The fun new exhibit at the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco -- Frog and Toad and the World of Arnold Lobel -- is going to make a lot of folks in the Bay Area very happy. How do I know this? Because for the last three years, a good number of you have been giving me Frog and Toad memorabilia.

It all began with Sapo y Sepo son Amigos, a really lovely Spanish translation of Frog and Toad Are Friends, the 1970 classic children's book by Arnold Lobel. For readers unfamiliar with these characters, I often describe Frog and Toad as amphibian versions of Bert and Ernie. Frog is like Ernie -- affable, good-natured, and a bit of a trickster. Toad is Bert: a little crankier, a tad more reluctant, occasionally grumpy. This book was a present from my wife right after the publication of my first Frog and Toad poem, "Frog and Toad Confront the Alterity of Otherness."

A Frog and Toad poem, you might be asking?

Let me explain.

About ten years ago, after moving from one apartment to another here in San Francisco, I unpacked an old box and came across an original hardback edition of Frog and Toad Are Friends that I remembered fondly from my childhood.

I sat there on my somewhat dingy kitchen floor and read the whole book, which was probably the first time in over a decade I'd even looked at a children's book. I was mesmerized. One story in particular, cleverly entitled "The Story," had a truly profound effect on me: It begins with Toad telling Frog he looks a little green. Frog responds that he always looks green. He is, after all, a Frog. But Toad suggests he crawl into his bed to rest. Frog does and asks Toad to tell him a story. Toad obliges, as Toads do, but there is a problem. Toad can't think of a story. He tries everything -- he walks up and down on the porch, but the story won't come. He pours water on his head, but the story won't come. He even starts banging his head against the wall, but the story won't come. By this time, Frog tells Toad is feeling better. Good, says Toad, because I feel awful, and he takes Frog's place in bed. Frog offers to tell Toad a story, and this makes Toad happy. The story goes something like this:

"Once upon a time there was a Frog who didn't feel well. His friend Toad was trying to tell him a story, but the story wouldn't come. He walked up and down on the porch, but the story wouldn't come. He poured water on his head, but the story wouldn't come. He even banged his head against the wall, but the story wouldn't come. Finally, he got into bed and his friend Frog told him a story. The End."

I thought this was genius. It was meta and postmodern and funny and smart and sweet all at the same time. It was also strangely philosophical as well as insightful about the creative process. As I sat there on the kitchen floor, I thought somebody should write a poem about Frog and Toad, and went about unpacking. A few hours later, I was thinking about the story and was visited with one of those rare moments of illumination -- wait, that person is me.

So, I tracked down several other Frog and Toad books -- Days with Frog and Toad, Frog and Toad All Year, Frog and Toad Together -- and began a Frog and Toad immersion. What I loved about the books was the various situations Lobel puts the amphibians in and how they reacted both within the context of misadventure and with each other. "Frog and Toad Confront the Alterity of Otherness" arose out of a similar desire: to see how the friends would react in an unusual situation. In this case, it happened to be contextualized with Emmanuel Levinas' concept of "alterity," from his groundbreaking work, Alterity and Transcendence. The poem explores what happens when the two creatures wake up one morning wondering about their sameness and difference.

For some reason, I kept writing Frog and Toad poems. Six or seven appear in my first book of poems, Works & Days. In reviews of the book, the Frog and Toad poems are always a point of inquiry, and in interviews, they are often the subject of the very first question. When I announce at a reading that I'm going to read a poem about Frog and Toad, there is always some sort of exclamation from the audience -- ranging from gasps to shrieks of joy. No exaggeration. And, on the rare occasion that someone asks me to read a certain poem, 99 percent of the time it's a Frog and Toad.

I tell that long story to tell this one: people who love poetry also seem to love Frog and Toad.

I first discovered this when I did a reading in Willow Glenn, California. As I took the podium I noticed there was a small gift awaiting me near the microphone -- a cassette of Arnold Lobel reading Frog and Toad stories.

The gifts kept coming.

At one reading, I was given a Frog and Toad pop-up book. Someone sent me a Frog and Toad puzzle. At another reading, someone gave me one of Lobel's other books, Owl at Home. Someone else gifted me a huge anthology of Frog and Toad tales. And yet another gave me a DVD that contained several Frog and Toad stories brought to life by the magic of claymation. I kid you not. It's pretty amazing.

And I tell that story to tell this one: the exhibit is pretty amazing too.

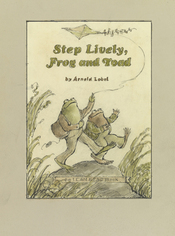

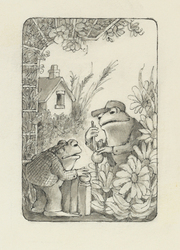

There are over 100 illustrations and works on paper, most of which are "dummies" or paste-ups of many of Lobel's books. Lobel was a meticulous craftsman. On the macro scale, he would plan out the various books in the form of a visual diagram. The exhibit features one of these maps, a kind of storyboard for a Frog & Toad collection, so viewers can see how Lobel himself saw these books. On the micro level, he would work and rework studies of his creatures. The various versions of Frog and Toad are revealing. You can see him trying to figure out just how anthropomorphic Frog and Toad should be. I've always loved Lobel for not making the amphibians too cute. I might be reading way too much into the various drawings, but I got the sense that Lobel was experimenting with that notion of cuteness. Toad especially seems bulky, sort of bulgy and balky. At times his huge eyes appear to be little loopy, as though he needs some strong spectacles.

Arnold Lobel, Study for cover of Step Lively Frog and Toad (possibly becomes Days with Frog and Toad), 1979. Graphite, ink, and watercolor on paper pasted on illustration board, 19 15/16 x 15 15/16 in. Courtesy of the estate of Arnold Lobel. Copyright © estate of Arnold Lobel.

One reason Frog and Toad have delighted kids, parents, critics, and teachers for so long (Frog and Toad Are Friends recently came in at #10 on Scholastic's list of the 100 Best Books for Kids), is the unexpected mashup of amphibian and human. Frogs and Toads are not like bears, dogs, kittens, monkeys, lions, deer, or even elephants. One is hard pressed to think of a positive Disney amphibian, and not even Richard Scarry veers from mammals. So, Toad and his buddy Frog feel fresh. They are not cuddly, but they are loveable. Lobel's ability to forge that emotional connection via slimy, scaly animals is, at its core, radical.

It might be radical, but it's not luck. The drawings are spot on -- a mix of crudeness and cuteness. The same goes for the prose style, which sort of reminds me of Winnie-The-Pooh in its straightforward but philosophical tone. There are lessons, but they are subtle. Best of all, Frog and Toad engage in real dialogue. They trick each other, they get mad, they feel insecure, and they pout. One of my favorite things about the books is how often other animals mock Toad, especially in a story like "A Swim," where Toad is neurotically self conscious about his ridiculous swimming suit. In the story, Toad stays in the river for hours because he doesn't want Snake, Mouse, Turtle, and their posse to laugh at him. The exhibit features a panel from this story -- the best one -- with Toad in his horizontally striped one-piece swimming suit standing alone on top of a boulder for all of the lake life to ridicule. Toad's expression, one of defeat, is priceless.

I have thought for many years that the designers of ET took their cue from Lobel's Frog. Look at the early drawings of Frog -- his big eyes, his alien but affable countenance, his squat dark green frame, his wide mouth -- and you see the blueprint for America's most loved extra-terrestrial. Lobel is a master in this regard. His other creations like Uncle Elephant, Owl, and Mouse (all of whom get some love in the exhibit) are less successful because they are more conventional. Frog and Toad's appeal, their acceptability, lies, paradoxically, in their weirdness.

Arnold Lobel, "And soon you will have a garden," final illustration for Frog and Toad Together, 1980. Graphite, ink, and wash on paper, 17 15/16 x 27 7/8 in. Courtesy of The Estate of Arnold Lobel.

Works from other books also appear in the exhibit. One of my favorites is Lobel's illustration of a nice Maxine Kumin poem called "The Microscope." The poem is about the Dutch inventor of the microscope, who was a contemporary of Rembrandt. Lobel's illustrations then, stunningly, resemble the Dutch master's etchings.

Lobel's facility with his pencils is notable. At times, his representations of humans can bear a strong resemblance to Maurice Sendak's. Like Sendak, he seems to skew toward rendering people via the bestial. When illustrating a collection of spooky poems, Lobel's figures look more than a little like Edward Gorey.

But, hands down, the centerpiece of the exhibit is Frog and Toad. In addition to everything I mention above, there is a small display for the popular Frog and Toad musical as well as film stills from the claymation series. There are also interactive projects for kids.

The surprise of the show for me, and the great delight, was a spiral notebook in which Lobel drafts the first version of his story "The Kite," a favorite of my five-year old son. I don't know why I was so taken by this, but Lobel writes out his story as though it is a poem. The text is lineated, just like a contemporary lyric. There are stanzas and stanza breaks; the lines never run too far out to the right. And, the story flows vertically, the way a poem might. Of course, this could be a visual decision, wanting to map out how words and images might fit on a page, but I think Lobel is thinking in verse as opposed to prose. Toward the end of the page, Toad is running with the kite, and Lobel crosses out "over the hill" and inserts "across the meadow." That's a nice change, both practically and sonically. It is moving to see Lobel's handwriting in its sharp cursive and blue ink. His penmanship looks about as unsteady as a young frog on his first trip alone into the dark woods.

There is also a paste-up from the opening pages of "The Story." This made me very happy. My joy came from the fact that I was standing in an art museum designed by Daniel Libeskind looking at framed works of Frog and Toad. In my poems about Toad and Frog I try to create interesting collisions between high and popular culture, and this exhibit in this museum -- so smartly done and so lovingly curated -- accomplishes the same thing, though on a much bigger scale and in a far more successful way. Even better, it does what my poems could never do -- canonize on a grand scale Lobel as an artist.

Even Toad would smile at that.