Forty years ago, Brock Brower was a member of the New Journalists, the vaguely codified generation of writers who started sculpting their articles with the arcs and devices of literature. Unlike his white-suit or Hawaiian shirt-wearing brethren, Brower never became famous outside the industry despite having written a critically acclaimed satire of his trade and its relationship to celebrity in a novel titled The Late Great Creature.

Forty years ago, Brock Brower was a member of the New Journalists, the vaguely codified generation of writers who started sculpting their articles with the arcs and devices of literature. Unlike his white-suit or Hawaiian shirt-wearing brethren, Brower never became famous outside the industry despite having written a critically acclaimed satire of his trade and its relationship to celebrity in a novel titled The Late Great Creature.

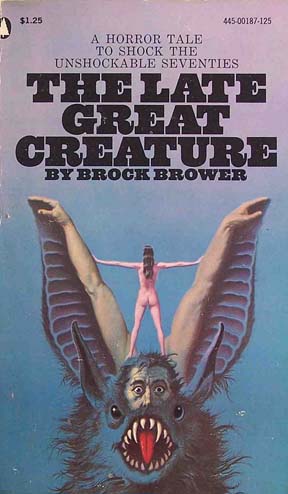

After a nomination for a National Book Award in 1973, Brower's angry, articulate, and downright clever novel receded into the underworld of forgotten paperbacks with dated covers. Now, after years of being out of print, The Late Great Creature has been reissued and Brower's hardboiled, horror-themed wit might finally find a new audience. It's at the very least found me.

The novel begins with Warner Williams, an alliteratively named stringer for Esquire debating with editor Harold Hayes about the reporter's article on a B-movie adaptation of "The Raven." The film's star, Simon Moro, is in the midst of a public breakdown after a bizarre appearance on a very Tonight Show-like show. The article may or may not run. Williams argues with his editor, "'Harold,' I try, 'Moro used to be part of all our bad dreams. The good part. Maybe even the best part. Why else this craze? He's only trying to stay in there as a going figment of the public imagination. These days it's terribly hard to be a horror.'"

Background: Brower himself covered Roger Corman's production of The Raven in the Esquire article "The Vulgarization of American Demonology" but in the novel, Brower used his source material for something far more complex than a simple roman à clef.

Now 80, Brower recently told me in an email interview about his motivations for mixing fiction and the reality of his career. "At the height of the 'New Journalism,'" he wrote, "I was determined to convert fiction back into the most up-to-date realism possible, including putting living public beings into the narrative."

When I asked Brower if any of his living public beings minded their starring roles in The Late Great Creature he replied, "The one hard case was Harold Hayes, my much loved editor at Esquire, whom I'd left behind to go to Life. And he balked some, but reluctantly signed a release. Guess what, later that decade I ended up writing his copy on 20/20 at ABC, when he and Robert Hughes lasted only opening night as co-hosts."

Fact: Brower wrote the show's signoff "We're in touch, so you be in touch."

As for the Hollywood characters in his novel Brower said, "Much gamier were the fictive characterizations I gave certain folk I'd met on the set of The Raven, such as 'Quincy Adams' or even 'Terry Cowan' as the director/provocateur. I made them admixtures of brute fact and imagined innards, and these guises 'said more' than any bio revealed about their real selves. I mined Peter Lorre the most."

Like Peter Lorre, Brower's fictional Simon Moro is a drug addict former star of German expressionist cinema and a onetime Brecht player. Moro is typecast as a villain, a "Gila Man," and vampire in a Hollywood of reproduced Ionian columns. "Instant archaeology," Brower wrote of Hollywood. "The glory that was never Greece, the grandeur that was RKO."

On the set of Raven (the definite article having been dropped for more "horror impact") Williams captures in this description of a shooting day the neurotic urges that drive horror: "He lunges into the coffin, rips at her grave clothes, his digits like scythes, lofts her out of there with one long boob flying, naked as a goat's udder. But high enough: angled just right, so that the boob whips past camera, the same dead-green lighting, with the nipple just over the other side of the rise, so to speak. You know it's there, but can't actually see it. Just like in King Kong, so Terry still has his family picture."

New Journalism tricks like abbreviations and fact checking notes left in read, in retrospect, like neo-noir immediacy. It's not for nothing that James Ellroy has given the reissue of The Late Great Creature a solid blurb as both authors operate on the assumption that behind those onscreen and daily fantasies of ours lie ontologically deep corruptions.

The acrimony between reporter and subject is inflamed by Moro's public transgressions, disrupting Williams' preconceptions for his article and, more importantly, his deadline. He confesses: "Damn him. I wrote him up as the Greatest Thing since Gangrene. I made him a monsterpiece. Damn his X-ray eyes. I bugled him and boosted him and succored him and damn near sainted him. Simon Moro could have been America's last King of the Creeps, the Man the Martians Come to See, but he crawled into town, spread his shaggy hands."

For the reader, Brower's writing is all loquacious zingers but the book's observations on culture are as hard-bitten as they are elegant. In our talk Brower rightfully claimed prophecy credit when I ask about our current obsession with celebrity flame out: "I had set out in the late 60s to write a novel about what I foresaw as the seizing future threat shaping up: our Celebrity Culture. And I chose deliberately to cast that culture into the throes of the most egregious pop art form that America offered: horror films with their stellar cast of scarifying monsters."

How does an American book this interesting become a literary ghost? I was born in 1975, a hair younger than the book, and in all my reading life of being obsessed with the same brew the novel is steeped in--celebrity, the 1960s, unreliable narration--I had never heard of it until its reissue.

Brower stopped publishing fiction and after 20/20, taught and did policy work. The Late Great Creature's extravagant digressions and structure also might have come one season too early. Like Brower's novel, Thomas Pynchon's Gravity's Rainbow was a hallucinatory ransacking of 20th-century pulp culture and it arrived only a year later, winning the National Book Award.

Another truth is that horror cinema was becoming less repressed and leaving the drive-in for adulthood, which may have dampened some of the novel's satirical bite about the disconnect between what we watch and what we really fear. Only nine months after Brower's novel was released, The Exorcist would inaugurate the post-Vietnam war horror film cycle and put our culture's anxiety regarding sex and changing gender roles directly on screen, without the need for mythical creatures.

And one of the novel's oddest monsters would also become quite real soon enough. At the beginning of The Late Great Creature Williams mourns the spiking of an article about Richard Nixon, for which the reporter had found an excellent thru-line in the then-candidate's victory gesture: "Both Nixon arms shoot upward, and then the big Nixon hands hang limp from the Nixon wrists, index and middle fingers forming two loose, pudgy V's. Like waggling claws, and has nobody but Williams ever noticed that a lobster goes through exactly the same motions when you pick one up by its back and drop it into the pot?"

Who needs a Gila Man if you have a Lobster Nixon?

The timing may have been off but The Late Great Creature remains a warped mirror lovingly polished with dark lyricism. Brower's novel may now have a chance to become part of all our bad dreams. The good part.