Star Wars has been touted as a modern myth since the 1988 Power of Myth conversations between journalist Bill Moyers and mythologist Joseph Campbell. "I think that George Lucas was using standard mythological figures," noted Campbell, who saw in Star Wars the Hero's Journey cycle of departure, initiation, and return he had written about in The Hero with a Thousand Faces. The interviews took place on Lucas's ranch in Marin, California.

More recently, freelance journalist Gerard A. Murphy asks: Has The Force Awakens, the latest Star Wars installment, "simply co-opted an already consumer-infested culture? Or does it contain a deeper mythological template that has something to say to the zeitgeist of the modern era?" He asks these questions after his seven-year-old son pleads for a Darth Vader watch for Christmas.

Murphy answers "Yes" to both questions. Mythic motifs in the Star Wars films include a reactionary striking back against the global push for equal rights, the striving hero, the advising wise one, and other dramatic figures that mirror our own desires and struggles in "a new movie but an ancient script."

Toward the end of his life Campbell mused on the possibility of a new myth for our time, nominating the image of Earthrise as a possible beacon of it. But in other interviews he acknowledged that no single myth could ever hold the unscripted diversity of all human experience, in our time or in any other.

My decades-long study and teaching of myth convince me that Star Wars and other epic crowd-drawing media projects--the "mythology" of Star Trek, the Avengers, and the entire Marvel universe, for starters--are not modern myths. Instead, we are confronted by what Ursula K. Leguin recognized in The Language of the Night as submyths: gripping, storied images, figures, and motifs as powerful as Superman, perhaps, but without devotional depth.

A submyth looks and acts like a myth and borrows stirring mythic themes and characters, but it lacks the transformative total involvement of authentic, living myth. However much it moves us, we leave its presence as spectators, knowing it to be fiction.

In other words, Star Wars and its fantastical troupe of Hollywood productions borrow the feel and excitement of myth without offering what a genuine, time-tested myth offers: "thousands of years as an inexhaustible source of intellectual speculation, religious joy, ethical inquiry and artistic renewal," as Le Guin puts it.

Myths when taken seriously and enacted as rituals and wisdom teachings serve as traditional and sacred stories for entire cultures. They form the core components of worldviews, they found religions, they illuminate spiritual paths, and they compensate psychologically for the deficiencies of their time of origin, bringing into public consciousness that which has been thrust aside. To those who experience them as true they offer the story-rich sense of participating actively in a sacred and meaningful cosmos.

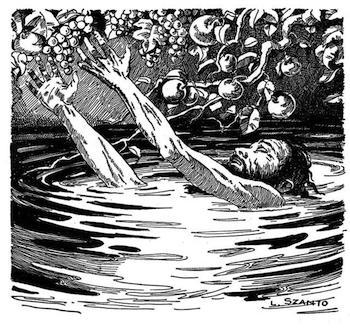

By tapping the human need for myth without being able to fulfill it, Disney, Pixar, Marvel, and their fellow media giants swallow enormous global revenues while dangling cinematic fruits like those hung before mythic Tantalus, a dethroned king doomed to sit hungering in Hades while grasping for what stays just out of reach. Tantalus serves as ongoing example of mistaking entertainment for spirituality, plastic for magic, fast food for real food, and submyth for myth: myth not as lie, archaic science, or ideology, and certainly not as commodity, but myth as localized sacred story deepened by generations of retelling.

By promoting and overemphasizing the violent Hero, the media giants of our day also deprive us of other examples, mythic or otherwise, of how to face conflict, corruption, and breakdown with wisdom and peaceful strength. Campbell's Hero is an ideal figure striving for self-perfection and cultural renewal; the well-worn and endlessly repeated hero of Hollywood casts a shadow that looks more like a bloodthirsty monster who massacres all his enemies or dies trying. (Perhaps the poet William Stafford was right: "It is time for all the heroes to go home / if they have any....")

At the same time, however, these dazzling submythic silver-screen productions bring hints of the power of myth and story to millions, some of whom refuse to stop at being tantalized. Many moviegoers and TV-watchers look further, into the ancient sources of tales rich in lessons and examples, hints and wisdoms commented on extensively by those who study mythology, including CG Jung, Hermann Hesse, Thomas Mann, Jean Houston, Christine Downing, Mircea Eliade, Marie Louise von Franz, Ginette Paris, and of course Campbell. To study myth reflectively is to acquire new modes of vision and hearing from tales found around the world.

Instead of settling for submyths, confusing them with real myths, we can open submyths like doors into more spacious theaters of possibility, where images connect to their cultural lineages, futuristic visions roam unconstrained by merchandise, and intuitive laws of the imagination hold sway.

"The real mystery is not destroyed by reason," remarks Le Guin. "The fake one is. You look at it and it vanishes. You look at the Blond Hero -- really look -- and he turns into a gerbil. But you look at Apollo, and he looks back at you."