For every Syrian who escaped the civil war in his or her homeland by crossing international borders, there are three more displaced within the country. Those who manage to leave become refugees. Those who stay behind remain invisible. But they are part of a growing population of refugees that are often without international support, a sub-group of people whose basic needs are rarely addressed by the global community: the internally displaced.

Since the civil war started in April 2011, 2.2 million Syrians have fled across the borders, the majority to Jordan, Lebanon, and Jordan. But according to the USAID there are at least 5 million internally displaced people who failed to do so and are in dire need of humanitarian assistance but largely remain out of international reach.

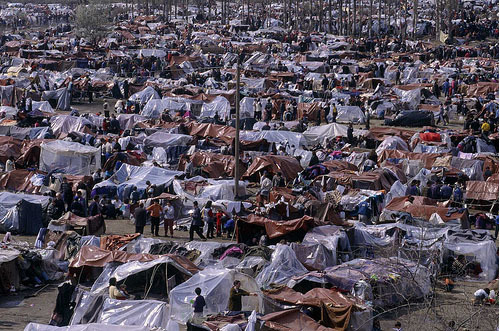

All who are robbed of home and hearth suffer, of course. But those who escaped the fighting in their homelands by fleeing abroad at least managed to survive, even if they have to subsist in tents and ramshackle huts and depend on charities and donations. Some receive the world's sympathy and media coverage. A rare few even found asylum in the West.

By contrast, those who are internally displaced fare much worse, as they become truly dispossessed. They fail to cross an international demarcation and thereby don't legally qualify as refugees. Instead of receiving international protection and media coverage, many remain invisible and live in constant fear. As in the case of Syria, with the civil war restricting international media coverage and assistance, very little protection for IDPs can be had.

A United Nations report "Guiding Principles on Internal Displacement" defines internally displaced persons (IDP) as "persons or groups of persons who have been forced or obliged to flee or to leave their homes or places of habitual residence, in particular as a result of or in order to avoid the effects of armed conflict, situations of generalized violence, violations of human rights or natural or human-made disasters, and who have not crossed an internationally recognized state border."

It is the "natural or human-made disasters" part of the UN definition -- which itself is not legally binding -- that makes the number difficult to quantify and monitor. Do the millions of roaming Chinese within the country because of industrial pollution that's devastated their agricultural land or displacement by a government building project count as Internally Displace people? And what do we make of Japanese citizens forced out of Fukushima region? How about those who fled from environmental degradation and drought? There is just no easy way to quantify this population of the displaced.

On top of the current news curve is the story of the victims of Haiyan typhoon in the Philippines. Some 800,000 are reportedly homeless, and conditions worsened as many are living without support in hard to reach area. But they at least are garnering world sympathy and news coverage.

For the majority of the displaced population, their stories aren't told, and invisibility is their curse. But their numbers are increasing. According to the UNCHR there are 26.4 million internally displaced people in the world in 2011. But some organizations estimate that the actual number of IDP is easily twice the number of internationally recognized refugees, if not triple that amount. The figure can fluctuate due to the sudden outbreak civil war or a natural disaster such as an erupting volcano, tsunami or earthquake.

Distributions of food and medicine vary from place to place, and IDP protection depends on where they find themselves and which country they are in. Haiti is but a quick jump over from the United States and after the earthquakes in 2010, food and supplies and media coverage came relatively quickly -- if chaotically -- for earthquake victims. But after years of civil war in Darfur, hundreds of villages have been destroyed, 400,000 have died, and 2.2 million are now permanently displaced and many facing starvation and ongoing violence. It's a humanitarian crisis in which the international response is shockingly slow and ineffectual, and world attention is at best sporadic and the international community falls into what is popularly known as compassion fatigue.

It may explain why there's little coverage for the millions displaced in The Democratic Republic of Congo, where 45,000 people continue to die each month, and more than 6 million people have died from long drawn out war and famine? And we know little about the hundreds of thousands of Muslim Rohingya population in Rakhine state who are robbed of home and hearth due to religious persecution in Buddhist majority Myanmar? Unless they drowned at sea trying to escape the country, as in the case of the 50 refugees last week, their stories remain largely untold. In Iraq, as of the end of 2012, there are 2.1 million people living in protracted displacement, their world unraveled because of the US occupation and inter-ethnic strife. In North Korea, the suffering and starvation of a large number of people remain mostly unknown.

Refugees and IDP are essentially the same. Both groups are coerced or compelled to flee in fear for their lives and security, but those who crossed internationally recognized state borders fall under systematic protection and assistance under existing international treaties, while those who don't are entitled to little, and often garner little international attention. Pope John Paul II once called the plight of refugees "the greatest tragedy of all human tragedies" and "a shameful wound of our time." In the 21st century, that wound has festered and gangrened. How effectively we as an international society address it will largely determine the future of our global society. For all refugees' plight should challenge our conscience, as silence and indifference constitute the sin of omission.

Andrew Lam is an editor with New America Media and the author of three books, "Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora," "East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres," and his latest, "Birds of Paradise Lost," a collection of short stories about Vietnamese refugees struggling to rebuild their lives in the Bay Area. It recently won the Josephine Miles Literary Award and is now available on Kindle.