Nowhere in the New Testament does Jesus or Paul say he is rejecting Judaism and starting a new religion. In fact, the term "Christian" doesn't appear at all in the Gospels (Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John), which chronicle Jesus' spiritual mission; and only later, three times in the rest of the New Testament. The first utterance of the word "Christian" occurred when Paul was preaching in Antioch more than a decade after the crucifixion.

But the word "Jew" appears 202 times in the New Testament, with 82 of those mentions in the Gospels.

The evidence in the New Testament persuasively suggests that both Jesus and Paul viewed their teachings as Jewish revisionism---not a rejection of Judaism or the proposal for a new religion. If this is true, as it seems to be according to the Gospels and Acts of the Apostles (book 5 of the New Testament), then we must ask: Who launched Christianity? While the question presumes that someone had to fill that role, the answer may be that no one officially founded Christianity.

It just happened.

"It just happened" doesn't mean it mysteriously materialized out of nowhere. A firm foundation was needed to enable it to "just happen." While Jesus and Paul established the foundation for the new religion, neither of them officially initiated Christianity as a religion separate from Judaism. On the contrary, both remained dedicated to Judaism throughout their lives, as documented in the New Testament.

So why are so many people convinced that Jesus or Paul created a new religion?

Many who believe that Jesus had in mind a new religion cite his pronouncement in Matthew 16:18: "You are Peter, and on this rock I will build my Church." They jumped to the conclusion that "Church" in this statement means a Christian or Catholic Church, as we know it today--a building housing a new religion. But that doesn't make much sense.

The term "church" was derived from the Greek and merely meant assembly; some scholars say it was an error in translation and had nothing to do with a place of worship. Moreover, at the time of Jesus, there was no concept of a new religion. If Jesus had proposed a new religion he would have had few if any followers. Remember, all of his followers were Jews--and first-century Jews were fanatically dedicated to Judaism. Whichever way you cut it, Jesus' church was more likely the new synagogue, which would represent spiritual Judaism---a spiritual core that Jesus charged was corrupted by the Sanhedrin, the ruling body of Judaism.

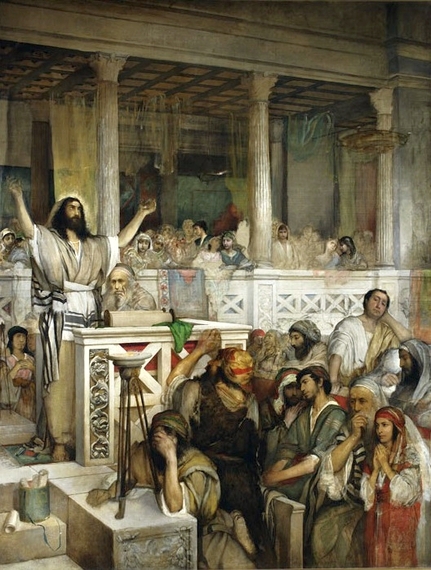

If Jesus conceived of a new church, why did he spend his life religiously celebrating the major Jewish holidays in the Temple in Jerusalem? And we must remember that throughout the years Jesus prayed, preached, and read from the Torah in a synagogue on the Sabbath:

"And he came to Nazareth, where he had been brought up : and, as his custom was, he went into the synagogue on the Sabbath day, and stood up for to read" (Luke 4:16).

Christian theologian Jean Guitton, in his book Great Heresies and Church Councils, states explicitly:

"Jesus did not mean to found a new religion. In his historical humanity, Jesus was a devout Israelite, practicing the law to the full, from circumcision to Pesach, paying the half-shekel for the Temple. Jerusalem, the capital of his nation, was the city he loved: Jesus wept over it. Jesus had spiritually realized the germinal aspiration of his people, which was to raise the God of Israel..."

Further evidence that Jesus did not envision a new religion was that he didn't claim one at his trial. Had he said he was no longer a Jew and had launched a new religion the Sanhedrin wouldn't have had jurisdiction over him. The Romans had given the Sanhedrin the authority to rule only over Jews. Even if the Sanhedrin had rejected Jesus' denial of being Jewish, it would have set off a ferocious legal debate among the Jewish rabbis and scholars--a type of debate for which Jews were famous. But that didn't happen.

Still, there are "experts" who insist that Jesus rejected Judaism and launched a new religion. But if that were true, how do they explain why Jesus' disciples didn't follow along? Why, after the crucifixion, did the disciples continue to worship at the Temple in Jerusalem--not in a new church edifice? ReligiousTolerance.org points out that:

"Jesus' disciples and other followers who fled to the Galilee after Jesus' execution appear to have regrouped in Jerusalem under the leadership of James, one of Jesus' brothers. The group viewed themselves as a reform movement within Judaism. They organized a synagogue, worshiped and brought animals for ritual sacrifice at the Jerusalem Temple. They observed the Jewish holy days, practiced circumcision of their male children, strictly followed Kosher dietary laws, and practiced the teachings of Jesus as they interpreted them to be."

There is ample evidence that Jesus didn't found the new religion. But what about Paul? Thirty years after the crucifixion of Jesus, when Paul made his third visit to the disciples at the Temple in Jerusalem, he still appealed to James, the brother of Jesus, and the other disciples, to drop orthodox Jewish practices to allow Gentiles into the new Judaism. But Paul made no declaration of a new religion. Consider also, had the disciples even hinted that they were launching a new religion they wouldn't have been allowed anywhere near the Temple.

The issue of declaring a new religion comes up again for Paul, when doing so would have saved his life. That he didn't declare a new religion at that time poses a formidable challenge to those who say "if Jesus didn't officially launch Christianity then Paul certainly did." But did he?

On that third visit to Jerusalem Paul was arrested after creating a disturbance at the Jerusalem Temple, where he incited a group of Asian Jews who attacked him for blasphemy (Acts 21:27-31). When he was brought before the Roman Governor, it was determined that the matter of blasphemy was strictly a Jewish affair and therefore should be adjudicated before the Sanhedrin. Fearful of his fate if he were judged by the Sanhedrin, Paul invoked his status as a Roman citizen and demanded that his case be heard before the emperor in Rome. His demand was granted (Acts 25:10-12), verifying the power and respect for Roman citizenship.

But if Paul believed that he had departed from Judaism and had launched the new religion of Christianity why didn't he say so, with his life at stake? Why didn't he say "I'm a Christian, not a Jew. I believe in Jesus Christ, who the Sanhedrin has rejected. As a Christian they have no Jurisdiction over me. You must release me."

And surely, given his status as a Roman citizen, he would have been released. But he didn't use that obvious defense. Only one explanation can account for Paul's puzzling behavior: he believed he was a Jew proposing a valid revision that embraced Jesus as fulfilling the Jewish Messiah prophesy. In a sense he may have even felt more Jewish than the Sanhedrin in embracing the Messiah Jesus.

So, instead of freedom, Paul squanders five years at the peak of his ministry, which included imprisonment in Caesarea, a lengthy treacherous journey to Rome, and then house arrest in Rome

Punctuating Paul's persistent dedication to Judaism and his Jewish identity, when arriving in Rome he summons the Jewish leadership. (Acts28:17-20). He bitterly complains to them that the Romans have no argument with him but that the Sanhedrin has charged him with blasphemy, when he has committed none--still believing that his form of Judaism was the right one. He was clinging to his Jewish identity. Note too that there is no mention in the New Testament narrative of any consideration of the argument (that would have given Paul his freedom) "I'm not a Jew any longer, I'm a Christian." Paul goes to his death as a Jew.

At that point in the development of Jewish Christianity, the converts were predominantly Gentiles. With Paul gone and Gentile conversions accelerating, many different sects sprang up. Irenaeus, an early Church leader, counted twenty forms of Christianity. And these Gentile/pagan dominant sects became increasingly distant from Judaism, taking on an independent Christian identity. Paul Flesher, University of Wyoming Professor of Religious Studies names numerous sects that the fledgling Christianity generated: Donatists, Gnostics, Arians, Adoptionists, Modalists, Manicheans, Montanists, Marcionites, Ebionites, Nestorians, Meletians, among others. These disparate sects, says Flesher, had disagreements about fundamental theological doctrines, choice of scriptures, and religious practices.

By the fourth century competing sects still flourished. That's why the Emperor Constantine initiated the Council of Nicaea in 325 CE, to sanction a unified Christian Church.

This broad-stroke sweeping history sketch documents how Christianity "just happened." But the newly established unified Catholic Church was still uncomfortable that its authenticity was tied to Jewish lineage and Jewish messianic prophecy. Thus, the church sought to sever the Christian/Jewish connection by stepping up vilification of Jews and Judaism. In this campaign the most devastating blow was the charge of "Christ Killers," with its lethal consequences for Jews. The fatal distancing of Christians and Jews that followed has only recently begun the process of reconciliation and healing, strengthened by Pope Francis' bold statement: "Inside every Christian is a Jew."

In 2016, in a rare occurrence, the first night of Hanukkah and Christmas Eve fall on the same date, December 24th. Since 1900 that convergence has happened only three times (1902, 1940, and 1978). 2016 is the fourth time.

Perhaps this rare event signals a prophetic time for Christians and Jews to celebrate the common foundation of the two faiths.

Bernard Starr, PhD, is Professor Emeritus at the City University of New York (Brooklyn College). He is organizer of the art exhibit "Putting Judaism Back in the Picture: Toward Healing the Christian/Jewish Divide."