Mark Twain once wrote, "There are three kinds of lies: lies, damned lies, and statistics." He might just as well have been talking about the weekly surveys we hear about!

The rise of public opinion polling over the last 70 years has been a boon to politicians, social scientists and newspaper reporters alike. John F. Kennedy's 1960 campaign relied heavily on public opinion polls, and every candidate since has had pollsters as an integral part of his campaign team. But what do they really mean?

In science we do 'surveys' all the time when we make measurements of some phenomenon like the mass of a proton. Physicists combine hundreds of measurements to statistically determine a better value for, say, the mass of a single proton. This is like asking thousands of people the same question, except that protons are stupid and can't help but answer the question the same way each time, every day, rain or shine. People asked the same question react differently to it, even in the way the question is asked, or what question they were asked immediately before. That is the BIG PROBLEM with all of the public opinion surveys you ever hear about.

Margin of Error

As an astrophysicist, it is difficult to understand how, from sampling 1000 people in the USA you can get an answer that is usefully representative of how the other 300 million people would respond. Protons are stupid things and this sampling argument works just fine. Across the entire universe, a proton is a proton. If this were not the case the universe would be so chaotic, life itself would be impossible. But for flesh and blood humans I find this argument that '1000 = 300 million' deeply troublesome. No two people are the same in space, or from hour to hour in time. Yet when you see the results of many national surveys they tell you the sample size and usually quote a 'margin of error' of a few percent. They would use exactly the same analysis if they were talking about protons. A thousand protons can speak for 300 million, but can 1,000 humans really do the same? Seriously?

A recent April 2014 Post/ABC News poll included 1,000 adults and quoted its margin of error as 3.5%. To statisticians, this is intended to mean that about 95% of all the additional surveys you take with this many people will yield answers within 3.5% of the ones you found for each question in your first survey. For proton mass measurements, the margin of error is also called a '2-sigma' uncertainty.

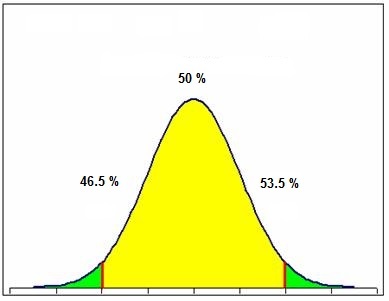

Area shaded yellow represents the results of many additional 1000-person surveys. Responses to the same question, say 50%, will range from 46.5% to 53.5% in 95 out of 100 surveys ( i.e. 50% +/- 3.5% margin of error)

Based on their sample of 1,000 people randomly selected from among 300 million in the USA, the Post-ABC poll found in March that 49% of Americans saying they supported the Affordable Care Act but in April this had changed to 44% favoring the ACA. This was interpreted to mean that Democrats will face a serious obstacle next November because of the Affordable Care Act.

But do the two surveys really support this provocative assertion?

The difference between the March and April surveys is 49% - 44% = 5%. This is only a tad bigger than the margin of error of 3.5% which means that 95% of the time you should see a March-April difference less than 3.5%. But a difference larger than 3.5% (i.e our 5%) happens randomly in about one survey in every 20 taken (Green area shown in the figure). The choice of making a big deal out of the difference between 44% and 49% is easy if you are talking about protons, but very murky if you are talking about people in a 1,000 member survey depending on what odds you are comfortable with.

Sample Bias.

Who is being polled to make up the classical '1,000' people in many of these popular surveys? The polls are usually conducted by land-line phone, but 35% of Americans no longer have land-lines. Many people do not participate in Polls for privacy reasons. Even the way the question is asked biases the results! Those that do respond to polls are by some accounts

In the recent 'Polarization Poll' of 10,000 participants announced in June 2014, Pew Research states that it pays people to participate in their polls, "We do provide a small monetary incentive to panelists for each survey they complete... Without an incentive, our sample would likely be more tilted toward the educated and affluent." This amounts to cherry-picking a population to get a subset that YOU think is a random sample. Are the opinions of this paid-for population really similar to the beliefs of a random sample, or does money add a subtle bias to defining this population and how they will respond to some questions?

With samples as small as 1,000 people you have fewer than one person per geographic/political/interest group to represent thousands of others that were not included. Many groups fall through the cracks of the selection process, not because they were a numerically small population, but because they were eliminated by the way survey members were selected.

So, in all surveys with about 1000 people or so, please do not try to overanalyze the results if the differences are small compared to the margin of error. Percentages on any question that range from 45% to 55% are all within a 50/50 flip of the coin so far as statistics are concerned. This actually implies an ambivalent citizenry from which no consensus on political issues should ever be sought, not necessarily an actual 10% difference between their opinions.

Bottom line: People are not protons so don't sample their 'opinions' as though they were!