Near Extinction

Around 70,000 years ago, Homo sapiens nearly went extinct. These were our ancestors, the progenitors of every human alive today: lithe, large-brained, exceedingly clever and inventive, and innately attuned to the voice of the land. A brutal ice age was slamming the northern hemisphere, decimating humans of varying species spread across vast Eurasia. Add to this an epic volcanic explosion on Sumatra, Indonesia which blew a suffocating blanket of ash for thousands of miles and dropped global temperatures by almost 30 degrees. Africa, where our stoical ancestors were living at this time, would have been relatively protected from this apocalyptic winter. Yet the land must have been dry and big game scarce, and these humans were squeezed through what is called a "bottleneck event," a winnowing of population down to a few thousand individuals, scattered in isolated pockets around the continent. All that we are--our particular brand of human empire--almost never was.

Expansion

By 50,000 years ago the ice age was retreating and temperatures rising. Those uber-hardy Homo sapiens who had survived began to migrate: east across the Arabian Penisula toward India, west into Mesopotamia and Europe, and north into the steppes toward Russia and the land bridge to Alaska. In 40 millienia--a blink on the eon scale--we had colonized every corner of the globe. That bottleneck event was like the contraction of matter before the Big Bang, a population explosion that has carried us beyond the orbit of 7 billion human beings. The UN projects that number to reach the staggering range of 8 to 11 billion by 2050.

Checks and Balances

The problem is that there's been nothing (since the Black Death in 1350) to check our exponential growth. Humans have made the ultimate biological leap, divorcing ourselves from the process of evolution which shaped our specific design and balances the network of life. Survival of the fittest no longer applies to us; we have circumvented, or outsmarted, that rule with the products of our advanced consciousness: technology, agriculture, medicine. Simply the concept of "population control" sounds eerily dystopic, an evil curtailing of our natural right to multiply. We apply this same healthy entitlement to the world's resources, cutting down and digging up and burning and eating whatever and however much we like. Earth is ours, and we are its master race: this has become our story, our collective myth.

Impact

For years we have been noticing the effects of our aggressive occupation of the planet. The comprehensive report released in March by The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change details the alarming changes familiar to us by now: rising temperatures and sea levels leading to dangerously erratic weather patterns which attack coastal cities and vulnerable islands and cause inland drought. Most of us acknowledge that the way we have been living, according to our myth of dominion, is unsustainable. We are already past the tipping point. Yet we allow ourselves the luxury of democracy and debate. We humor the opinions of grossly misinformed or corrupted politicians who deny global warming, and we suffer the influence of colossally powerful oil and gas corporations with tremendous stake in the status quo.

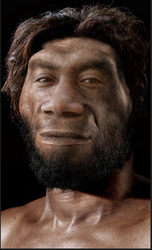

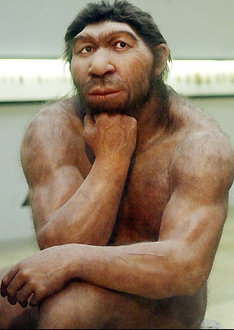

The Way of the Neanderthals

The Neanderthals also put great stock in the status quo. These humans had occupied Europe for 200,000 years before Homo sapiens arrived from Africa, hunting big dangerous game, crafting sophisticated stone technology, and living in communally supportive groups, kept small in number by the unforgiving fluctuations in climate. Ingenuity--a departure from the norm--is not afforded to small, stressed populations; instead they stick to what has worked. Neanderthal tools recovered by archeologists thus reveal little variation over thousands of years. The Neanderthals' technique of knapping and hafting stone was skillful, but rigid, ultimately unable to adapt to the changing world. They could not exploit the treeless steppe tundra, with its lack of ambush cover, which the ice age had created. By 27,000 years ago they were extinct. This was not their fault. They were victims of circumstance and bad luck; their incapacity to adapt and form a cohesive, evolving culture was a function of their limited and geographically separated population. We, however, have no excuse.

Bye-Bye

Humans too have become rigid, intractible in our reliance upon outmoded technologies (gasoline-powered cars, coal-burning power plants) which are poisoning our atmosphere. Our rigidity derives from our gigantic group size--big things have a hard time changing direction--but also from our complacency, our enslavement to convenience and comfort, our refusal to give up what we've gotten used to. Reconsideration requires stepping back, sometimes scaling down--and we have become addicted to dogged progress, to growth for its own sake. We often justify our culture by referring to the ideals of our "forefathers," by which we mean the political, enterprising men who wrote our Constitution. But our true ancestors were those stoic, flexible, intuitive creatures who understood the value of revision, of foresight, of listening to the Earth. We, their descendants, ignore the voice of warning, or if we hear it, we assume that futuristic technology will descend like a deus ex machina and save us (and the planet) in the end. Yet the powerful among us look only as far ahead as the next quarterly report and political term. The warnings will get louder, but soon it will be too late. We will no longer be able to buffer ourselves from nature, and the irrepressible force of extinction which has governed humans for millions of years will reassert itself.

For the planet this will undoubtedly be a good thing. For any survivors, an opportunity to evolve, to become again an animal in accord with the Earth. A new, wiser, more respectful kind of human who will look back upon our efforts as impressive but primitive and doomed, the way we look back upon Neanderthals.

Or, we can become that new kind of human now.