Education never ends... It is a series of lessons, with the greatest for the last.

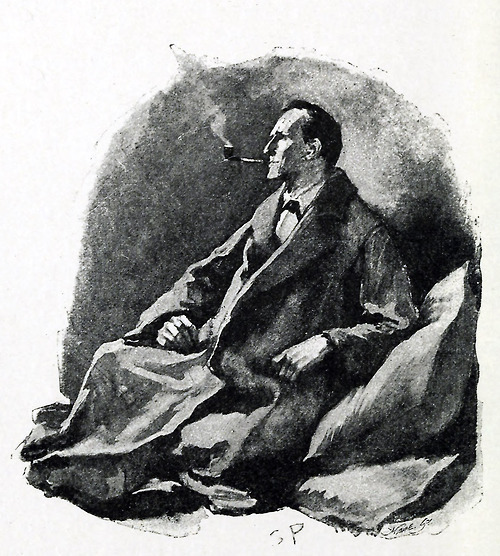

-- Sherlock Holmes (the original)

Reimagining famous fictional characters always brings out their richness of possibility, even when we don't like the reimagining. In this they are like the figures of mythology: capable of endless elaboration.

In the hands of Steven Moffat and Mark Gatiss, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's Sherlock Holmes has reappeared, but this time as a manipulative intellectual lacking in empathy or warm feelings. Ably played by Benedict Cumberbatch, this Sherlock surrounds himself with dangerous criminals, a former CIA contract killer, a landlady with a shadowy past, and an emotionally injured Dr. Watson (Martin Freeman) addicted to violence and intrigue.

The primary difference between this Holmes and the original is that whereas the Holmes of Victorian England pretended to be a heartless and disembodied intellect, the modern version really is.

The Holmes of Doyle was a man of strong if hidden passions and firm moral bearings. He understood the lights as well as the shadows of human nature. The Holmes of "Sherlock" boasts of being a "fully functioning sociopath" who exploits people he does not understand and for whom he does not care. His closest approach to real friendship turns up unexpectedly at Watson's wedding, after which Holmes slinks out of the reception, aware that he doesn't really belong with the celebrants.

What is the result of over-reliance on the lone genius style of intellectual domination? (Spoilers coming.) In the last episode of the series Holmes faces Charles Augustus Magnussen, an expert blackmailer who frustrates Holmes's final efforts to unmask him. In response, Holmes pulls a revolver and shoots him dead, thereby crossing the line into lethal criminality.

At a deeper level, the pulled trigger signals the downfall of the modernist attachment-free intellect. In its defeat it can fall back only on brute force. Intellect without passion or conscience has lost its bearings -- witness what it has inflicted, from atomic weapons and planet-heating industry to unregulated GMOs -- and fallen into an abyss from which not even warm-hearted Watson can rescue it.

"His whole life was in the intellect," observed a Manhattan Project scientist about its director, Robert J. Oppenheimer, a graduate of the New York School of Ethical Culture. Only after the test blast did the scientist begin to fear the fallout of his actions. Only after. The heart that might have warned him had been silenced too long, suppressed by intellectual vanity energized by destructive impulses left to ferment in the unconscious until the blast at Jornada del Muerto.

Not long ago I heard a climate scientist respond to a phoned-in question by stating that for humanity stuck on an overheating planet, the game was pretty much up. No reason for any more hope. That's the modernist materialist intellect for you: a possibility that does not show up to be measured or controlled simply does not exist. Bang.

When the image of arch criminal Moriarty reappears, Holmes is brought back from a death sentence as the lesser of two evils; but this Holmes has merged with his enemy to become the essence of one evil: mind displaced from its fleshly home and hubristically unaware of its own limitations. This Holmes fascinates us not as a complex and conflicted man, but as a soulless intellect that operates primarily as a symptom of our mechanized way of life.

"It's a wicked world," noted Doyle's Holmes, "and when a clever man turns his brain to crime it is the worst of all." What might he have said to his modern counterpart during a chance meeting in the busy streets of London? Would he have recognized his own shadow? I think he would, and that capacity for self-reflection is what separates him forever from his reimagined version. After all, it was the first detective of 221B Baker Street who spoke what might have been a warning for the century of scientifically amplified realpolitik to come:

Violence does, in truth, recoil upon the violent, and the schemer falls into the pit which he digs for another.