Originality and crackerjack dancing were on ample display at the Hong Kong Arts Festival's Contemporary Dance Series last week. Young Hong Kong choreographers furnished two double bills and a third programme crammed with seven 10-minute pieces. Sponsored by the Hong Kong Jockey Club, the series is in its fourth year and provides an important platform for emerging dance-makers.

In dance, 10 minutes is an awfully long time, and 30 minutes can feel like an eternity. While every piece opened strongly and imaginatively, a few failed to sustain interest.

The series was characterized by a preoccupation with male-male partnering, in four duets and one trio. The most exhilarating of these was Victor Fung's From the Top, which mocked the genre of male pas de deux - although that wasn't evident for the first few minutes, in which Fung led us down the garden path by creating a climate of fear onstage. The sight of a rigid figure, a burlap sack over his head, being manipulated by another man, immediately conjured up harrowing thoughts of recent ISIS executions deliberately staged for the benefit of millions of YouTube watchers.

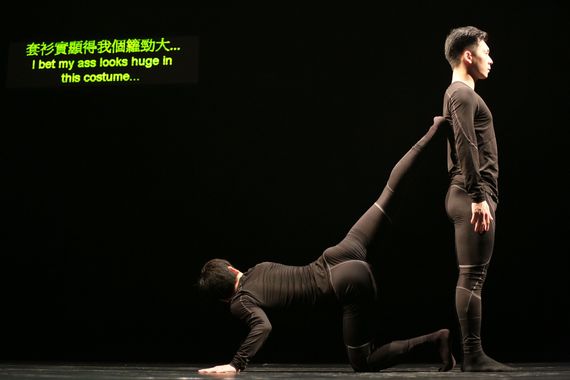

Suddenly, we hear a voice ("OK, thank you") and the dancers pause. We realize that we have been witnessing a rehearsal, and that this is a break for notes from the choreographer. As the voice rambles on, two electronic screens mounted against the backdrop light up periodically to spell out the dancers' thoughts (in both Cantonese and English). The dancers themselves remain silent, their faces expressionless.

"So exactly how am I supposed to be kidnapped more abstractly?" muses one.

"Seriously, I have no idea what you're talking about," fumes the other.

"Now you want to cut my solo, WTF?"

"I bet my ass looks huge in this costume."

It's even funnier if you don't understand Cantonese. You're in a fog while the choreographer is speaking - until the signboard lights up with the dancer's reaction.

From the Top incarnates the ever-present tension between dancemaker and dancers. A choreographer must contend with human bodies and their maddening variations, imperfections and unpredictability. A dancer, on the other hand, lives with the insecurity that he cannot deliver what the choreographer envisions. Communication breakdown is inevitable.

Our hapless dancers - Kenny Leung and Ronny Wong, both very talented and very funny - resume rehearsal, but frustration only grows as the choreographer makes increasingly ridiculous demands of them ("So I have to keep traveling, but stay in a split?") Partnered lifts get increasingly more convoluted. The movement veers from the genuinely moving to the clichéd - including those awkward upside-down lifts in which one dancer's face is two centimetres from the other dancer's crotch. The screens continue to register the dancers' silent scorn at the choreographer's pretentiousness ("So now I'm supposed to be transforming into Spiderman?")

From the Top and Justyne Li Sze-yeung and Wong Tan-ki's The Trouble-maker's Concerto (reviewed earlier for Bachtrack) were the two standout long pieces.

In the program of shorter work, thrillingly billed as a "dance-off," Pardon by Tracy Wong, Frangipani by Ivy Tsui, and Here is it by Li De kept Ballet to the People on the edge of her seat.

Pardon opens at the end of a lovers' quarrel. We watch Wong and her partner Mao Wei negotiate a truce, to a moody, minimalist score by Rafael Anton Irisarri. Wong and Wei don't dance to the music as much as they dance in and out of its shadows. The partnering is momentum-driven, rarely achieving a point of stillness or balance. The partners frequently connect by grabbing and twisting each other's shirts and hair - not the usual trite clinches that litter contemporary dance, but strangely tender and destructive impulses.

Wong is a powerhouse onstage - one of those rare performers who gives the illusion of no formal training, her dancing a series of organic caprices. Wei is a sensitive and elegant partner, slightly more subdued. At the close, Wong wraps herself around him from the back, in a tight, codependent grip, her hair hanging over her face, her legs around his waist. Together they form an ungainly creature, swaying gently as they stare out at us with slightly menacing affect. We are disturbed and moved at the same time.

Frangipani is a solo with a single idea, no story and no characters, and an unusually narrow range of movement set to an insistent, repetitive score. The simple lighting scheme outlines the petals of a frangipani on the stage, with the dancer at the center like a flower's pistil. For nearly the entire 10 minutes, the dancer's back is turned to us, and she doesn't move her feet except to widen her stance. A swaying movement emanates from her core and gradually seeps into her arms, her shoulders and head, and finally her legs.

The dance is one with its hypnotic score by Moon Ate the Dark (Welsh pianist Anna Rose Carter and Canadian producer Christopher Bailey). We hear the wind pick up. The petals fade, and the dancer is free to move, whipped around in a tornado. Tsui's performance in her own choreography is a tour de force, ranking with the most arresting solos I have ever seen, in both concept and execution.

For Here is it, choreographer Li De's choice of Junior Kimbrough's raw, pounding, dirty blues anthem, 'I gotta try you girl,' strikes a note of irony as three lean, elegantly sleek young men saunter onstage, projecting the metrosexual vibe of a 21st century Cary Grant. With their glossy, slicked-back hair and their smooth, jazz-inflected moves, they appear faintly predatory, their seductions aimed at the audience rather than at each other.

The blues fade away, and we hear a voiceover conversation in Cantonese in which the young men are discussing youth and freedom. The dancers cease posing for us, and face off against each other. There is less jazz in their movement now, more aggressive and staccato movement. They drag each other back and forth across the stage in anger or frustration. The blues return, but our young men are preoccupied, with battles to fight and tragedies to endure.

Tragedy, too, seemed to haunt Chloe Wong's Diffusion of the Silence. Her striking visual concept featured dozens of votive candles scattered around the stage, buoyed by a marvelously textured, evocative electronic score by Moon Yip. At first, the dancers are confined to tiny squares outlined by the candles. Later, they maneuver the candles around the floor, slowly and elaborately. In one mesmerizing sequence, the dancers crawl and slither out of the wings reaching desperately for a candle, but it is always just out of reach. The piece may be about addiction. The dancers' unwavering fixation on a candle became wearying, however. The audience needed a reason to care about these candles, but we never got it.

In 19841012, Rebecca Wong Pik-kei danced with her mother, Chan Mei-chun, in a touching but rather too literal reenactment of her birth. Particularly gripping were the opening sequence of contractions, and the middle sequence in which Wong was shrouded and dragged along the floor in a piece of stretchy white jersey (reminiscent of the ensorcelling things Martha Graham used to do with stretchy fabric). But most of 19841012 was too close to pantomime and did not reflect the transformational power of dance.

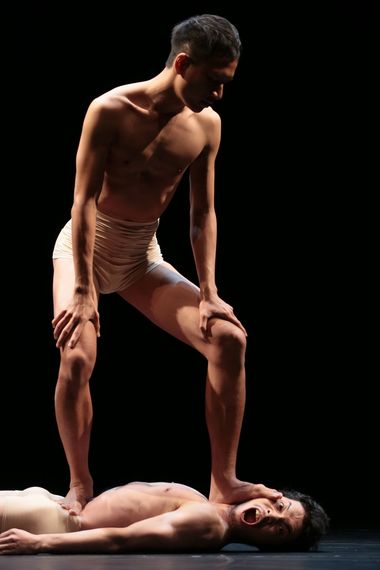

Ata Wong's Chater Road put one near-naked dancer on the floor while the other stepped on to him - one foot on his stomach, the other on his chest. They spent the next 10 minutes in a fascinating evolution as Bruce Liu changed his foothold on different parts of Takao Komaru's body, while Komaru slowly and painstakingly rose from the floor. Liu's primary task was to maintain his balance while executing a mysterious sign language. During which, Komaru had to sustain his oxygen intake with the weight of an adult man crushing his ribs, then his back, his skull, his wrist, his elbow, his hip, his shoulder.

Influenced partly by the Occupy protests that closed down an important thoroughfare in Hong Kong's business district last summer, Chater Road was performed in silence but would have resonated with greater nuance against a score. Lack of soundtrack does not automatically sink a piece, but it does put an extra burden on the dance to create atmosphere and convey emotion.

Hugh Cho's Remain with the Question was similarly handicapped. Cho crafted an artful sequence of bravura acrobatic movements for himself and Steve Ng to tell a tale of male solidarity. A soundscape of sorts was created by the pounding on the floor as they landed flips and cartwheels and body-slams, but the impact would have been amplified with music.

Cycle by Allen Yuan opened in silence, but midway through unleashed 'Rainbow' - a moody shoegaze ballad by Japanese experimental rock band Boris, featuring the wailing sounds of psych guitarist Michio Kurihara and Wata's sultry vocals. In contrast to 19841012, there was too much mystery in the movement that melded a repetitive series of gestures and contemporary dance interaction between its two male performers. A hint of narrative about a father and son, and about the father's daily travails as a shopkeeper, suggests itself. Ultimately, it feels like a very personal tribute - as did 19841012 - into which the audience is not fully drawn.

Aside from the two pieces performed in silence, the entire series revealed impeccable music choices and crafting of scores. Sophisticated lighting design also enhanced the entire programme, and even the less successful pieces revealed a remarkable sense of theatre.

Three of the 12 choreographers presented this season have been on this stage before. May the Hong Kong Jockey Club provide even more opportunity for these young talents, not just to display their finished work, but to develop their ideas in workshops and residencies without the pressure of a full-blown performance. Freewheeling Hong Kong, with its jumble of cultures, capitalism coursing through its arteries, its mistrust of Beijing, and roiling social tensions, is where the creative heart of China beats loudest (whether the mainland wants to hear that or not), and it is from here that the next generation of innovative Asian dance-makers and dance companies is most likely to spring, if given the time and money.