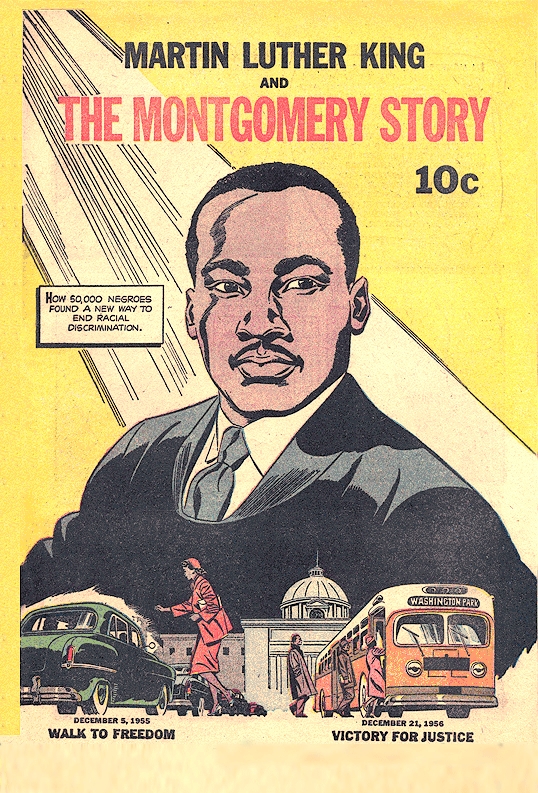

In 1958 Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. was the real-life superhero of a comic book that inspired disenfranchised American youth to take action against segregation. Today, the comic is finding a new audience in the Middle East.

When the Montgomery Bus Boycott ended in 1956 after resulting in a crippling financial deficit for the capital of Alabama's public transit system, a grassroots peace organization known as the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR) began exploring methods to solidify the growing momentum for civil rights in the South. With the aim of disseminating information about nonviolent protest to the semi-literate, the group decided upon the quick-to-grasp comic book format.

After securing a $5,000 grant, they consulted with Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. on a story line which would portray his early Christian upbringing and detail his peaceful resistance strategies, along with principles of nonviolence introduced by Gandhi to achieve India's freedom from the British. Dan Barry, who had signed the Tarzan and Flash Gordon strips, was commissioned for the illustrations.

The resulting "Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story" has been cited by some historians for motivating four black students to sit at the "whites only" counter of the Woolworth's in Greensboro, NC and order coffee. Unserved, yet undeterred, the "Greensboro Four" returned day after day, inspiring similar sit-ins. The resulting media storm led Woolworth's and others to serve blacks and whites alike. In 1964, The Civil Rights Act mandated desegregation in facilities serving the public.

With only a handful of the original 250,000 comic books still remaining, it would have been easy for the comic to fade into the annals of civil rights history. But an initiative by the non-sectarian American Islamic Congress's (AIC) HAMSA: Hands Across the Mideast Support Alliance has breathed new life into the piece.

Dalia Ziada, a blogger and human rights activist, first learned about the comic when she attended as a 24-year-old an AIC lecture in Cairo on nonviolent resistance. That night, she discovered that an uncle was about to have female circumcision performed on her younger cousin. Inspired by King and the methodology explained in the comic, Ziada successfully persuaded him to abandon his plan. She is now a crusader against the practice, of which she herself is a survivor.

Today, two-thirds of Egypt's population is under the age of 30. And Martin Luther King was only 26 years old when he became involved with the Montgomery Bus Boycott. This juxtaposition was not lost on Ziada, who now represents AIC's Egypt office.

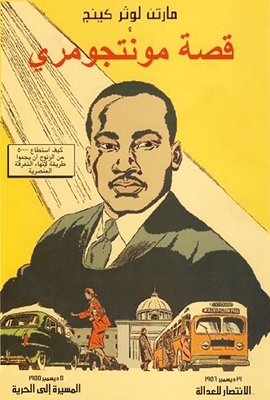

"We must learn that being young does not mean being weak and apathetic," says Ziada. "That is why I thought it would help to introduce 'Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story' in Arabic."

While translating the simple English of the comic was not a difficult task for Ziada, publishing the piece was. To sway the relevant officer at State Security, which had banned the printing of the comic, she invited him for a cup of coffee. Together they reviewed the pages line by line until all of his concerns were addressed.

"Then he asked if he could have some of the published books for his children when it came out," she adds.

The Arabic comic book has now been distributed in print and on-line to a network of young activists and bloggers throughout the Middle East, including Algeria, Bahrain, Iraq, Kuwait, Lebanon, Morocco, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia and Yemen. Feedback has been enthusiastic. At a book fair in the Egyptian industrial city of Mahalla, one woman grabbed the comic book with passion and scanned the cover, asking, "Is this Gamal Abdel Nasser?"

A Farsi version of the comic was rushed into production in June of 2009 as post-election protests were erupting. Translators in Iran helped put it together in a week, and the comic was soon being distributed digitally. The Montgomery Bus Boycott had resonance in Iran with the 2005 Tehran bus protests, which made headlines when one trade unionist, Mansour Osanloo, had his tongue cut by members of the Islamic Republic for seeking improved working conditions for his fellow bus drivers.

As with the violence in Iran, "Martin Luther King and the Montgomery Story" cautioned that brutality often accompanies steps towards peace. Scenes of a Ku Klux Klan parade, a cross burning, and the bombings of Negro churches and homes were vividly depicted within its pages. An impassioned King is seen imploring an angry crowd:

"Please be peaceful. We believe in law and order. We are not advocating violence. I want you to love our enemies, for what we are doing is right, what we are doing is just - and God is with us."

Now, with over 2,500 copies of the comic book in print in the Middle East, HAMSA* program director Jesse Sage says, "We don't expect the comic book will change the world. But hopefully it will ignite a little spark, and cumulatively a bigger process for peace will unfold."

* HAMSA recently announced the 2011 Dream Deferred essay contest, asking young people to read the comic and think about how they can apply nonviolent action as a means of addressing a civil rights challenge in their communities.