By now, there is no question that representational painting rooted in the classical idea of skill is again the heart of a living culture. It may not have access to all the apparatus of institutional and financial reward the broader art world has to offer, but it has caught fire and finally matches the standards of a culture. What was once a loose web of lonely artists, and then a tiny and isolated ghetto of friends and enthusiasts, has exploded into thousands upon thousands of practitioners, scholars, fans, amateurs, and collectors. This gigantic community is continuously in contact with itself over social media, convening here and there at packed conventions, and showing and teaching in its own constellation of galleries, museums, and schools.

Apart from these external signposts on the way to a culture, this revivified painting movement (which lacks an adequate name, though some advocate for "postcontemporary," a term I quite like) is also reckoning with the internal demands specific to its cultural content. Which is to say, the critique and advance of its art. This process has been terribly stunted in this movement, as critique and advance are often stunted among persecuted minorities. On the one hand, survival usurps luxuries like analysis in terms of resource allocation. And on the other hand, criticism feels like participation in the very persecution the minority continuously resists.

As the persecution of this painting movement fades, and its numbers grow, it has felt itself on a surer footing and matured to the point of asking: what do these skills serve? what is our art? Inevitably, the cohesion of a community defined by a technical ethos must splinter under pressure of the question of goals. But this is a healthy splintering. Asking "What is our art?" will unleash a thousand divergent personal visions. This is where we wanted to go.

At the broadest categorical level, there will be two answers to these questions. They involve two concepts of the relation of skill to the work.

The first concept, which is the default concept for this painting movement, is that all available skills should be brought to bear on the problem of making a picture. That is, all tools of depiction - anatomy, perspective, still life, landscape, lighting, color, rendering - they all go in, as subject matter permits. They are difficult skills to gain, we were once mocked for pursuing them, and they are profoundly expressive tools. Therefore the formulation and execution of the picture should use what they offer. The picture should be a heightened simulacrum of the real: the real made meaningful, the invisible truth revealed through the organization and adept depiction of life and matter.

This is a good concept, but it is not right for all artists. It is not even right for all the artists who think it is right for them.

The second concept goes back to the foundation of the modernist approach to technique, its often absurd claim that its artists were trained in high technique and could paint representational masterpieces anytime they wanted... but chose not to. It is wrong to make such defensive claims for your artists, because it obscures their real virtues. But there is nothing wrong with the formulation itself. And I believe this formulation is the other broadest-level answer to the question "What do these skills serve?" Some classically trained artists are going to set down some of the tools in their toolbox. They will be informed by their knowledge but not defined by it. They will not seek a transparent or elevated epistemology, but instead will work to express a personal epistemology, deformed as it is by obsessions, tics, and emotions. They will select a subset of the available tools to express their idiosyncratic visions.

I believe that the full maturation of this painting movement will be marked by the emergence and acceptance of artists drawn to this second solution to the problem. I've had occasion to formulate this set of ideas because I wanted to explain to you why I find Felicia Forte such an exciting artist. I like her work, yes, but I also think it is exciting.

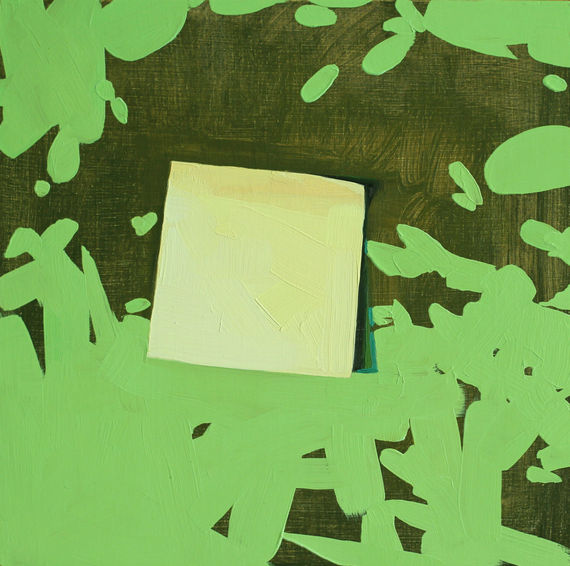

Look closely at this seemingly simple painting. It is a post-it note stuck on patterned wallpaper. It appears cartoonishly reductive. And yet two points in the image betray very sophisticated techniques: there is the keen observation of color shifts at the soft edge of the post-it's shadow, and there is the subtle, continuous variation of yellows across the curved surface of the post-it as its angle relative to its light source varies. These passages assert, in a sense, the authority of the rest: the background that is indeed as simple as it looks, the square-within-a-square composition, the playful color scheme. The passages vouch for the intentionality of the rest. They tell us that someone who was capable of this chose that as well; and therefore we may take that as meaningful. The artist was not at war with her technique. Her technique served her consciousness.

Consider this:

First the obvious - that same funny pattern of light yellow-green on darker olive green appears again. It was wallpaper before, and now it is a view out a window. It wasn't a view out a window the first time, or the post-it would not have cast a shadow. So two different things are represented in the same shorthand. The shorthand, therefore, is a thing of pleasure or significance to Forte. Depiction is fundamental to her work, but so, we see, are odd little snippets of color and shape which live only in her mind, until she finds corners of her work to plant them in. This is a deeply expressionist impulse.

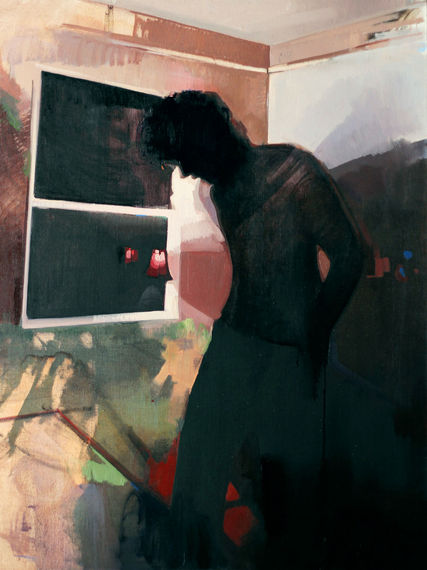

Zooming back from the window, we look at the rest of the composition. To a painter conversant with the classical techniques we have been discussing, it is a strange mix of the crude and the sophisticated. The image reveals an exquisite sensitivity to color and an expert understanding of how to mix color and how adjacent colors impact one another: look, for instance, at the patch of green light from outside which falls across the cooler indoor greys and violets of the "white" oven door. And, on the other hand, behold how little interest Forte has in blending or otherwise fancifying her brushwork. Like Manet, she has decomposed each surface into flattened planes. Unlike Manet, these planes are really very flat. I've studied them in person. They're maddening little daubs of colored paint, shape more than anything else. From a distance, they form a scene, but close up, they are just paint chips. They describe nothing at all, they seem to eclipse themselves.

These are all instances of Forte's having earned for herself the mighty arsenal of classical technique, and then chosen to run into battle armed with, one might say, a rifle and a kazoo. She took what she needed, she added some very idiosyncratic items, and from these she made her art.

In this piece, her influence shifts from Thiebaud to Uglow:

The piece shares an austere, meditative thingfulness with Uglow, and angles toward the same paradox: a vivid sense of form, of mass and presence, constructed from a set of lines and planes that are not at all shy about their flatness.

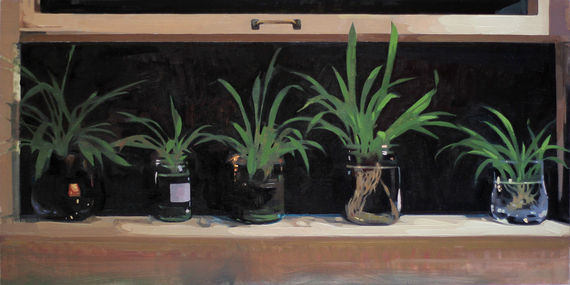

This piece vividly recapitulates how the eye scans the kind of scene it depicts: the darkness eats into the plant leaves, so that their basic shapes persist but their subtleties have eroded. The jars emerge from the gloom as an appetizing sequence of glossy highlights. Adjusted for the room, the eye can see where the overhead shines brightest on the windowsill, but cannot discern any details of the night outside.

These are all outcomes of intense observation on Forte's part. She has the classicist's patience in looking and dexterity in depicting. But she is so radical in her reductions, in eliding details and creating purely formal zones, that her project cannot be described as depicting the world. Nor do the zones serve an aesthetic purpose alone. World and formalism alike are staging grounds for her emotional state. In looking closely at life and art, she looks closer still at herself. Her eye follows her heart. There is a wistful solitude to this scene, a melancholy sense of troubles that have kept her up late, that have at last turned her away from the room, and washed her up on the shore of the windowsill, idly looking at plants deep in the night, where she is reminded of the beauty of mere things, a beauty which, just now, is much, but not enough.

All these things I see in Forte's work, and have always seen them. Her work is fun and funny and full of life, and the longer you look, the more it offers, until sadness mixes itself in as well. Her technique is like that too. It looks like slightly bookish pop art until you really look, and then you realize the trained eye of a classicist has uncovered essential truths about the mechanisms of seeing and the nature of what is seen - which the artist has woven into a subordinate position in a highly subjective matrix.

I am intensely proud that Forte is one of us. Her choices as an artist represent to me a leap forward for our odd community of representational painters. It is not necessary that there should be more than one of her. The point is that there shouldn't be, that the shared wealth of technical understanding has grown sturdy enough to support, in ways only it can, extraordinarily personal perspectives, to lend its eloquence not only to realism, but to unique self-revelations as well.

---

This essay loads down poor Felicia Forte with a lot of significance which gets in the way, a bit, of simply appreciating her work. So let's close with a couple more pieces of hers. They offer such delight.

---

All of these paintings are included in the three-person show

On the Periphery:

Benjamin Björklund + Felicia Forte + Lindsey Kustusch

September 2 - October 1, 2016

Abend Gallery, 2260 E Colfax Ave, Denver, CO, 80206