Note: I wrote the essay below almost two decades ago, at the beginning of my life as a writer. It is collected in my first book Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora which won a Pen Award in 2006, and is anthologized widely over the years. A popular assignment in high schools and colleges, it still holds up well, I think, despite the years. Grandma is long gone but as Mother's Day approaches, here it is, available online finally, for those who have fond memories of their grandmothers like I do.

When someone dies in the convalescent home where my grandmother lives, the nurses rush to close all the patients' doors. Though as a policy death is not to be seen at the home, she can always tell when it visits. The series of doors being slammed shut reminds her of the firecrackers during Tet.

The nurses' efforts to hide death are more comical to my grandmother than reassuring. "Those old ladies die so often," she quips in Vietnamese, "everyday is like New Year."

Still, it is lonely to die in such a place. I imagine some wasted old body under a white sheet being carted silently through the empty corridor on its way to the morgue. While in America a person may be born surrounded by loved ones, in old age, one is often left to take the last leg of life's journey alone.

Perhaps that is why my grandmother talks mainly now of her hometown, Bac-Lieu, in the Mekong Delta. Its river and rice fields are vivid in her retelling. Having lost everything during the war, she can now offer me only her distant memories: life was not disjointed back home; one lived in a gentle harmony with the land; people died in their homes surrounded by neighbors and relatives. And no one shut your door.

So it goes... The once gentle, connected world of the past is but the language of dreams. In this fast-pace society of disjointed lives, we are swept along and have little time left for spiritual comfort. Instead of relying on neighbors and relatives, on the river and land, we hope the health care system won't let us down in our old age. Instead of going to temple to pray for good health, we pay life and health insurance.

My grandmother's children and grandchildren share a certain pang of guilt. After a stroke that paralyzed her, we could no longer keep her at home. And although we visit her regularly, we are not living up the filial piety standard expected of us the old country. My father silently grieves and my mother suffers from headaches when they visit. (Does my mother see herself, I wonder, in such a home in a decade or two?)

Once, a long time ago, living in Vietnam, we used to stare death in the face. The war, in many ways, had heightened our sensibilities toward living and dying. I saw dead bodies when I was five after a battle erupted near my house during Tet offensives. I remember holding on to my great uncle's hand as we watched blue bottle flies gathered on the wounds of the dead. If I was afraid, I now feel appreciative of my Great Uncle's gesture. I could look at the horror of war in the face.

Though the fear of death and dying is a universal one, Vietnamese did not hide from it. We prayed daily to the dead at our ancestral altar. We talked to ghosts. Death pervaded our poem, novels, and sad ending fairy tales. We dwelled in its tragedy. We know that terrible things can and do happen to ordinary people.

But if agony and pain and suffering are part of Vietnamese culture, admittedly, to be point of being morbid at time, pleasure is at the center of Americans'. While Vietnamese holidays are based on death anniversaries of famous kings and heroes, birthdates of presidents are celebrated here.

American popular culture treats death with humor. People laugh and scream at blood-and-guts movies. Zombie movies are the rage. The wealthy sometimes freeze their dead relatives. Cemeteries are places of business, complete with colorful brochures. There are, I saw on TV the other day, drive-by funerals in some places in the mid-West where you don't have to get out of your car to pay your respects to the deceased.

That America relies upon the pleasure principle and happy endings in its entertainments does not, however, assist us in evading suffering. Americans tell their kids everything will be Okay. American children are spoon-fed undaunted optimism and happily ever-afters then grow up to confront realities like divorce, domestic violence, drugs, broken homes, failed politicians. No wonder so many teenagers, as if chasing the saccharine of childhood narratives, seek solace in the pages of Stephen King and Anne Rice, horror's king and queen. These days the little train that could carries very few passengers.

Then there is the loneliness of old age. When one visits the convalescent home the suffering of the old is self-evident. There is an old man, once an accomplished concert pianist, now rendered helpless by senility and arthritis. Every morning he sits on his wheel chair and stares at the piano in the cafeteria. One feeble woman in her late 90s who outlived all of her children keeps repeating: "My son will take me home. My son will take me home." One smells death in the air even if one cannot see it there. One hears death in the moans and groans of those in pain. Take a look down the hall. There are those mindless bedridden bodies kept alive through a series of tubes and pulsating machines.

Last week on her 83rd birthday I went to see my grandmother. She smiled her sweet sad smile.

"Where will you end up in your old age?" she asked.

I was taken back by the question. The memories of the monsoon rain and tropical sun and a world of clanship and insular network of people came back to mind. Not here, not here, I wanted to tell her. But the soft moaning of a patient next door and the smell of alcohol wafting from the sterile corridor brought me back to reality.

"Anywhere is fine, grandma," I told her instead, trying to keep up with her courageous spirit. "All I'm asking for is that they don't' shut my door."

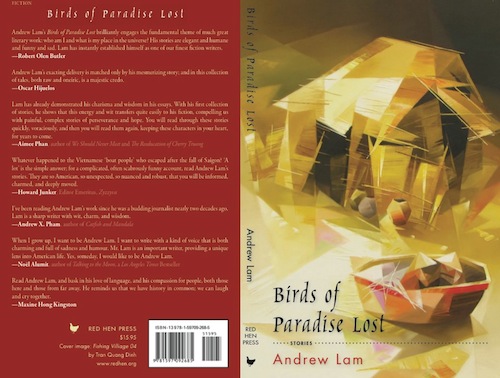

Andrew Lam's latest book, Birds of Paradise Lost, a collection of short stories about boat people who remade themselves in America's West Coast.

Andrew Lam is editor and cofounder of New America Media, an association of more than three thousand ethnic media outlets in the United States. He is the author of Perfume Dreams: Reflections on the Vietnamese Diaspora, East Eats West: Writing in Two Hemispheres, and most recently, a collection of short stories, Birds of Paradise Lost.