At the age of 78, Foulkes is having his second big moment. The L.A. artist and musician showed with Ferus Gallery in the 1960s and enjoyed early recognition for quirky, detailed oil paintings -- an enormous cow, or rocks that sort of looked like people. He later moved on to more complicated mixed-media works, creating intricate scenes that brought together cartoon culture and self-portraiture as well as an ongoing series of grotesque bloody heads. When Scott Indrisek spoke with him, Foulkes had had a few recent pieces in last year's Documenta (13) exhibition, where he also sang and performed with his complicated, self-made musical instrument, dubbed the Machine. Next month a retrospective of more than five decades of his work comes to the Hammer Museum, in Los Angeles; it will travel to the New Museum, in New York, in June.

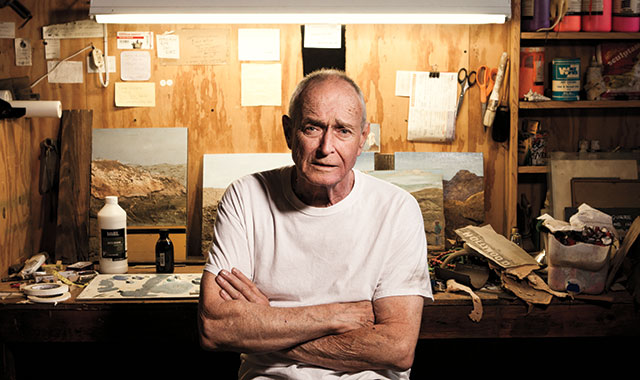

Llyn Foulkes / Photo by Kevin Scanlon

Scott Indrisek: Was it a daunting task, looking over this much of your work?

Llyn Foulkes: Oh, terrible -- like intensive therapy without a therapist. I had to go all the way back to my childhood. You start thinking about the bad things you've done and what an idiot you were then. It's my life, you know. And good or bad, you take it the way it is. Early on in the '60s I was pretty well known, and then I gave up what I was doing and tried to go back to what I was doing before. Art changed, Minimalism and installation art and all that stuff came in, and there wasn't that much in the art magazines about me in the '80s. I've had problems from the stock market of art -- let's put it that way. I've always been out of the mainstream because I always talk against what's going on in art.

SI: Did you have a peer group of artists on the West Coast?

LF: I've always been pretty much a loner, in the sense that I didn't really associate with that many other artists. That didn't help me either. In '67, when I won the Paris Biennale, I started to feel like I was losing my soul because I would go in the studio and the magic was gone. You just start copying yourself. And then I turned around and started going back into dimension in my paintings, because my paintings had been all flat during the '60s, except for the very early stuff, which was pretty raw. I put everything from dead possums in them to big black crosses painted with tar. But I didn't start getting into the art magazines until I started to paint flat.

SI: Have you always supported yourself with just your work, or also doing other things?

LF: In the early '60s I was driving a taxi and working in a hand-painted picture factory to make money. Hack paintings, they used to call them. You did what you did to survive. And then UCLA asked me to teach in '65. I was a really good teacher. But that drained me in my art, because I was giving it all out to the students.

SI: And all this time you've also been playing music. Is that a distinct endeavor from your visual art?

LF: I've always played music, as long as I've been an artist. When I'm doing music I don't think about the painting, even though some of the subject matter is the same. If I have songs about Disney, Mickey Mouse, or the Lone Ranger, any of that stuff -- it's in my paintings and my music both. But I'm also really into jazz and a lot of improvisation. See, when I was 10 or 11, I wanted to be a cartoonist. And then I heard Spike Jones. He had a novelty band; they made music that was kind of like cartoon music. So I identified with that, and I started imitating his records. And my mother would take me around up in Yakima, Washington, to the Moose Lodges or the Masonic Temples, and I'd do my little performance. She would've been like a stage mother if I'd been in Hollywood. I grew up in a family that was mostly women, because my father left when I was like a year old. The family never hugged or kissed or anything like that, but when I per-formed they would just go gaga over me and compare me to movie stars. So I started thinking the only way to be loved was to be famous. And when I was 17 or 18, I discovered Salvador Dalí, and then everything changed. I started to paint. My first painting looked a lot like Dalí; it'll be in the show.

SI: Why does Mickey Mouse appear so often in your work?

LF: My former father-in-law, Ward Kimball, was one of the "nine old men" at Disney Studios. He gave me a Mickey Mouse Club pamphlet from 1934; the first page talks about how they implant things in children's minds, almost unconsciously. This is the beginning of marketing. They go all the way down to little babies. People would rather go to Disney World than any of the other great scenic places in America. In Los Angeles, half the artists have worked for Disney. Not that they wanted to.

SI: When was the last time you went to Disneyland?

LF: Oh, I haven't been for years. The first time I went was '60 or '61. I had a beard then, and I looked like a beatnik. I was with my wife and child, and they wouldn't let me in. They had these big Aryan guys with blond hair and blue eyes, and one of them said to me, "If my kid looked like you, I'd whip him." I was fortunate because my father-in-law had a gold pass, and I finally got in.

SI: Can you describe some of the materials you incorporate into the dimensional paintings?

LF: I've always believed in what I call material difference. Most oil paintings, they may try to be dimensional, but they aren't -- because everything is painted with oil, everything is the same material. You start using different materials, and they have ways they lie in the picture plane because they reflect light differently. That's why, rather than trying to paint a sweater, I'll use a real sweater. Or I'll use real hair.

SI: What I remember from seeing your work at Documenta was the controlled environment for those pieces, including the way they were lit.

LF: I'm working with real shadows. So if you took the light and put it nine feet back, the painting wouldn't look the same. I'm making it look like the light is coming from within the painting rather than from outside the painting.

SI: You worked on The Lost Frontier from 1997 until 2005. Is that the longest you've spent on one painting?

LF: The Awakening (1994-2012) took longer, oddly enough, though it's the smaller picture. It started out being 9 feet and looked entirely different. The painting had to do with my divorce. And when I got the divorce I stopped working on it. It's gone through all these changes. But all the paintings have. The Lost Frontier went through a lot of changes, too; there was a different figure in the left side rather than the Indian. I hacked it out with a machete. Everything I put in a painting is made to last. So when I change my mind, it wouldn't be like Rembrandt painting over something, and you'd X-ray the painting and see what was under there and how he changed it. Oh, no, I had to chop it out. I had to drill it out. It was quite an ordeal over the years.

SI: What's the base that you're building on?

LF: I start with lauan wood. My main purpose is to try to get the painting to look as deep as it possibly can. When I look at a lot of big paintings, I think, yeah, they're big, but they're empty. And I just refuse to do it that way. If I'm going to do a painting that big anymore, I'm going to put as much as I can in there. People like Frank Stella talk about the space they make -- he's not making space. I look at those paintings that come out from the wall. They're pretty fucking ugly. And all they do is jump out at you. And he writes this whole book on space. Man, I say you're just taking up space. I don't want to take up space. I want to make it go back in the other direction. There's so much stuff popping out. I've got the same problem with installation art. It takes up all this room, people can put any junk they want in there, and you're supposed to walk around and make the association.

SI: So rather than taking up every available inch of space, you're putting the room inside the frame.

LF: Exactly.

SI: It has to be a challenge to display some of these works outside a controlled environment. Could it be in a collector's house, in a totally different context?

LF: Well, actually, The Awakening will be, because Brad Pitt bought it. I was surprised. But the other ones, the bigger ones -- I would expect them to be in a museum. In fact, for a painting like The Lost Frontier, I wouldn't want that to be in somebody's house. With all the work I put in on that, with all the spacing like that, why would I want just one person to enjoy it?

SI: You've always done most of the work on your own, with no assistants.

LF: Well, my eyes so are bad now it's really hard to do dimensional things, small things. I don't even know what's going to happen there. But I see other people who use assistants all the time, and I find most of their work boring. To me the process is extremely important; it's where you discover things. I could cite people like John Baldessari. You know there's no process involved, they have other people doing things for them. If you're not discovering things by the mistakes you make... And that's why I find so much art boring now.

SI: The retrospective travels to the New Museum later this year.

LF: Yeah, it's going to the New Museum in New York in June and then on to Kleve Germany in December. My last survey show never made it to New York so this is kind of a big deal. At first I was disappointed that the Whitney, Guggenheim and MOMA didn't take the show, but having learned more about the New Museum and their programming, I feel like it's the perfect place for me. I'm the bad boy in Los Angeles, and I'm sure I'm the bad boy in New York, and the New Museum gets that about me.

-Author, Scott Indrisek BLOUIN ARTINFO

More of Today's News from BLOUIN ARTINFO:

Like what you see? Sign up for BLOUIN ARTINFO's daily newsletter to get the latest on the market, emerging artists, auctions, galleries, museums, and more.