Sometimes we all need to be reminded of the bigger picture. In a cultural climate rife with paranoia, strained by war and increasingly concerned with its own decline--the newly opened American and Islamic wings at the Met Museum are the perfect opportunity to see anew.

There's something inherently optimistic about a great museum--the episodes of history peaceably contained on canvas, the craftsmanship of rivaling countries displayed in neighboring galleries--but in these wings especially we find a renewed sensitivity for perspective. The museum does an exceptional job of organizing the exhibits within freshly refined geographical and historical contexts.

The Islamic wing in particular--officially known as the Galleries for the Art of the Arab Lands, Turkey, Iran, Central Asia, and Later South Asia--has gone to considerable length to display the collection according to geography. By doing so it distinguishes a broad range of cultural influences in its holdings for the first time. It differentiates between a stunning variety of themes and motifs, and most importantly it defines Islamic artwork largely in its secular incarnations.

Distinct, though those cultures may be, the newly initiated will be impressed by similarities such as the widespread love of embellishment and adornment. In everything from the smallest corner of an illuminated manuscript to the most expansive architectural elements, one finds an attention to detail at once intimate and monumental.

The Simonetti carpet dating from early 16th century Egypt, is one of the most dazzling examples of this juxtaposed scale. At nearly thirty feet long you have to stand back to see it all at once, but its intricacy insists that you move in closer. Once there the color dissembles into a dancing contrast of reds and green. You begin by tracing a simple line, but soon find yourself on a course through its entire geometry. It is highly abstract, and yet precisely reminiscent of the natural world--the indecipherable tangle of a forest, the luminous veins of a flower petal.

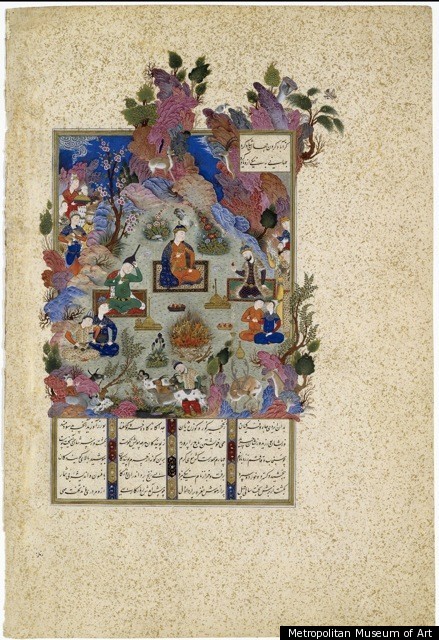

Over and over again, the detail in miniature paintings from India and Iran inspire a sense of other-worldliness. On close inspection, the tiny Feast of Sada from Iran, which is nine inches square, doesn't seem like a small painting, so much as a big painting made to fit in one's hands. The deeper we are drawn to the hair-line patterns on the men's clothing, the individuality of the flowers, the animals hiding in the landscape, the less it feels like we are looking at a small world, but like we've been given a glimpse into a world we don't see normally.

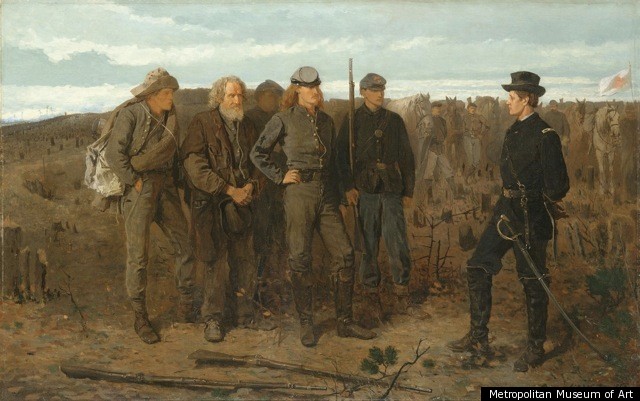

If the task of the Islamic wing has been to differentiate the varieties of a long tradition, the American wing is organized according to the narrative of a culture trying to define itself. Visitors will appreciate the shift from art that first looks highly European, both in theme and execution, to a perspective that becomes recognizably American. Whether it's the harvest of gourds in still-lifes by Raphaelle Peale, or portraits of bedraggled soldiers in the Civil War by Winslow Homer, or the unfiltered immediacy of landscapes by John Frederick Kensett--we see art that is rapidly being shaped by a new frontier.

In both wings the natural world plays a central role. In the Islamic wing we find nature in its stylized essence--more often we recognize its abstracted experience rather than a reproduction. In the American wing nature is the medium of human desire, but we also find the beginnings of a more modern perspective in its observation.

Thomas Cole's View from Mount Holyoke, gives us the drama of the American experience--in the foreground, an impenetrable density of virgin forest as the darkness of a thunderstorm recedes above, while in the valley below the land is bright, cultivated, still--the pattern of fields like a reassuring quilt. The contrast is clearly defined in terms of man's relationship to nature--an admiration of its beauty as well as a desire to harness its power for himself. A vista not just to behold, but to conquer.

The landscapes of John Frederick Kensett are another breed entirely--small, simply composed and quickly executed, they are light incarnate and stunning in their modernity. The paintings belong to a group called the "Last Summer's Work," completed in 1872, shortly before he died. We don't find anything troubled, however, in the painter's hand. If anything, the directness of the observation in Eaton's Neck, Long Island nears abstraction--a blue-grey sky is resting on the green-grey water, while a dark curving arm of land reaches out between them. It seems almost static except for three tiny ripples as the water touches shore, and has a delicacy and a directness that suddenly seems removed from any time or school of thought.

The Met's new wings give us room to remember what we know, and a chance to recognize it in different interpretations. They remind us of the shared desire of all eras and cultures to depict the world around us, the worlds above ours, the worlds that govern our own.