I've recently started to read comic books again, both new and anthologized titles, with the habit jumpstarted by DC Comics' 2011 re-launch of its line. I first started collecting when I was about 8, and it quickly became a past time that brought me great pleasure. I especially enjoyed team books like The Legion of Super-Heroes, The Uncanny X-Men and Avengers because of the slew of powers and personalities presented.

And I was drawn to the female heroes, often illustrated beautifully with interesting juxtapositions of power and identity. There was the tall, green-hued She-Hulk, for instance, who could throw around tanks with wit and verve, or the nuanced, highly actualized weather goddess Storm. Somewhere, I knew that I saw my ideal self in these women.

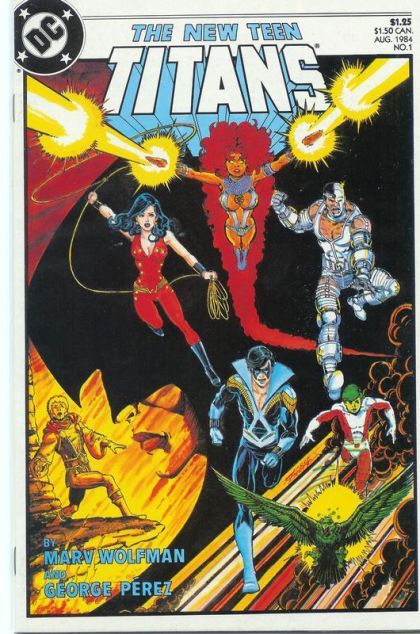

A title I paid close attention to, like many others, was The New Teen Titans, written by Marv Wolfman and drawn by George Pérez. The Titans were a group of young heroes with diverse origins, some of whom were the protégés of DC's most celebrated champions. The series became highly popular during its 1980s run and was noted for its humanistic elements and superb art. Wolfman gave dimensions to his characters that rang true of early adulthood experiences while Pérez had an eye for vivid detail when rendering architecture, costumes, flesh and physiques.

When I first came upon the series, I was intrigued to see that Robin was hanging out with a group of beings outside of Batman, and that he was being depicted in a way that felt darker, sexy, more serious. The other guys in the group--Changeling, Cyborg, Kid Flash and later Jericho--had great histories as well, but it was the women whom Wolfman consciously shaped to form a special trinity.

The New Teen Titans, a highly-popular comic series during the 1980s. The first few years of the series run can be found in The New Teen Titans Omnibus, Vols. 1 and 2.

One, Wonder Girl, aka Donna Troy, was the adopted younger sister of Wonder Woman; Troy was bestowed with prodigious strength, a lasso, Amazonian bracelets, the power to glide on air currents and levelheadedness beyond her years. (She once declared she felt like the Mary Tyler Moore of super heroines.)

Troy's roomie, Starfire, aka Princess Koriand'r, was alien royalty who absorbed solar energy and discharged said power in the form of flight and bolts of force. She came from a culture that valued emotion and sensuality over intellectual achievement, and hence freely loved those whom she called friends--including a certain Boy Wonder, her dude Robin.

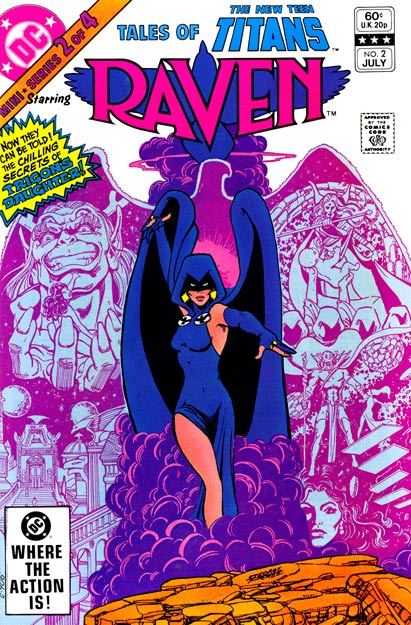

And then there was Raven, a character who has arguably one of the most interesting backstories in comic history. Raven hailed from the dimension of Azarath, a supernatural pacifist culture that was formed to oppose a powerful, murderous being named Trigon--who happened to be her father. Raven could teleport and was an empathic healer, able to sense emotions and remove other people's physical/emotional wounds by absorbing them into her body, with the trauma gradually dissipating.

She also had the ability to outwardly project her interior being in the form of energy. She called this manifestation her soul-self, which appeared as a huge shadow figure mirroring her own shape and garments. The soul-self could affect the physical world, yet its greatest power was what it could do to human beings once they were enveloped in its folds, forcing people to psychically go within, to look at who they were in all their nasty glory.

Raven was constantly facing herself as well, perennially in meditation during down time and seen as aloof compared to her peers. She had discovered that to become too angry, too passionate would unleash the power of her father--her own personal, very horrible inner demon.

I can't say that the metaphors to be found in Raven were consciously apparent to me as a young reader. I was more caught up in the suspense of the series, the rapture of gazing upon Pérez 's art and the voyeuristic experience of being with heroic yet addled characters. But after revisiting the series in anthologized form as an adult, Raven's wonder as a walking paradox becomes more apparent.

The comic character Raven, as created by Marv Wolfman and George Pérez.

Comics highlight intense drama, acrobatics, body blows and psychedelic displays of energy--yet here was a character who constantly challenged that world. Because Raven hailed from a pacifist society, the very nature of comic setups was anathema to her. Rather than another warrior character ready to bash heads, you had a woman who asked for friends and fiends alike to stop fighting, who vanished from sight when she was overwhelmed by battle.

In a violent medium, she brought to life the philosophy that resorting to fighting as a first or only solution is inherently perverse. It was unexpected ideology from a comic character, particularly one with evil heritage, whose pursuits are often about fulfilling the parameters of serialized fiction. A reoccurring, pacifistic mainstream hero was a pretty revolutionary stance, and Raven continues to hold that place of honor when considering how "attack" has become the de facto mode of existence in online conversation, political battles and broadcast fare.

Raven did eventually confront her father Trigon in a story arc that led to her transformation into a more centered being. As she changed, so has my own perspective as a comic reader. There's now less of a need for the pages to fulfill an ardent desire for adventure, though that fulfillment is still there, and there's more awareness of vibrant art and color, themes, pacing, weaker storytelling and gratuitous bloodletting. I've also found myself looking much more closely at the archetypes present in characters, including that of a darkly clad young woman who was frightened to feel yet experienced pain deeply, who looked at her demon in the eye and let him go, and who continuously called for peace.