Being a public academic has its ups and downs. My recent appearance on the BBC Newsnight program discussing the UK publication of the Prince Harry naked photographs in Las Vegas generated an unusual amount of polarized feedback, some of it positive, some of it, er, shall we say mixed?

Why not just say what you really think? As a postgraduate journalism lecturer I teach and encourage student debate on the definition of the public interest in privacy law and yes the clips used in my Newsnight interview were selectively edited from a much broader conversation but it wasn't an unfair characterization overall of what I wanted to communicate. My most recent research focus is on emergent relationships of the 'public interest' and the 'interest of the public' as I'm sure there will be a lot more discussion on these issues as the frequency of reality checks for inadequate national regulatory and legal frameworks trying to handle global digital media publication ramps up. Soon enough this issue will be back in the news with another absurd example of Britons getting their news from abroad.

Let's face it, most of us don't read printed newspapers anymore, or printed magazines, or printed books for that matter. It's not a good or bad thing. We just don't do it. Nearly three times as many people visit the Daily Mail website (the UK's most popular national newspaper website) in a day as buy the newspaper in an entire month. Amazon announced in August that on its site customers are now buying more e-books than hardcovers and paperbacks combined. We are in the midst of an era of the digitization and globalization of media. I think everyone basically gets that.

What is less clear is we fully understand the cascading impact of these digital changes on our media regulatory, legal and ethical frameworks like the official press guidelines by the Press Complaints Commission (PCC) on what publications in their jurisdiction can and cannot print. Some of these are simply no longer 'fit for purpose' and no amount of indignant regurgitation of small print legal scare tactics is going to change that. The sound and fury over the Sun newspaper's publication of the Prince Harry naked Las Vegas hotel room photographs is a case in point.

U.S. entertainment website TMZ bought some photos for a reported £10,000 (what a deal!) and published the images on their website on August 21, 2012. They were able to do this without any threat of legal reprisal because they are not operating in the jurisdiction of the PCC's Editors' Code of Practice. Their TMZ website is however freely available on the public Internet in the UK. From this point on the story was living, breathing and living on the Internet and no amount of legalize or moralizing about what is in the 'public interest' of UK citizens was going to change that reality.

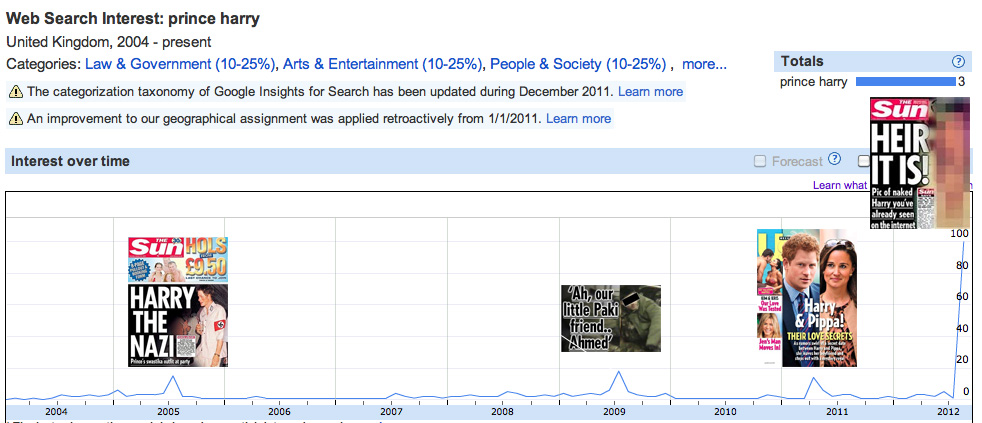

By noon on August 22, 'Prince Harry' was trending on Twitter in the UK alongside another big news story, the imminent release of GCSE exam results. Like it or not, UK citizens were deeply engaged with the story. Three of the top five Google search terms relating to Prince Harry included 'TMZ' as UK citizens searched for the news source where they could view the photographs. Interest in the story was overwhelmingly local with England and Ireland occupying more than 50% of global searches after which interest dropped off dramatically to Commonwealth countries and finally the rest of the world. The main TMZ story was filled with advertisements targeting British consumers as the near real time advertising networks recognized and fed the demand with targeted UK products and services. By the time the Sun published the pictures in print on August 23 over an estimated 13.5 million UK citizens had already seen the photographs online and the search popularity for the images was already starting to wane. The Sun subhead said as much, "... pictures you've already seen on the Internet." According to Google search statistics the naked images over these three days were more than five times as popular as any other Prince Harry related search theme since 2004 when they started keeping detailed stats. The previous most popular search peaks were when Prince Harry dressed up in a Nazi uniform in 2005, when he made a politically incorrect comment about "our little Paki friend" in 2009, and the Royal Wedding in 2011. All of these are stories familiar to any British news junky (and all provide insight in one form or another into his private life) but the naked images were more popular than all of them put together.

All of this data reflects a basic fact. Anyone interested in seeing the images, UK public interest laws be damned, just went online and searched for them or clicked on a link from one of their friends on a social network. The only feasible way of stopping this from happening would be to filter all of the content providers on the Internet in a similar fashion to the relatively successful censored public Internet in China. A strong case could even be made that by stifling the ability of UK publications with global audiences to publish the photos, the PCC was exercising anti-competitive practices and forcing UK news consumers to access their media from competitors abroad.

The actual result of the attempted PCC ban was the creation of a 'grey market' in news and information in the UK (not unlike the grey online markets that exist in China from users deploying proxies and software to get around the 'Great Firewall') where the images were available to any UK news consumer with a browser and Internet connection, just not through regulated UK media channels. These grey markets have flourished in recent memory in the UK from the Ryan Giggs affair to the identities of the two women who brought sex charges against Julian Assange in Sweden. Unless the regulatory frameworks are updated for reality, we can expect more examples of Britons getting their British news from abroad in a similar fashion to how the most popular online news sources in Zimbabwe, about Zimbabwean news, come from the UK due to an ongoing debate of what the Zimbabwean public thinks is in the public interest and what the Zimbabwean government thinks is in the public interest. Establishing privacy law in digital media at a national or regional domain is a slippery slope and as useful as putting in place restrictions on environmental emissions at a national or regional level. Pollution doesn't respect national borders so global regulators have long understood that the only really feasible way forward is to pursue global solutions, even if they are difficult and full of delicate negotiations. Data and information on the Internet doesn't respect national borders either and finding a way forward can be equally contentious as reflected by the differing national perspectives on the value of whistleblowing and the Wikileaks publication decisions. Nonetheless if there is any value in these digital media privacy and publication laws it will ultimately be found at the global and transnational levels.

The public interest and the interest of the public are merging in a gradual democratization of not just news creation and consumption but also the broader news agenda. Democratizing the news isn't just a concept, it is a shift in being for media in the UK. Popularity does not translate to public interest but engagement and community are new and powerful metrics in the news business and it isn't the exclusive domain of professional journalists to establish the news agenda. This democratization is happening at all levels from news gathering to publication. The person who took the photos of Prince Harry and sold them on is in the freelance photography marketplace and was richly rewarded for the snapshots. Ignoring the reality that 'everyone is a reporter' in the digital media era is attempting to put the genie back in the bottle. Think of the power and news value of the images coming from the tunnels of 7/7 or the streets of Syria.

Everyone may not operate according to long established principles of professional journalism but that doesn't change their ability to capture media with potential news value wherever and whenever they like. If Prince Harry's minders didn't want images splashed all over the world from the Las Vegas hotel room they needed to take all of the cameras away. And where does that stop? Again, like it or not, this is the era we live in. Like printed newspapers, the traditional definition and boundaries of reporting will never return so we're better off adapting than resisting. Following the Sun publication, over 12,000 army cadets and soldiers set-up a Facebook page posing naked as camaraderie and in a 'salute' to Prince Harry.

Monitoring, measuring, and responding to audience data in near real-time is one of the most powerful instruments at the disposal of a digital media organization. These tools are at the heart of the 'digital first' initiatives driving most of the newsrooms in the country. For example instead of the Sun editors or a bunch of elite pundits working off virtually no reliable data making guesses over why UK citizens were so interested in the Prince Harry naked photographs (representations of Britain abroad, revelations about his security provisions, etc) why not just ask them? The public were, after all, in the midst of viewing the images when the Sun was in the midst of debating publishing the images. How much stronger (or weaker) might a public interest defense have been from the Sun if they were able to represent data on why so many UK citizens were searching for and sharing the images while the PCC attempted to maintain its ban on UK publication. This type of polling and sentiment analysis in digital media can be done nearly instantly as demonstrated in so many political stories reflecting 'buzz' or sentiment about campaign issues. We might have been surprised by the results amidst the righteousness of attempting to define 'public interest' with the images already out there.

The Sun's decision to publish was an invitation for legal action. But despite all of the threats and indignation there was, naturally, no legal action taken against the newspaper for its apparent breach of privacy law and the PCC Code of Practice. So it was all bluster. What is the point of establishing such a clear code of practice if media organizations in clear breech are not penalized? It must have been obvious that it would have looked so naive to pursue the case with the images already splashed all over the Web. So why try and regulate it in the first place if media organizations can just flaunt the rules? My personal hope, though I am not optimistic, for one of the outcomes of the Leveson Inquiry is that it produces a starting point for progressive self regulation of these issues and recognizes the reality that until enforceable global regulation is a possibility, it is the publishers that will need to make these ethical decisions on public interest informed at least partially by the interest of the public when the content is readily available from abroad.

Leaving governments or public bodies to exclusively define privacy concerns is just as fraught with challenges as media self regulation. After all, who will watch the watchers? Privacy in digital media is a massive issue involving relatively poorly regulated and monitored lucrative electronic trails for businesses and sophisticated and still poorly understood surveillance of user activities by governments and law enforcement agencies around the world. The privacy of the reading material and the privacy of the reader are intertwined and inseparable. Essentially we need realistic, publicly and collaboratively developed, and globally aspiring digital media privacy and regulatory frameworks for a digital media era.