Anne-Marie Slaughter's recent article in The Atlantic, "Why Women Still Can't Have It All," has kicked off a typhoon of debate across the country. Slaughter, the former director of Policy Planning for the U.S. State Department and longtime Princeton academic, has made waves with her decree that present conditions make it impossible to have both a satisfying work life and raise a family and that the feminist dream to "have it all" is out of reach. As Katie Couric stated in her panel with the author at the recent Aspen Ideas Festival, the article has struck a chord, opening the floodgates for discussion on a topic that affects the future of the American workforce.

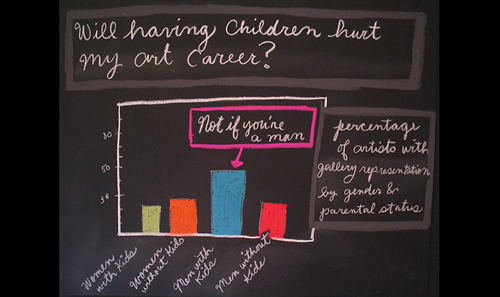

Jennifer Dalton, "How Do Artists Live?" (2006) / Courtesy the Artist and Winkleman Gallery, New York

What, we asked, about women in the art world? Does Slaughter's claim hold true in this field with so many powerful women, and are there other conditions specific to careers in art that haven't been addressed? ARTINFO reached out to high-achieving women in the arts with varied backgrounds and career paths, both mothers and non-mothers, with the hopes that a few would be willing to comment on their own personal experiences balancing work, family life, and the choices that have allowed them to pursue their goals.

We received an overwhelming response -- so overwhelming, in fact, that in another article we plan to publish the complete responses. Some clear themes emerged in the experiences of the women who wrote to us, however, and what follows is a selection of voices of those trying to manage what is by all accounts a difficult balancing act on the peculiar terrain of art.

FLEXIBILITY & SACRIFICE

Where does the drive to "have it all" come from, and at what cost? Lisa Dennison, chairman of Sotheby's North and South America agreed with Slaughter's contention that her generation had inherited some unrealistic expectations. "When I went to Wellesley College in the early '70s, a time in which feminist theory was our credo, we were 'taught' to be superwomen and that a career/family balance was absolutely achievable -- in fact, would be the norm for our generation," she said. "So my goal was 'to have it all.'"

Yet she also had learned to cope with the dilemmas of work and family life in a way specific to a career in the arts. "I tried to incorporate the family as much as possible into my world -- gallery-hopping on Saturdays, letting the kids run around Soho instead of the playground, and using my airline miles or spare bed in a hotel to bring an older child with me to places like Venice or London. I tried to make my world their world as much as possible."

But while for some blending family time with work hours was (somewhat) manageable, this wasn't the case with everyone we spoke to. Jane Cohan, director of press relations for James Cohan Gallery, explained how navigating round-the-clock gallery meetings and international art fair travel led her to compromise on career objectives so she could spend more time with her family. "For me, I choose to be the parent who flexes for the kids," she expained. "This meant that I found that I couldn't be effective in a sales position. Sales directors need to be at the gallery to greet clients whenever they drop by, be able to go out to dinner, and attend art fairs and openings with their artists."

While compromise changed her career path, Cohan reflected that her chosen field did ultimately allow her to negotiate a position of flexibility -- the thing Slaughter feels is culturally lacking. "I can look back at my work life over these years and count among them many accomplishments that I feel proud of, and I've had much career satisfaction. It's been a compromise. This is changing though now that my children are older, with one away at college now. I am able to participate in much more and take on more responsibility."

Bettina Prentice, founder of Prentice Art Communications, Inc., painted a picture that reflects a different generation of women who have embraced technology in aiding their ability to work remotely, and who do not try to separate work and family as much. She emphasized that overlap between different spheres often occurs. "My work and personal life are so intimately connected," she said, "though perhaps that is the nature of owning your own business." This final point may be especially true to the art world, where there is a large number of women that run their own enterprises -- from galleries to public relations firms, like Prentice's, to the "enterprise" of being an artist itself.

COOPERATION & CAREER PLANNING

Among the women we talked to, the consensus seems to be that such blurring of the lines between work and family is unavoidable. Still, a common feeling was cooperation and various forms of novel arrangements were needed to share the added responsibilities of having a family, and that sometimes creative careers provided room for such shared responsibility.

Doreen Remen, co-founder of the Art Production Fund, says she has had to be selective about events she attends, and organizes her time so that she can maximize efficiency while still having dedicated family time. But she also highlighted how having an understanding business partner was a big help.

The other half of the Art Production Fund, Yvonne Force Villareal, confirmed that the fact that Remen was also a mother provided her a form of support. "Luckily my business partner had children earlier in her career (they are off to college soon) while I had my first (who is 8) in my late 30s and now have an 18-month-old at home," she said. "We have naturally covered for each other, and made sure that children are the priority."

Dennison, for her part, cited her family's live-in nanny of 12 years as integral to providing consistency and stability for her children. But she also offered insight into Slaughter's key point about timing when planning a family and building a career. "I started on my career track as early as my sophomore year in college, and because I was married in my 20s and had two children in my early 30s, the 'sequencing' that Ms. Slaughter refers to was indeed a plus." She added, "It is good to start thinking about this early on, and it's important to find a mentor (or mentors) to help you navigate these difficult waters."

Even with these kinds of advantages, however, she acknowledged that it is nearly impossible not to make tough choices. "What I quickly grew to learn is that 'balance' is a relative term. Something always has to give - compromise and sacrifice are constant factors."

Antonia Carver, director of Art Dubai pointed to what she saw as a large hole in Slaughter's argument, particularly in the cosmopolitan art world: While mentioning new technologies and their ability to allow women to work remotely across the globe, Slaughter does not give particular attention to international perspectives on work and family life, wherein the term "having it all" may mean something entirely different.

According to Carver, the high proportion of women in top positions in the art world in the Middle East makes for a more supportive environment for working mothers, and women in the workforce in general. "Dubai in particular is a very career-oriented, entrepreneurial city: everyone has their mobile number on their business card, and the line between work and family time is very blurred -- something that's both positive and negative in the balancing act."

"HAVE IT ALL?"

For some, the greatest issue they take with Slaughter's article is in its headline, both with the definitive "Can't" and the expansive "Have It All." (It is worth nothing that in Slaughter's most recent reflection on the media sensation she reevaluates her use of the that phrase, which has driven many angry rebuttals.)

Artist Jennifer Dalton, who has in the past made art work devoted to this very subject (see the illustration of this article), took great issue with the titling, saying that "'having it all' is an offensive way to frame the problem. No one gets to have it all; using that phrase makes legitimate feminist goals of equal opportunity seem childish, absurd, and materialistic."

She adds, "What I don't like is her framing of women's choices as more fraught than men's because women inherently feel less comfortable working and spending time away from their children than men do. I respect that this has been her experience, but I haven't found it to be generally true for me or the other parents I know."

Mary Sabbatino, vice president of Galerie Lelong echoed Dalton's critique. "Why is this 'having it all'?" she asked. "Isn't it normal to want a personal and a professional life?"

Carver, similarly, was taken aback by way the problem was framed -- though she thought it did reflect a real social pressure. "Where we went wrong seems to be in the way that it was assumed that 'having it all' was a universal aspiration, and that the responsibility to achieve this should come from women themselves. It wasn't society that needed to change, but women who needed to try harder. So the weight of balancing work and family, and the challenge of physically 'fitting it all in' primarily fell to women."

SUGGESTIONS

There were also words of advice. Concretely, Dennison supports the idea that for round-the-clock jobs, like many in the creative field, there should be wider use of comp time like that instituted while she was working as director at the Guggenheim. "After you finished a three-week installation, or something enormous that kept you working 24/7, you would immediately take some comp time, to enable you to regroup and redress the balance in your life, and of course, have time with the family."

Villareal thought some well-placed policies could be of help. "Having some kind of a tax write-off on child care would be helpful -- a large majority of most working women's salaries go to paying for the beautiful care they are providing for their children whilst they are away contributing to the economy," she said. This, of course, is true for everyone, inside and outside the arts.

For her part, artist Natalie Frank points out the need to redress some historical art-world greivances -- specifically the well-known disparity between men and women in terms of who gets shown -- before taking about 'having it all.' "If women are at such a strong disadvantage in terms of representation in galleries and museums, sale prices, and visibility -- only a very limited story is being told." Greater gender equality when it comes to career opportunities would certainly also help make a difference for women who are working artists.

Still, there was a sentiment that the art world at least offered the support of some highly visible female success stories. "In the New York art world I am surrounded by amazing and inspiring women who have families and still hold some of the most important positions in the highest institutions," observed Cecilia Alemani, curator for the High Line. "I am thinking of Lisa Phillips at the New Museum, Nancy Spector at the Guggenheim, Sheena Wagstaff at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, and Anne Pasternak at Creative Time to name a few. I cannot speak on their behalf but I deeply admire them not only professionally but as women in leading roles in a very competitive and often male-driven realm."

-Alanna Martinez, BLOUIN ARTINFO

More of Today's News from BLOUIN ARTINFO:

Like what you see? Sign up for BLOUIN ARTINFO's daily newsletter to get the latest on the market, emerging artists, auctions, galleries, museums, and more.