TED and The Huffington Post are excited to bring you TEDWeekends, a curated weekend program that introduces a powerful "idea worth spreading" every Friday, anchored in an exceptional TEDTalk. This week's TEDTalk is accompanied by an original blog post from the featured speaker, along with new op-eds, thoughts and responses from the HuffPost community. Watch the talk above, read the blog post and tell us your thoughts below. Become part of the conversation!

__________________________________________

Three trajectories came together in 2005 and took me to new frontiers of cognitive science (and subsequently, it turns out, the media industry).

• The first trajectory: I began to see an unexpected connection between my research in robotics at MIT and theories of how children learn to talk, leading to studies of child language that I did with my wife and collaborator Rupal Patel over the past decade.

• Second: The era of Big Data was dawning, and the far-fetched idea of video-recording everything that happens in a home had become a practical reality.

• Third, Rupal and I learned that we were expecting our first child in July 2005.

This confluence of events sparked an unusual study of child language featured in the first half of my TEDTalk.

Rupal and I had long discussed the possibility of capturing language development as it unfolds naturally at home. The idea was spawned from a lab study of child language that we had set up many years ago, which led us to recognize the limits of observing family dynamics in artificial settings. How could we capture data in a real home? We dreamed up a robotic system for recording a comprehensive video record of our life at home, while respecting our family's privacy. The resulting data has opened the doors for us to explore the wonders of language development in new ways. And as a byproduct, we amassed the largest home video collection in history!

Roy's son's first steps were captured as part of the world's biggest home video collection. Photo courtesy of Deb Roy.

As my students and I immersed ourselves in over 200,000 hours of home audio and video recordings, we began thinking of language acquisition as a series of "word births." With a near-complete record of life at home over the first two years of my son's life, we were able to pinpoint each time he learned to say a new word. We could then trace back in time to find each occasion where he heard that word from caregivers -- the "gestation" period leading to the word's birth.

Words with unique wordscapes tend to be learned earlier and more easily, at least for my son. This finding suggests ways that we can help children learn language more effectively by manipulating the non-linguistic contexts in which they experience language.- Deb Roy

My son exhibited a vocabulary burst starting at his first birthday, a typical phase of language development. At 19 months, however, his rate of word births unexpectedly imploded -- he slowed dramatically in learning new words even as his verbal communication skills continued to gain ground. My student, Brandon Roy, recently discovered that just as my son's word births slowed, his production of two-word sentences took off at practically the same rate. It's as if he shifted his cognitive effort from learning new words to generating novel sentences. These findings suggest deep connections between word and grammar acquisition, pointing the way to future research.

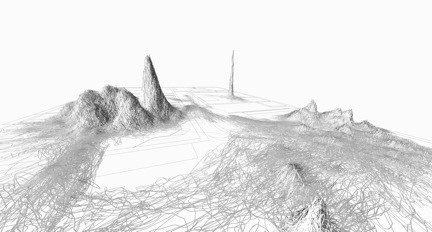

To visualize the gestation period of words, another of my students, Philip DeCamp developed "wordscapes," a collage of human movement traces extracted from all the video moments when my son heard a particular word. I showed examples of wordscapes in my TED talk, but we had yet to analyze their relationship to word births. Recently, my student Matt Miller found that wordscapes are surprisingly predictive of the timing of word births. Words with unique wordscapes tend to be learned earlier and more easily, at least for my son. This finding suggests ways that we can help children learn language more effectively by manipulating the non-linguistic contexts in which they experience language.

Wordscape that captures the context in which the word "water" was used in the Roy/Patel home. Photo courtesy of Deb Roy.

Birth of a Medium

In 2007 my research took an unexpected turn. One of my students, Michael Fleischman, decided to take some of our ideas from child language and apply them to... television. Inspired by how children learn to connect words to their visual meanings, Michael created a computer system that watched a few hundred hours of baseball games and learned to link sports commentary language ("fly ball!") to their associated visual meanings.

While we were experimenting with these learning machines at MIT, something interesting was brewing in the media world around us. People were starting to use social media -- Twitter and Facebook -- to talk to their friends and followers about what they were watching on TV. Today tens of millions of people in the U.S. alone habitually broadcast their thoughts about TV over social media while they watch.

As a result of this audience movement, we are witnessing the creation of a fundamentally new mode of human communication. One-way broadcast TV has been augmented with millions of real-time audience feedback signals that are shaping audience decisions of what to watch and how to interpret what they see. This new force promises to redefine how political campaigns of the future will be won, how marketers will sell, and over time this mass-interactive medium will give rise to new forms of news and entertainment.

In 2008 Michael and I founded Bluefin Labs to apply our ideas from MIT to make sense of all this chatter by mapping public comments to the shows and ads on TV that were sparking them. We created a technology platform that analyzes all public conversation (most of which is on Twitter) about everything on TV. Like my research on child language, Bluefin was grounded in big data science applied to human communication. The second half of my TEDTalk provided an early peek into what we were seeing.

Bluefin Labs connects audience tweets to the TV shows and ads that spark them. Photo courtesy of Deb Roy.

Bluefin Labs has emerged as a leading provider of "social TV analytics" for the media industry. But big changes are in store for us: we just announced that we have joined forces with Twitter to shift gears from measuring this new medium to helping shape its future. Watch what happens next...

New Frontiers

Massive new flows of data coupled with practically limitless computational power are unleashing profound transformations throughout the cognitive and social sciences. And even as we advance our understanding of ourselves, the same technological forces are driving unprecedented changes in how we communicate and interact with each other. All this I see as natural steps in our quest to become an increasingly self-aware and connected species.

Deb Roy is the father of two, husband, Co-Founder & Chief Scientist, @BluefinLabs and Associate Professor at MIT Media Lab.

Ideas are not set in stone. When exposed to thoughtful people, they morph and adapt into their most potent form. TEDWeekends will highlight some of today's most intriguing ideas and allow them to develop in real time through your voice! Tweet #TEDWeekends to share your perspective or email tedweekends@huffingtonpost.com to learn about future weekend's ideas to contribute as a writer.