the south and saved those in the south from American imperialism. There's the version that we exiles tell in which the date marks the day we lost a country. There are plenty of stories of Vietnamese fleeing from oppression as boat people. Tens of thousands more were sent to reeducation camps. There are stories of young men fleeing from a war in Cambodia in which the Vietnamese were the imperialists. There are of course the stories the American veterans coming back to look at their losses and to make peace with the past.

And here was a young woman, born after the war ended, who looked at a tunnel that was the headquarters of the Vietcong, and what did she see? The Magic Kingdom. The Cu Chi tunnel leads some to the past, surely, but for the young tour guide it may very well lead to the future. Vietnam is indeed a country full of young people, and it more than doubled since the war ended, reaching over 92 million today. "I have many friends over there now," she said, reflecting the collective desire of Vietnamese youth. "They invite me to come. I'm saving money for this amazing trip."

Which is to say, the Vietnam War was a war with so many sides, and it's complicated by multiple points of view. In that sense when we talk about Vietnam, we should not simplify but expand toward the multitudes, so much so that it becomes the story of people, of human beings rather than some purported metaphor for tragedy.

* * *

My own story is that, through the years, I made my own peace with it. It has taken me a long time to come to the realization that for those whose lives have been inordinately altered by forces of history, the personal is to the historical is the way brooks and rivers are to the sea. James Baldwin's riddle is rhetorical, after all, when he asked in one piercing essay, "Which of us has overcome his past?" and promptly answered in another: "People are trapped in history and history is trapped in them." But with due respect, one can chase Baldwin's grim discernment with N. Scott Momaday's astute counsel: "Anything is bearable as long as you can make a story out of it."

The more mature response to one's tragedy is not hatred nor resentment but the spiritual resilience with which one can, again and again, struggle to transcend one's own biographical limitations. History is trapped in me, indeed, but history is also mine to work out, to disseminate, to discern and appropriate, and to finally transform into aesthetic self-expression. So I write. And write. And write.

And it is in stories about Vietnam, in looking at its current needs and its current problems, and trying to offer some insights, that I find my way home.

And I am not alone.

View of the new Saigon

A young Vietnamese-American friend of mine from Los Angeles, whose sister was killed by Thai pirates while escaping Vietnam, recently returned to Saigon, where she is now a thriving entrepreneur. Another, the son of a colonel who spent 14 years in reeducation, spent his honeymoon in Vietnam, despite his dislike of the Hanoi regime. Yet another friend, whose father was governor of Hue and who was in solitary confinement under communism for years, well, he came back, wrote a book and now owns a popular bar in Hanoi.

My cousin, whose family was robbed of everything, fled to France and has returned and married a local woman, raised a family, and sells French wines. He's prospering where his father once suffered in its malaria-infested reeducation camp. That was, in a sense, his best revenge.

Another friend went a step further: She was forced to escape as a boat person with her family in the late '70s, has returned with money raised in Silicon Valley to help create a program to prevent impoverished families in Mekong Delta from selling their children to traffickers. She's changing the destinies of many others like her for the better.

Having lost the war, these people have emerged as the victors of the peace.

They've managed to remake themselves and go on with their lives, and more important, by refusing to let rage and need for vengeance dominate their hearts, some have become active agents in changing Vietnam itself.

So in the end only lives lived every day matter, only when one tries his best to influence and create a better future all of mankind matters. Only when one addresses the needs and sufferings of the living that the ghosts of the past would be appeased. And only when one looks at Vietnam not through the view that's rooted in historical vehemence but through the view of human kindness does the country open itself up.

A while back I heard the Dalai Lama said this to an American audience:

"If you want others to be happy, practice compassion. If you want to be happy, practice compassion."

It is easier said than done, I know. Rage and sadness sometimes flare up in me, and it feels as if nothing in the world could ever douse it.

"If you want others to be happy, practice compassion. If you want to be happy, practice compassion."

That is if we want see Vietnam, or for that matter any country beyond its geopolitics, its historical relationship with the U.S., then we need to open our heart. If we want to see human liberty, then we'd best try to uphold human dignity. And if we want to find peace, we must find a way to forgive others, and just as important, if not more, ourselves.

It's what I, despite the sadness and burden of memories, strive for. And in the face of human suffering, I hope it's what we'd all strive for.

Andrew Lam is an editor with New America Media and the author of Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora and East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres. His latest book, Birds of Paradise Lost, a short-story collection, was published in 2013 and won a Pen/Josephine Miles Literary Award in 2014.