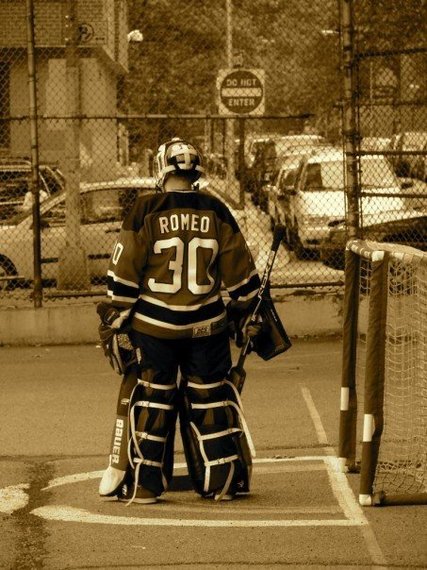

Dressing from left to right, I slide into my equipment, pulling the straps of my leg pads tight, taking the time to leave enough room to allow for better rebound control. I pull on my chest protector, strapping it against me, around me. I tug my jersey over my head, fitting my arms through the sleeves and adjusting the way it lays over my gear. As I walk from the arena locker room to the rink, I stop on the way. I kiss my husband, and skate onto the rink surface. It's game time.

As a kid growing up in the Catskills, I loved hockey. I lived for the times when Pete Naples, our high school gym teacher, would choose floor hockey as our sport. I would tell my teachers I'd need to be excused for a viola lesson, and would show up in a random gym class, running immediately to the net. I bought a stick, and kept it at school for the express purpose of harnessing my craft. Either my teachers never caught on, or more likely, they were doing what teachers tend to do, supporting a student's passion. Fifteen years later, no one was surprised I married a teacher.

When I started at college, I had realized that I was gay, and was starting to plant furtive steps into the world of my own skin. And that skin very much included hockey as a way that I identified. I was gay, yes, absolutely and unequivocally. But it was also with that same assuredness that I saw myself as a goalie. It's who I was, not a choice but a hard-wired, reality-based, dream-fulfilling, butterfly-inducing aspect of my very being. I can recall my first kiss with as much vividness as I recall my best glove save, a two-pad stack, sliding across the crease and wind-milling my glove into the top corner of the net to deny the glory to a shooter who was sure he had scored.

It was at Seton Hall, a private Catholic University, that I learned who I was, and the man I discovered could be neither Catholic, nor private. I was pulling my gear back to my dorm room when I found that my door and surrounding walls had been vandalized with anti-gay graffiti. In red permanent marker, someone had written faggot, and queer and homo. And so there I stood for awhile, my goalie stick leaning against the door frame, allowing the rouged epithets to scream past my eyes, rip through my chest, and fill the cavern of insecurity inside my 17-year-old body. And I waited to see if anything took hold, if in some way the iron could brand. And it's the same boy from Pete Naples' gym class who opened the door then, pulled his goalie gear into his bedroom, and cried.

In 2002, when marriage equality was a term still yet-to-be, the world felt different. Coming out was still a big deal. You could count on one hand the number of openly gay celebrities, and on no hands the number of openly gay athletes playing sports. I didn't have an athlete to emulate who had navigated this world. It was up to me to figure myself out.

After a pair of tumultuous years at Seton Hall, where I sued them for the right to assemble a gay-straight alliance, I needed to leave. I was feeling really low about myself, about the world and the ways it treated boys like me. The only escape for me was when I was in my gear, stopping pucks. I could push away all the noise, all the distractions, and focus on stopping a tiny rubber puck, flying through the air at 80 miles per hour. Life, stripped down to a piece of vulcanized rubber and the will to stop it.

Hockey became my air. When I was going to the arena to watch my New Jersey Devils play, I was just another one of the 17,000 faces in the crowd, no different. No better, and certainly no worse. I'd watch Martin Brodeur play, his cool and collected approach to goaltending infusing his team with a calmness I had never known in my own game. I worked on that, inside. I worked on allowing a stillness to fill me before games, to allow myself to only be in control of the things I could control. That approach started to become more effective in my personal life, and not just in my sports career. If I could be in control of myself, then in the act of knowing myself, I could be all I needed. If I allowed myself to only manage my own life, my own reality, then I could get to a place where I was enough, and could virtually shut out any negativity directed towards me as easily as I could direct a rebound into the corner boards.

And that's how I found my legs, connected, rooted, planted and firm.

Hockey players have fun with labels, whether you're a sniper, an enforcer, a stay-at-home defenseman, an agitator, or a plug. But it's goaltenders who have the opportunity to take things a step further, to showcase their own personality through their equipment, from the NHL right on down.

Every goalie has his gear guy, the dude who takes care of his equipment, and makes sure he's in a setup that not only keeps him safe, but looks sharp. My guy is Mike Urbano, and he's the manager of GoalieMonkey, a division of MonkeySports, that truly is the end-all for goalies who are looking to get new gear, whether it's pre-made or custom designed. I can't even describe to you, but the world of goalie gear is huge, with tens of thousands of people flocking to Facebook groups to ogle at each other's setups. It's an interesting world where men can pay compliments to another man on what he's wearing, and it's not weird. Almost seems like the way it ought to be, huh?

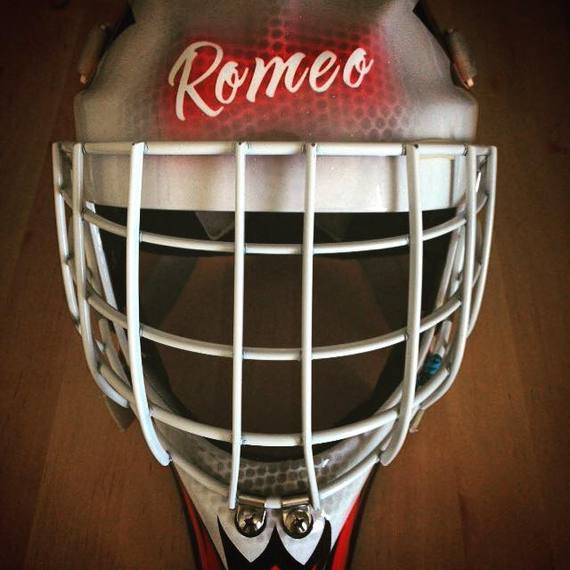

We get to represent ourselves with our equipment, but most especially with our masks. Goalie masks are a thing of absolutely beauty. For years, I had played in a helmet that was an exact replica of Martin Brodeur's helmet, the sincerest form of flattery. I felt such a connection to my sports icon, and to pull on the same bucket made me remember to mimic his approach.

But once I found myself in a more confident place, it was time for me to design a helmet of my own. I worked with Tony Jarrett of Masked Expressions for my first helmet, as well as for my most recent. My first helmet had nods to Martin Brodeur, my hometown, and a custom logo on top. It was orange and black, my high school colors, and I wore that bucket with every bit of pride and bravado I could. It was made just for me, in a time when I was still very much in the making of myself.

But now, I have a new helmet. On the back, you'll find references to my brother and sister, and their respective alma maters, as well as to my late Mom. You'll also see a wizard hat laid on top of a rainbow, with the initials D.S. on top, for my husband. That dorky, Harry Potter-loving husband of mine that I kiss, gratefully and proudly, in front of my teammates, before my games.

Because the world isn't changing, it has changed.

There are now organizations like You Can Play, that actively promote LGBT participation in sports; this is a lifeline for so many young gay athletes who may have felt marginalized, or under-represented.

Andrew Ference, the alternate captain of the Edmonton Oilers, helped launch Pride Tape, a roll of rainbow hockey tape, to help foster inclusiveness and an atmosphere of respect and support for GLBT athletes. In this way, hockey is a sport that is leading the charge, far beyond anything being done by the NFL, NBA, or MLS. The hockey community is at the very forefront of the push to welcome gay athletes into the fold, at all levels. We are good enough, just the way we are.

And that's just it. That's exactly it. I have walked with feet in both worlds, and watched the perceptions around me change. I have led by example, forging a path for myself in a world of my own creation, where a gay boy from the mountains of upstate New York can be just as good as anyone else, and on any given night, under the heat of the rink lights, maybe even a little bit better.

Because this boy who never thought he could? Who assumed the world would see him as less than? Well this boy is a man, and his team made him an alternate captain, to reflect his leadership on and off the rink.

And this man is a champion.

You don't have to sacrifice passion for identity, nor identity for passion. I have taken the parts of myself that scare me, and others, and worn them as a badge of honor in a changing world. I've worked hard to become a man my son can be proud of.

And so as I'm strapping my pads on, left to right, it occurs to me. The courage to live an authentic life is harder than any slapshot I could ever face. Stopping the voice inside of me that says "You're not good enough" is tougher than any puck I could stop. And for the thousands of saves I've made in my life, I've never stopped to look inward, to realize how much, in the end, it isn't me making the saves.

It's hockey that saved me.