F. Scott Fitzgerald has been imagined, literately, to bits since his celebrity began in 1920, when he was 23. The New York Times gushed, that spring, about Fitzgerald's first novel, This Side of Paradise: "The glorious spirit of abounding youth glows throughout this fascinating tale. Amory, the romantic egotist, is essentially American[.]"

Essentially American is still Fitzgerald's tag-phrase, and it suits him. The beautiful young author of Paradise has been dubbed A Great - and perhaps The Great - American Novelist since his third novel, The Great Gatsby, posthumously granted Fitzgerald that status. We still think of him chiefly as Gatsby's author, though, by the end of his life, he was not often thought of in the world of readers and writers at all.

Fitzgerald spent the end of his life in Los Angeles, where, from 1937 until his untimely heart attack at 44, in December 1940, he tried to make it as a Hollywood screenwriter. He never did so, though he worked on some hits like Gone With The Wind (1939). Reprieved from screenwriting, ironically, by his ill health, Fitzgerald was writing a book about a dying Hollywood producer, his life and loves, at the time of his own death.

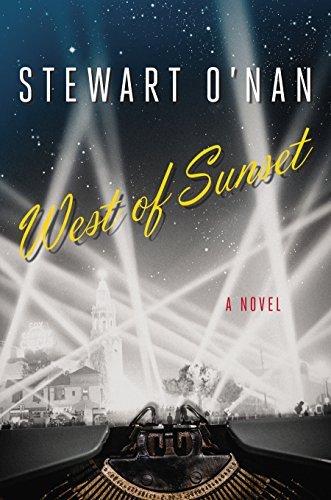

In his new novel West of Sunset, Stewart O'Nan imagines Fitzgerald's last years with passionate intensity (and I do not use the phrase with W.B. Yeats's negative edge). Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald have long been subjected to fictionalized autobiography, in poor Zelda's case less historical fiction than what I call, with dismay, hysterical fiction. Such novels often claim to be thoroughly researched - a paradoxical claim for fiction. Some are well-written and engaging, and some are awful, simply capitalizing on the golden Fitzgerald name. West of Sunset does not invoke that name. Its cover does not feature famous faces, but evokes Hollywood of the Golden Years, foregrounded by an old typewriter (Fitzgerald hand-wrote, but, in Hollywood, appreciated the plentifully-availably typists). Within, O'Nan has made not only a good novel, but a sensitive, sad tribute to a writer he clearly loves.

Why Fitzgerald, I asked him. "It was the Golden Age of the studios, maybe the high water mark of American glamour. What would it be like to work on the lot at MGM and hang out with Scott Fitzgerald and Dorothy Parker and their friends at the Garden of Allah? So, basically, to fulfill my curiosity." Yet O'Nan spends most of his time not in dialogue and conversation, but inside Fitzgerald's head, imagining and setting down his thoughts. To write Fitzgerald joking around with Humphrey Bogart is something public. The private is what's most difficult. How can you presume, really, to think what "Scott Fitzgerald" thought, to take the reins from a painstakingly professional writer and give him his "own" words? Even if your Fitzgerald is a fictional character, and it's a novel, this is something to approach with trepidation.

Says O'Nan, "I wanted to get closer to him and find out what was going on with him, what was on his mind. As best as I could, I wanted to feel how it felt to be him, to deliver his emotional world to the reader. I figured if I cared about him and found him interesting, so would the reader." The caring is the strong suit here; plenty of people find Fitzgerald, the actual writer, interesting. But how to make one's own manifestation of him interesting?

O'Nan read Fitzgerald's works and letters to prepare himself. He re-creates letters from Scott, Zelda, and Scottie in his novel, and explains why matter-of-factly, and with humor: "The letters I composed are woven out of the vocabulary the three of them use, mimicking their various tones. The letters also help give some variety to the surface of the prose, and add a dash of intimacy only the first-person can provide. So they're a risk that offers a reward....They were fun to write in the way climbing farther out on a limb is fun." The limb never breaks beneath O'Nan, or us. Occasional linguistic slips - as when Mayo Methot Bogart calls Sheilah Graham a "gold-digger with the bazongas" - can jar; gold-diggers have been with us for centuries, but bazongas first appeared around 1972. This is hardly fatal, and despite the sad trajectory of the story he is following, you feel the fun O'Nan is having in making up his own details and scenes.

West of Sunset begins in North Carolina, as Scott is leaving for Hollywood on a contract with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer that will enable him to pay his daughter's school fees and wife's hospital bills. Zelda, a character drawn here with sensitivity and real affection, remains behind in Asheville, but is - as she was, even across a continent - a constant presence in Scott's life. His visits back to see her are moving and disastrous, largely because of the reminders of what has been lost: that they will never be so young again.

Sheilah Graham, the Hollywood columnist who became Fitzgerald's lover in 1937, figures in West of Sunset, but not, particularly, as the center of Fitzgerald's attention. In her several memoirs of her three-and-a-bit years with Fitzgerald, Graham, predictably, made herself just that. (For reference, no biography covers Graham's whole life; Rachel Syme's forthcoming book will remedy this.) O'Nan describes his character of Sheilah as, appropriately, "seen through Scott's eyes, and at first she's a mystery to him, an obsession and an object of romance he wants to possess. He admires her strength and confidence, but, riddled with self-doubt and sickness, fears it as well. He comes to understand that, like him, she's her own person, self-made, ambitious and capable."

In West of Sunset, Fitzgerald experiences his first cardiac episode in bed with Graham, making love, commenting after, "You're going to wear me out." I winced at what seems an invasion of privacy; recall the way Fitzgerald himself wrote sex: "Daisy comes over quite often - in the afternoons." Or, if you need more detail, here: "Then, with her knees she struggled out of something, still standing up and holding him with one arm, and kicked it off beside the coat. He was not trembling now and he held her again as they knelt down together and slid to the raincoat on the floor." Yet moments in West of Sunset more often made me smile, ruefully and sympathetically, when they sliced into the personal: Fitzgerald hiding empty liquor bottles in Bing Crosby's trash can; his eager delight in a big star knowing his novels; his lack of enthusiasm for the idea of showing Sheilah his old Manhattan haunts because "it seemed a betrayal of Zelda. At the same time he couldn't discourage her without hurting her feelings, and played along, feigning anticipation."

The amount of feigning that Fitzgerald was obliged to undertake, on all fronts in his life in Hollywood, underpins West of Sunset - and this part of the novel is all too authentic. It is painful and (to use a favorite word of Fitzgerald's) nostalgic to read even imagined scenarios of what Fitzgerald endured, like his own fictitious screenwriter Pat Hobby, as he tried to get through. As O'Nan nears the inevitable end, you wish he might indeed repeat the past - rewrite the past, rather, and make fiction fact. Let's have Fitzgerald live, to the age of his own mother, say. Let him complete "The Loves of The Last Tycoon," or whatever he'd have chosen to call it, and half a dozen more novels besides. Let him make it all the way into the 1970s; see what he thinks of the '60s, of our music and wars and men on the moon; see how he likes being a grandfather to four.

West of Sunset ends, instead, as it must, with Fitzgerald's death. No spoiler alert is necessary. O'Nan closes with Fitzgerald's own last imagined thoughts as he dies, split between real memories and the self-created: a flashback to St. Paul and his boyhood, with "his mother combing his hair with her fingers, his father's whiskery jaw" - and Monroe Stahr, the last tycoon, "standing to one side like a kindly spirit." Fitzgerald wasn't finished with living, or with writing, and these facts have made and keep him near-mythic, forever the stuff of fiction himself.

I finished West of Sunset compelled to reread, yet again, The Last Tycoon. O'Nan subtly weaves details from Fitzgerald's unfinished novel into his own - a thunderstorm, a sculpture's head, moments that you only realize later have happened for his character Fitzgerald's imaginative benefit, and that add to the already-thick layers of creativity in West of Sunset. West of Sunset made me miss Fitzgerald when I was done, and I'm grateful for that feeling.

Anne Margaret Daniel is working on a book about F. Scott Fitzgerald.