The rich get richer and the poor get bigger televisions.

In a recent article in the New York Times, "Changed Life of the Poor: Better Off, but Far Behind," the following question was asked:

Is a family with a car in the driveway, a flat-screen television and a computer with an Internet connection poor?

As the gap between the poor, the middle class and the rich widens, the answer is a resounding yes -- poor, but not as we have traditionally viewed poverty.

The article quotes Gary Burtless, an economist at the Brookings Institution, who said:

If you handpick services and goods where there has been dramatic technological progress, then the fact that poor people can consume these items in 2014 and even rich people couldn't consume them in 1954 is hardly a meaningful distinction... That's not telling you who is rich and who is poor, not in the way that Adam Smith and most everyone else since him thinks about poverty.

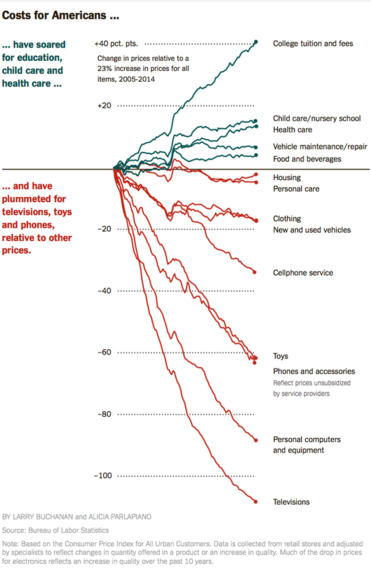

At its simplest, what we are experiencing is "what some economists call the 'Walmart effect': falling prices for a huge array of manufactured goods."

I can't afford health care; I can't feed my family through the month; I can't afford a higher/better education for myself or my children... but I am on a smartphone and we watch Game of Thrones on a huge screen.

And while the article refers to this problem in the United States, we have all seen this phenomenon repeated around the world: The slums with running sewage, undernourished kids, terrible crime and abuse amid seas of satellite receivers... listen:

"Work to survive, survive by consuming, survive to consume: the hellish cycle is complete." - Raoul Vaneigem

Quentin Hardy, a blogger, posted an interesting piece called "Valuable Humans in Our Digital Future."

Reacting to the article I quoted and shared above, he read the accompanying chart as follows:

Increasingly, the most valuable things in our world involve people looking at you, touching you and understanding you.

I loved his examples -- troubling as they are to me:

In other words, the digital elite pay money to be in contact with one another, when they could just watch the whole thing on the web. The greatest example of this, of attracting billionaires to be near one another in somewhat cramped conditions, is the annual TED conference. It's a bunch of talks and schmoozing. It costs $8,500 to attend, if they'll have you. You can watch it online in real time.

Or take music. A century ago, an Enrico Caruso record retailed for about $30 in 2014 dollars; now you can listen to it free on YouTube. It cost about the same amount, $30 in 2014 money, to see Mr. Caruso live. Currently, tickets to see Bruce Springsteen live, whose music is available for anywhere from 99 cents to nothing on the web, cost up to $1,800 on StubHub."

His view is that therefore jobs that have for years seemed to be low paying and not as attractive as tech sector work -- like nurses or teachers -- might in fact be the next up-and-coming wave of good-paying, future-proof work.

He further quotes SriSatish Ambati, cofounder and chief executive of Oxdata, a company involved in open-source software for big data analysis:

We're moving towards a 'post-automated' world, where the valuable thing about people will be their emotional content... The only way to defeat the machines is if the world, including our brains, has an impossible level of complexity that the machines can never map.

Bottom line, when digital means allow us to consume huge quantities of information cheaply, quickly and without any tethering -- analog activities with high-touch value are worth more and more.

The problem of course being that as the pressure grows (as it is) to monetize all things digital, we will see prices rising on services as we get deeper into a razor-and-blades syndrome -- give away the device -- but charge more and more for the usage, pushing the poor deeper into debt.

Frankly, if we follow this trajectory, the world of The Hunger Games starts taking on a truly horrific possibility -- not the games, but the general milieu, small groups of the wealthy living with the highest and best that technology can provide while the rest live in poverty without the benefit of the promise of said technology.

Which of course begs the question -- whatever happened to that promise?

How did curing disease end up as Flappy Bird?

How did solving world hunger become Open Table?

How did ending hatred become Snapchat?

Not that there is anything wrong with any of them (maybe Snapchat) -- I am as addicted as anyone to insipid games and love the utility of the genre of super utility apps.

As I have written about before, we are jaded and we are also privileged -- privileged to live in a world where the potential of the promise is bigger than the problem. Think on that...

And yet, in some countries fundamentalists who use technology to destroy and control, repress anything related to education and progress, and the gap widens.

So what is the lesson?

Digital is everything. But not everything is digital. Listen:

"In a democracy the poor will have more power than the rich, because there are more of them, and the will of the majority is supreme." - Aristotle

Allow me to rephrase: In a "post-automated" world.

So while the masses consume for "free" where others pay through the nose, remember, there are more of them.

What do you think?