Grand civic gestures, courtesy entrepreneurial public-private partnerships, and some deep-pocketed donors are pumping new life into some old guard cities, among them New York and Philadelphia, where urban parks are "in" and planners speak of the "Highline effect" as they once did of the "Bilbao effect."

So, what's happening in Boston, home of the Emerald Necklace, a system of parks and parkways designed by a succession of Olmsteds and almost certainly the world's first urban greenway? The situation in Boston is akin to the absurdist Waiting for Godot or the amusing Waiting for Guffman... in Beantown it might be called Waiting for Parkman.

The Muddy River, Back Bay Fens, The Emerald Necklace. Photograph courtesy of The Cultural Landscape Foundation.

Parkman is not some mythic rich savior with an appropriately punning name; it's a reference to George Francis Parkman, Jr. (1823-1908), whose eponymous fund created more than a century ago with a gift of $5 million still provides a modicum of support for Boston Common and other parks and open spaces. Problem is, the waiting game in Godot and Guffman proved to be a folly, as the omniscient oracle never arrived. Will the same thing happen in Boston? Is there no 21st century Parkman?

Commonwealth Avenue Mall, The Emerald Necklace. Photograph courtesy of The Cultural Landscape Foundation.

First, some background: the five-mile Emerald Necklace park system that stretches from Boston Common to Franklin Park was designed between 1878 and 1895 by Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., with Charles Eliot and John Charles Olmsted, and further involvement by Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. and the Olmsted firm into the 1920s.

The elder Olmsted, famous for his designs of Central and Prospect Parks in New York City and the U.S. Capitol Grounds in Washington, D.C., along with masterworks in Buffalo, N.Y., Louisville, K.Y. and elsewhere, considered the Emerald Necklace the most important work of his career.

Leverett Pond, Olmsted Park, The Emerald Necklace. Photograph courtesy of The Cultural Landscape Foundation.

There are two things to note here: Decision-making about the Necklace is complicated because it straddles two municipalities -- Boston and Brookline -- and incremental capital improvements have been made. A plan begun in the mid-1980s (adopted in 1989), and enabled by the publicly supported Olmsted Historic Landscape Preservation Program, resulted in a $32 million program overseen by the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Management, with support from then-Governor Michael Dukakis. The Necklace's five parks -- Jamaica Pond,Olmsted Park, The Riverway, the Back Bay Fens and Franklin Park -- each received $1 million to advance essential work, not to mention preservation master plans to guide their future.

Now, a $92 million effort is underway to restore to health the civil engineering structure, flood handling capacity, historic design intent and ecological vitality of the Muddy River, which runs through the Back Bay Fens section of the Necklace. As more people come to the parks, creating a greater maintenance burden, will the area's individual, institutional and corporate philanthropists step in to protect this enormous public commitment? Will their giving extend to the parks?

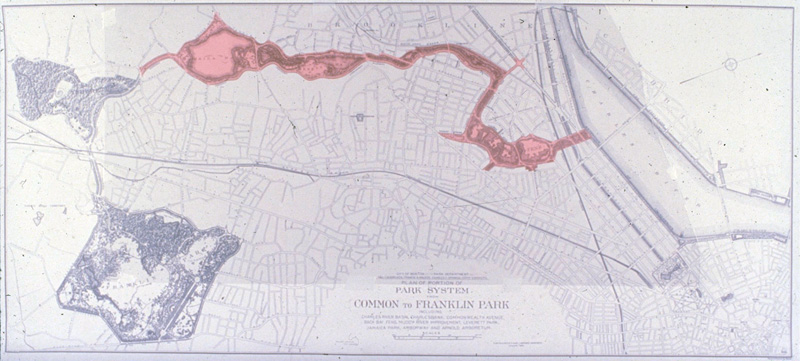

Map of the Emerald Necklace. Highlighted portion shows section subject to $92 million project to stem critical infrastructure collapse. Photograph courtesy of The Cultural Landscape Foundation.

Critical infrastructure collapse -- flooding of the Muddy River, The Emerald Necklace (1996). Photograph courtesy of Hugh Mattison.

At this point it might be easy to conclude the parks are victims of Yankee thrift. Malcolm Rogers, director of Boston's Museum of Fine Arts, confronted this issue a few years back amidst a half billion dollar capital campaign. Rogers was told there were finite giving opportunities in Boston. His response? "Can I tell you who the people are who say all these campaigns are a problem -- the people who say, 'If I give to you, who will give to the hospitals?' They are the people who don't give at all." Rogers says: "There is plenty of money to go around."

Boston Museum of Fine Arts entrance onto the Back Bay Fens, The Emerald Necklace. Photograph courtesy The Cultural Landscape Foundation.

Henry Lee, former president of the Friends of the Public Garden a non-profit citizen advocacy group formed in 1970 to work with the city to preserve/enhance the Boston Public Garden, Common, and Commonwealth Avenue Mall, says: "Museums are smart -- if you are fundraising you can give a room or almost anything with a big enormous plaque -- it is hard to do that with parks. In Boston, you can give trees or benches, but the city will not allow advertising."

Lee is referring to the fund raising successes of two Emerald Necklace neighbors, the Museum of Fine Arts and the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum. In Boston Magazine's online article -- "A Big Pile of New Museums!" -- George Thrush, director of Northeastern University's School of Architecture, recently wrote the newly opened "Renzo Piano addition to the Gardner is the third step in what will ultimately be four dramatic changes to the Boston museum scene. When the re-building of the Harvard Art Museums in Cambridge is complete sometime next year, the area will have seen almost a billion dollars invested in the art curatorship of The Institute for Contemporary Art, The Museum of Fine Arts, The Gardner, and the Harvard Art Museums -- in less than a decade."

That's right... "almost a billions dollars" for four museums. Clearly Bostonians recognize the value of great art institutions, but what about the parks? Lee, reflecting on his four decades of advocacy and fund raising, says, "The private sector has to make substantial contributions."

Benjamin Taylor, the former publisher of the Boston Globe (1997-99) and current Chairman of the Board of the Emerald Necklace Conservancy, expressed his concern:

There are a lot of great causes in the city and region -- but parks are essential to our quality of life... Not a day goes by that I do not appreciate my two minute walk to Olmsted Park -- I bike, walk, look at birds, take visitors there -- it is the fabric of my life -- one of the reasons I live in this city.

Public Garden, The Emerald Necklace. Photograph courtesy of The Cultural Landscape Foundation.

Betsy Shure Gross, the former executive director of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts Office of Public Private Partnerships (in the Executive Office of Environmental Affairs), pondering the problem, cites lack of governmental leadership. "Look at all of the other major public private partnerships for parks, in other cities the partnership between the private and public leadership has been extraordinary," she says, concluding, "We do not have the municipal leadership to create such partnerships."

Why not?

Bostonians, as we've seen, are rightfully proud of their major art institutions, so why doesn't that translate to the masterwork of one of their greatest artists? Where are the public-private partnerships? Where are the Boston equivalents of major philanthropists like Barry Diller and Diane von Furstenberg who donated $35 million to New York's High Line? When it comes to philanthropy for Boston's parks, is there a grass ceiling?