Last fall, for the first time in our history, America's public school students were likely NOT majority white. If U.S. Department of Education projections are accurate, white students numbered 24.8 million and non-white students 25 million.

So the college student pipeline is now majority nonwhite.

In an earlier blog post, I explored some of the ramifications to higher education of our changing student body. Today, I'd like to discuss the faculty side of the equation.

Full-time college faculty, in contrast to students, were nearly 80 percent white in 2011, the latest data available. Full-time professors were even more homogeneous at 84 percent white.

So the college faculty pipeline is overwhelmingly white.

Should we care that university faculty are looking less and less like their students as we move into the future? The answer is a resounding "yes."

For diversity brings value not because of what people look like, but because our world is greatly enriched by exposure to and understanding of the widest possible range of human experience. Even more so on college campuses, where our young adults come to stretch themselves, stimulate their intellect, discover their passion, and begin to contribute to our world. Their learning environment is immeasurably enhanced when the faculty they learn from represents humanity's fullest spectrum.

And by the looks of it, we can't count on the faculty pipeline to address the disparities in faculty diversity. In addition, it looks like under-represented minorities (URMs), and in particular women, doctoral graduates are turning away from faculty positions in academia at rates greater than expected.

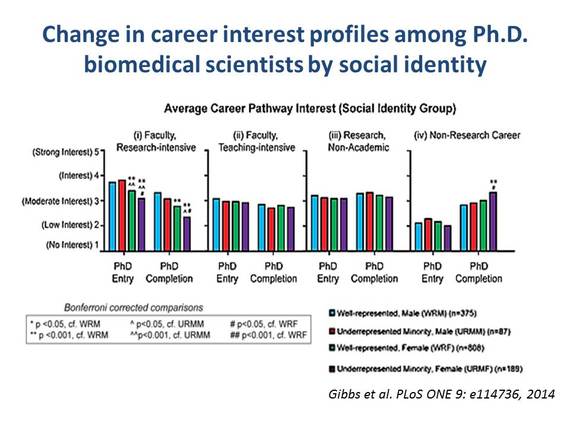

A recent study of 1,459 doctoral students in the biomedical sciences, of which 276 were URM, revealed that URM students actually demonstrated a greater decrease in their interest for faculty careers in research-intensive institutions as their graduate studies progressed, in comparison to majority (in this study defined as white and Asian) men. Women turned away from academia at even greater rates than men; URM even more than majority women.

That's moving in the wrong direction. The good news is that these differences were mostly observed for the desire to pursue faculty positions at research-intensive universities; for faculty positions at teaching-intensive universities, the decline in interest was small for all groups, and no greater for URM students.

So our difficulty increasing the diversity of university faculty is not just about an inadequate pipeline. We also seem to be losing potential faculty of color throughout their training, at least for faculty positions in research-intensive universities, such as the one I teach in.

While the study suggested various strategies to address this deficit, in the absence of additional harder data it will be difficult to develop effective strategies. For example, the study cited above, with its important observation, was simply a cross-sectional survey at one moment in time. Longitudinal studies throughout the career of URM students or young faculty would be able to more precisely identify indicators of commitment to teach in our universities.

Why is it so hard?

Building a diverse faculty is challenging for a number of reasons. We already noted the pipeline is narrow, and we may lose potential minority faculty during their training at greater rates than majority individuals. And we observed that the development of effective strategies heavily depends on good data, which we don't generally have.

In addition, a number of other issues hamper progress. Firstly, the value of diversity is generally under recognized and its benefits can be difficult to quantify and prove, so proponents have to begin by convincing others it's worth the effort. Something that isn't always easy when data are scant, the hill to climb is steep, and there are so many other pressing priorities in academe today.

Secondly, minority groups are themselves diverse and are not equally discriminated against, so there are no one-size-fits-all solutions. This requires even more data and strategic thinking.

Thirdly, we all recognize that mentors and role models are of tremendous value in ensuring the success of students and young faculty. However, another important challenge to fostering a diverse faculty is the paucity of minority mentors -- and more specifically role models -- they can turn to and learn from. For example, I recently discussed in this blog post the lack of diversity in university presidents.

Fourthly, we academics are unfortunately elitists by default. A recent study found that only 25 percent of higher education institutions produced 71 to 86 percent of tenure-track faculty. Combined with a 2012 study out of Stanford that found white students were five times as likely as black students and three times as likely as Hispanic students to enroll in highly selective colleges, it seems clear that URM graduates are at a significant disadvantage in attaining desirable faculty positions.

And finally, people often act on a perhaps unconscious human need to maximize "fit" and "comfort" in their teams, which means when you seem "different" you are swimming against one of human nature's tides. People unfortunately generally do not, at least at first glance, like "different."

What can be done?

As I reported at my recent 2014-15 Leadership Forum presentation for the Office of Diversity, Inclusion & Community Partnerships at the Harvard Medical School, at Georgia Regents University, we have pursued a deliberate and systematic strategy to increase faculty diversity over the past several years and have made real progress. Some of the guidelines we have used include the following:

- The highest leaders in the organization must be fully committed to diversity value and goals.

- Rather than focus on improving outcomes for specific groups, focus on making valuing diversity part of the broader campus culture.

- Make the business case for diversity -- explain why increasing diversity is the right business decision -- in addition to making the ethics case.

- Work to weave diversity values and concepts into the fabric of the organization; don't leave them stranded in policy manuals and institutional protocols.

- Articulate clear and transparent metrics and goals, then collect the data and share it.

- Provide appropriate funding, staffing, authority and structural organization to get the job done.

With these strategies, and the commitment of many individuals, we have been able to increase in our health sciences programs (where we have had the longest experience with our efforts) the proportion of minority faculty at our university over the past five years by nine percent and the proportion of URM students by 19 percent.

Improving the diversity of our faculty is an increasingly pressing need. We can make a difference if we strive to use systematic data-driven strategies. And we should always remember that a commitment to diversity and inclusion must start at the top of the organization.