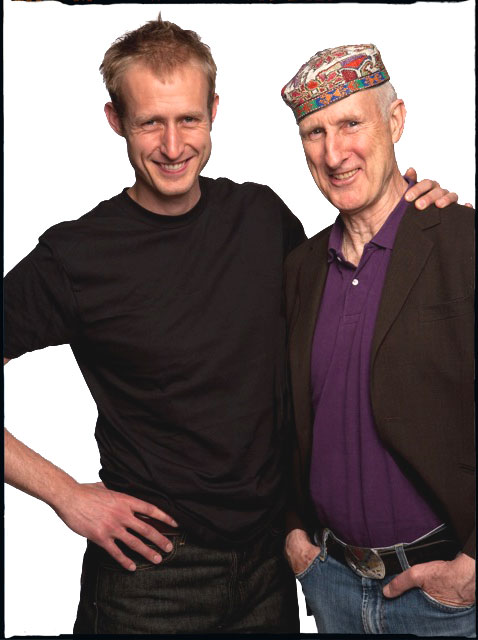

John Cromwell and James Cromwell. Portrait by Leslie Hassler.

How many children get tucked into bed at night and are told, "Now Johnny, Daddy is going to tell you the tale of how he smuggled the Black Panthers into his parents' house while they were away?" Most people think that their parents' stories are embarrassing. But most people's parents aren't Oscar nominated actor and political activist James Cromwell. Son John Cromwell and his co-director Joshua Bell realized the profound and historical relevance of James' story. Their depiction is by turns funny, truthful, and moving.

A .45 at 50th is a short documentary about James Cromwell's involvement with the Black Panther Party in the late 1960's. But what is little known is that he actually snuck the Black Panthers into his own parents' house while they were out of town! How many Safe Houses have a Doorman? The surprise of the film is that it is darkly funny.

John Cromwell came up with the wonderful tag line: J. Edgar Hoover Wanted to Kill My

House-guest. Once you have the set-up of the out of town parents, the comparison between why most children hope their parents will go out of town (beer and cigarettes) and why James Cromwell hoped his parents would go out of town (house one of the most notorious and feared Civil Rights groups in history) lends itself to a kind of hilarity.

Watching the film, you completely see what love and respect John has for his father's bravery and willingness to follow through on his beliefs. But what makes the film wonderfully unexpected is his underplaying the incredible danger of the situation. In a completely dead-pan tone.

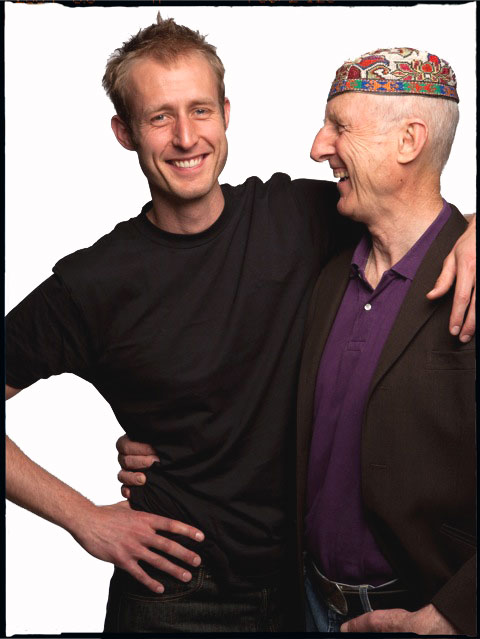

Spending time with both James and John together is a wonderful experience. Firstly, there is the incredible resemblance. Additionally, they both have profound intelligence and humor. And then, there is the height! John is 6'8 to James' already very tall 6'7. There is a certain amount of affectionate teasing between father and son that goes on, and it is so enjoyable to be around.

Jamie, how did you get introduced to the Black Panthers? In the film it's a beautiful blonde. Was this a cinematic embellishment?

James: (laughs) Amy Tobin was dark, and she was married to the only genius I ever worked with, Richard Foreman. (avant-guard theatre pioneer) They were separated and we were working together in Stratford and we started a little Guerrilla theatre which we conducted on the lawn before the performance. Richard Foremen did the piece and it was very provocative and all the unions struck to shut us down. We had fist-fights! It was incredible.

So you have a long history of confrontational and politically relevant theatre! How did this begin?

James: My father was blacklisted. I started in theatre. I was at Cleveland and I went to London for the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare's birth. Coming back, my father had found a tiny squib at the bottom of the theatrical page of the New York Times, that said they were a theatre company touring in the Deep South and that they were looking for directors and actors. So, I went down, auditioned and I got on a plane to New Orleans. Met the head of our theatre, went to our house, and there was a sign on the door that said, "Coloreds Only". And I thought, "Oh it's quaint, it's a throw-back to an earlier time."

Uh-oh....

Then we went to a restaurant, and John O'Neal (one of the founders) was black and we were actually thrown out of the restaurant. I had never been thrown out of a restaurant before! So, I got up to take a swing at the guy, and John said, "No no no, it's alright." And advised the restaurant owner that he was in violation of John's civil rights. Then we rehearsed the play and went to Mississippi in Macon, and the Black church had been fire bombed and then the little girls were killed in Alabama. Then I went to the freedom house in Macon and heard a 14 year old girl explaining to an entire room, I had never seen so many black men congregated together in one place, how she had been kicked and beaten and spit upon trying to integrate the lunch counter at Woolworth's in Macon. A young man whom I had played football with in Pelham New York, Mickey Schwerner, and Chaney and Goodman were missing, they were civil rights workers and they had been killed. Those were my first workings under the Student Non Violent Coordinating Committee. We toured Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia and Tennessee.

What was it like to be there during that period?

James: It was an intense time. The Freedom Summer (1964) and the bus (freedom) rides had been just before. We were doing Purlie Victorious by Ossie Davis and Waiting for Godot. These people had never seen movies, theatre, television, anything. They had no frame of reference. They thought Purlie Victorious was absurd. But then, to show them Waiting for Godot! Where you couldn't put three of the words together and make any reasonable sentence that matched anything that they knew! But Fanny-Lou Hamer, at an intermission in Indianola said "I want you to understand. We're not waiting for those two men. We're not waiting for anyone to show up and save us, we're taking our futures into our own hands." She was able to get, within the context of her own life, exactly what the play meant.

How was it, to perform for an audience who had never seen a play?

James: I often wondered how much the audience was getting, and I would sometimes speak to them after the show. Once I asked "Did you think Godot was coming?" and a woman in Greenville raised her hand. She was wearing a black glove, she could only afford the one pair. And she said, "No." She was so sure. And I said, "How did you know?" And she said, "I looked in the program and his name wasn't there." Now, I had never encountered an analysis of Beckett that went, "He's ain't coming, because nobody's playin' him!" It's the most sophisticated theory I've ever heard.

John Cromwell and James Cromwell. Portrait by Leslie Hassler.

John, was the story in the film one you had heard probably countless times from your Dad?

John: One of the ones. Not so much one that he would tell us, but maybe one I heard at dinner parties.....

The flashback scene where you play your father giving the Black Panthers a list of things they can and cannot do in the apartment is inspired. How did you make a potentially life-threatening situation so hilarious?

John: That was a very last-minute choice, that last scene. That was me almost directly teasing my Dad. It was an inside joke between myself and my siblings. (John has a sister and younger brother)

What it was it like to make a movie as father and son?

John: This was very easy, very painless. I simply had an interview with him. And it was just me, listening to my Dad telling his stories.

Jamie, in the actual story while the Panthers are hiding out at your house, you are sent on a bike from phone booth to phone booth to covey messages. Did you believe that if you followed the instructions, that the men in your house would stay safe?

James: That's all I knew. I was a little soldier. I had no idea what the larger picture was and I only had one job. To get from one phone booth to the other, and every hour call in to find out what information needed to be conveyed.

What did you feel when you found out that you had done your job correctly and still, the man you were housing, "Big Man" Howard, was arrested and charged (falsely) with being in possession of a weapon?

James: It happened differently than in the film and if we do a full-length version we'll show how it really happened. In real life, I went down to the arraignment because I didn't understand what the hell had happened. I had done my job. I knew my friend whose father was the lead violinist in the New York Symphony had had the gun. I had seen it. I knew he had passed it off. I got down there and William Kuntsler (famed civil rights lawyer) was defending Big Man. And the prosecutor got up and lied to the judge, and said that Big Man was arrested holding the weapon. And Kuntsler got up and screamed, "You LIE!" and I'm this little bourgeois kid from Westchester and I thought, "Do people really lie in court?" (laughs) So I got an education. The Panthers used to say, "All of us are in jail. Some of us are in maximum security, and some of us are in minimum security, but never forget, you are in jail." And then I realized: That's what they meant.

John, what is it like to play your own parent on film? Obviously there's a natural resemblance...

John: In this case, the mannerisms and those things are built into me anyway, so I just played it like any other part. It was just me being a person in a situation. I wasn't doing an impression of him.

James: Please, he does impressions of me at the drop of a hat!

Do you?

John: No, my sister does it much better.

(laughs) John, What did want people to get from this film?

John: We had interviewed him for three hours, so when it was all cut together the thing that struck me was his willingness to put himself physically in danger for this thing that he believed in. To be an activist in the sense of really participating; feet on the street. Doing this thing. As much as I think that the internet is a powerful tool, to me it's inspirational to hear about people who actually were there and did it.

Are you a writer first?

John: No, writing is a brutal, laborious under-taking, I'm a director first. But writing is the only way I'll get the stories made that I want to tell.

Did you watch your dad growing up? Did you always know that this was something you wanted for yourself?

John: Yes, I always wanted to be an actor. But I want to have more control than an actor has. I want to tell the story.

What are you working on now?

John: I'm developing this film into a full-length film. There are volumes of material about COINTELPRO and that era. It's totally relevant to what's happening now with our civil rights, NSA and wireless wiretapping so it's a major undertaking as far as writing. I'm very much a believer in technical accuracy and procedural accuracy. There's a lot a research to do, but I think it's going to be a very exciting film.

Do you think filmmaking is a form of activism, a way of getting a message to the people?

John: It certainly can be. It can be very powerful. Anything that's truthful. My ability to be honest and truthful in any cinematic sense is a kind of activism, even on the subtlest level. You also have films like The Cove, which are very inspiring. If we talk about films that changed the world, that one really did. It's really affecting things in Japan. (Ethical treatment of Dolphins)

Would you consider directing someone else's writing or script?

John: Ideally, I'd like a writing partner, and we can discuss ideas and then they can write them (laughs) and we can collaborate in that sense, but until then, if you want something done right you have to do it yourself.

Jamie, in the film, you talk about heroism really means.

James: What is magnificent about humans is when they decide to turn and stand. If they respond with non-violence on principle and hold their ground, they are really magnificent.

Where does your willingness to fight come from? Many people have beliefs, but prefer to negotiate from their armchair.

James: I had a resistance to authority. Until men learn to celebrate and operate on the feminine aspect of themselves and stop the oppression of women, children, the environment, other species, we don't have a world to live in. It's not a world that anyone chooses to live in. My heroes, Thoreau, Agee, have all articulated this since Shakespeare and even before, but I think Shakespeare said it the best. In King Lear, he actually pinpoints the dysfunction in his own culture and because he's such a great playwright he mirrors the dysfunction in any culture. I believe Lear's only flaw is his anger. That he has no control over it. There are only two emotions, love and fear. If men don't acknowledge their fear and suppress it, they put anger on top. They project their fear onto someone else and see an enemy and then act with anger and violence. I think Lear learns, by suffering, that if it happens to the least, it happens to me.

A .45 at 50th won Best Film at The 1968 Project. See it online: