Over twenty years ago, Sally Mann published Immediate Family (Aperture), a book of photographs of her children playing on their family farm in Virginia, which was called "disturbing" by the New York Times and "degenerate" by the Wall Street Journal. The children were often nude, as the secluded farm was miles away from strangers, and the children's poses, innocent to her eyes, deeply disturbed many who saw them.

She said she and her children, collaborators, were trying to tell a story of growing up. "We tell it all without fear and without shame." Later she said, "The fact is that these are not my children; they are figures on silvery paper slivered out of time. . . . These are not my children with ice in their veins, these are not my children at all; these are children in a photograph."

At times she sounded defensive, at times uncertain why there was controversy at all. She had not prepared a standard response because she did not expect many people to see these photographs, much less for the pictures to become a cultural lighting rod.

Mann had been publishing small books with limited print runs, of interest to photography collectors and specialists, and imagined this body of work would reach a similar audience. But it was published in the midst of culture wars over government funding of "pornographic art" by artists like Robert Mapplethorpe, who also photographed nudes. It was a moment of intense interest in the propriety of art; transgression was seen as an existential threat to the moral fabric of American society. Compounding this problem, and inviting an additional slew of criticism and outrage, was the fact that she was a mother.

Several photographs showed her children in apparent danger. Critics felt a good mother would have removed them from peril rather than pausing to photograph them. This was seen as evidence of Mann's lack of maternal instincts. It is a testament to the strength of her work that the reality of the photographs went unquestioned. It was somehow forgotten that this was art.

As Immediate Family was reissued this year to coincide with the publication of Mann's memoir, we now have the gift of a greater context for the genesis of these photographs, what they meant to her, and the effect they had on her family.

"How I love those, children. And how I fear for them. And how real those fears can become, in just an instant. Right before my eyes," she writes. The photographs were her talisman against harm. When she feared great danger to her children, and that danger was averted, she would recreate her fear for the camera as if this could somehow prevent it from coming true. She describes this process as feeling "like some urgent bodily demand."

Through a window, she watched her five year old daughter Jessie play with a doll on a tire swing. Then Jessie disappeared. She asked neighbors to help scour the woods, calling out her name. She feared her daughter had drowned. "I stuck to the creek edge," she writes, "certain I'd see a flash of gingham, of white sock and patent leather Mary Janes in the water."

Her son's school secretary called to say Jessie had only walked down the road to visit her brother. The next day, Mann put a dress on her son and posed him as a drowned girl, face down in a pond on their farm, titling the photograph The Day Jessie Got Lost. "I prayed it would protect us from any such sight, ever," she writes.

When her son Emmett was hit by a car, she ran into the road and held him as he bled from the head. Onlookers assumed he was dead. After he recovered, she tried to photograph him in a way that would capture the feeling of that moment. She chronicles her attempts: a photograph of his bloody sheets in the hospital; his head blurred, as if he might be screaming or shaking off a nightmare; a self-portrait of her face next to the crumpled, blood-stained sheets. None of this worked.

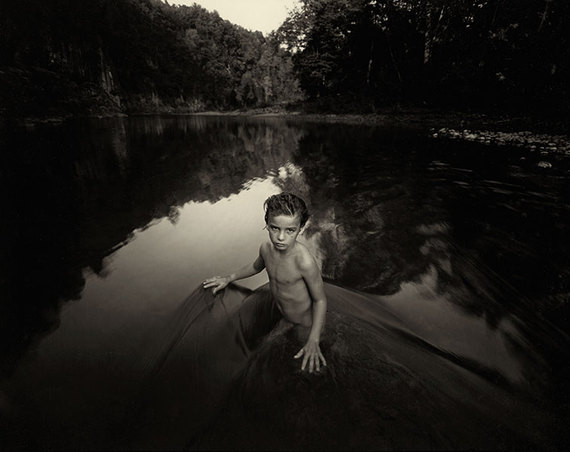

Finally she came upon the right subject: Emmett, nude, alone in a river on their farm. It took a week to make the final photograph, after nearly a hundred iterations: Emmett submerged in water, Emmett holding onto a black rubber inner tube, descending into the river wearing water goggles, standing beneath a broken tree, and at last the final photograph, Emmett touching the water's surface with his hands, as if to hold it in place, as the river uncontrollably flows past him, inexorably moving away, on toward a bend in the river, and out of sight. "I had tried to exorcise the trauma of the experience by following my own command," she writes, "to 'photograph what is important, what is closest to you, photograph the great events of your life.'"

After an article in The New York Times Magazine brought her work to a wider audience, she started receiving disturbing letters, some from victims of child abuse, others from prison inmates. She was especially hurt by letters calling her a bad mother, suggesting the photographs had emotionally damaged her children, and put them at risk of attracting "pedophiles, molesters and serial killers."

She recalled Oscar Wilde's response to personal attacks, that "the hypocritical, prudish, and philistine English public, when unable to find the art in a work of art, instead look for the man in it." But she found different rules applied to a mother.

Until the publication of her memoir, she had not publicly discussed the fact that a man in a nearby state became obsessed with her children, writing their schools to ask for yearbooks, calling the local hospital to request birth certificates. He subscribed to the town paper to read about their ballet recitals and school prizes. When she asked a policeman for advice, he told her to buy a shotgun.

Mann carried a photograph of this man in her wallet for years, fearing he would appear at one of her lectures. She obsessively locked windows, made sure her children were never alone, and asked police for more protection. "We live routinely now with a hitherto unendurable amount of stress," she wrote a friend, "Each time it ratchets upwards, we adapt to it." She remained silent, knowing her critics would feel vindicated.

"This year, though," she wrote in another letter, "the good pictures of the kids might not come. The fear may scare them off. My conviction and belief in the work was so unshakably strong for so many years, and my passion for making it was so undeniable. Now, it is no longer the same: I am frightened of the pictures."

Questions about the reality of the work, different moral rules for mothers, and voluntary suspension of disbelief, all so vigorously debated in the pages of various journals, could no longer remain academic to Sally Mann. "How can a sentient person of the modern age mistake photography for reality?" she wrote. And yet legions of them did.

But what endangered her children was also a great testament of her love. "She has a hard time letting us know how much she loves us," said her daughter Jessie, years later. "But I've also realized that each one of those photographs was her way of capturing, if not in a hug or a kiss or a comment, how much she cared about us."

Sally Mann told her students to photograph the great story of their lives. The great story of her life was her adoration of her children, which was entangled with her fear for them. Her photographs of imagined harm were self-portraits of her grave, solemn, vast love. In trying to ward off danger, she inadvertently endangered them, while simultaneously, paradoxically, recording her unbounded devotion. "Unwittingly, ignorantly," she writes, "I made pictures I thought I could control."