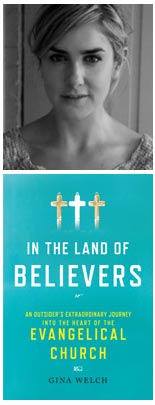

I know what it's like to be a Jew jonesing for Jesus -- at least for the purposes of a memoir. I spent a year going to 52 different churches each Sunday. So I was quite happy to find out I was not alone. Gina Welch's new book, In the Land of Believers: An Outsider's Extraordinary Journey into the Heart of the Evangelical Church, takes the reader into the heart of the religious right as Welch goes undercover at the megachurch in Lynchburg, Virginia founded by Jerry Falwell (and now run by his son.)

In the end, she came out -- as we all should -- more understanding of our religious neighbors. Her book is a great example of how those on any side of the religious, political, or cultural divide can retire our preconceived notions by walking a mile in someone else's shoes and come out a more tolerant and well-rounded individual because of it. In that sense, we should all try to emulate Welch's open-mindedness.

I caught up with Welch as she embarked on her book tour to find out what motivated her to go on this journey and what she learned from the experience.

I caught up with Welch as she embarked on her book tour to find out what motivated her to go on this journey and what she learned from the experience.

What made a self-proclaimed liberal atheist Jew decide to go to church?

My Sundays needed structure. No, I think my attraction to the church grew out of repulsion. I grew up thinking of myself as a born atheist, bristling at public expressions of faith, at being shoehorned "under God" by the Pledge of Allegiance. Berkeley was very accommodating of that attitude. For the most part, I didn't have to deal with religion if I didn't feel like it. And so from the vantage point of my little sliver of experience, I thought of our country as a pretty secular place.

The violent realization I had when I moved to Virginia for graduate school was that this is a very Christian country, with around a quarter of Americans self-identifying as evangelical. And in spite of my smug self-conception as a tolerant person, I had this calcified, unrecognized prejudice against evangelical Christians. Their politics angered me, their culture seemed silly. Most of all their vocal efforts to see the world converted to their views made me, frankly, afraid of them.

Around the time I was reckoning with this stuff, George W. Bush got re-elected, an event that was flat out unthinkable to me. The polls showed that an organized, mobilized block of evangelicals played an instrumental role in helping him secure that victory, and following the election there was an avalanche of media coverage about this scary, militaristic zombie-force of evangelicals bent on hijacking government.

So this made me feel entitled to answers: If evangelicals believed they not only had a right to meddle in what I believed, but also in how my government operated, I thought I had a right to know who they were.

There was a complicating element: I knew a handful of evangelical Christians in Virginia, and they didn't align neatly with my conception of what evangelicals were like. So I was drawn to the navigation of those inconsistencies, and to challenge my own prejudices by experiencing firsthand the tactile reality of evangelical life.

Why undercover? Why not pose as yourself -- a journalist with questions?

Before I began attending Thomas Road Baptist Church, I dimly believed that I'd attract suspicion if I presented myself truthfully. That dim sense was affirmed by my early interactions: although I didn't tell anyone I was working on the book, during the first months I spent at church I told people I wasn't a Christian, that I'd gone to Yale, that I was "curious" about Christianity. And I was greeted as the gawking outsider I was. The church members I met witnessed to me, directed me to passages from the Bible, spoke to me in guarded, prepackaged narratives.

I understood their suspicion. There's a widespread impression among evangelicals that secular progressives would like to see them flushed out of the culture. Look at the strange currency of the war on Christmas, an annual pageant of outrage that from my point of view seems like goofy satire. Many evangelical Christians buy into it because in them resides a potent fear of endangerment, for which there's plenty of real-world evidence: a lot of secular progressives treat evangelicals with derision, the media feeds a public appetite for exposes on their churches, and we celebrate when their leaders are disgraced, humiliated, or revealed as enjoying the same behaviors they built careers on decrying as sin.

So the notion that they'd trust a liberal, atheist writer to fairly represent their stories, or that they'd act naturally around me, knowing the filter through which I was viewing them, was just unrealistic.

For any undercover book, I think the only possible redemption for the methodology -- for the betrayals woven into it, for winning trust on false pretenses, for the narrative theft -- resides in the value of the result. Do the merits of the work justify the means by which it was obtained? In my case, I'd like to think the value of a detailed, humanizing portrait of evangelicals from a secular perspective, deepened by the story about how its creation changed me, meets a real deficit in cross-cultural understanding. Could it have been written any other way? No. The intimacy of my experience, which is really the hinge on which the book swings, would have been impossible had I presented myself truthfully.

Ultimately, I can't be the arbiter of whether or not my deceptions were justified. They're justified if the book connects with readers.

What was the biggest surprise you found during your journey?

The biggest surprise for me was the individual reflectiveness of church members. I think I'd had this stereotype of evangelicals as blisteringly arrogant dogmatists. But I observed instead humility and a kind of obsessive self-reflection, enacted through prayer. They call it listening to God's voice, but from it seemed to me like a constant internal pat-down of conscience, which really resulted in care with choices, and a movingly ample capacity for selflessness and generosity. I learned a lot by their example.

A secondary surprise was that I felt implicated in the ignorance I observed -- relating to gay rights, to the environment, to feminism. I started to believe that their reactionary attitudes on these subjects were a result of profound insularity, which itself seemed the legacy of a culture that rejected them: mine. Why would they open themselves up to influence from a culture that made no space for their beliefs?

Who is the target audience for your book? More specifically, do you think evangelicals -- and Christians as a whole -- will enjoy your book?

The book's appeal for secular progressives, I hope, is implicit. I think we like to think of ourselves as very tolerant, but we're comfortable being nasty to evangelical Christians. I think Internet culture has really exacerbated this attitude. It allows for hostility that would be unacceptable in life, where interacting with flesh and blood people counteracts any budding impulse to reduce someone to a disgusting cartoon. So I want this book to restore some humanity.

I'd hope that evangelicals would be interested in reading the book to see how their ideas and culture translate to a person working very hard to take them seriously, who nonetheless doesn't share their central beliefs.

Since the book has now been published, and you've been "outed", have any of the people you wrote about contacted you? If so, what was their reaction?

Well, I actually outed myself long before the book came out. I thought it was important to do my best to emotionally prepare the people to whom I'd lied, and to be available to them for questions. So I went back to Lynchburg last year to talk to some people I'd been close to, to reveal to them who I truly was and what I'd done.

Their initial reaction was shock, of course. They were understandably wounded. I hadn't known this, but they thought something terrible had happened to me. So to find out that not only was I doing just fine, but also that I'd had this agency, that I'd done something to them, that I'd been secretly recording the events of their lives and that I'd stolen them for use in this book -- I think that was deeply disturbing news. Worse, not only had I lied about being a Christian, but I was an atheist, someone who -- from their perspective -- had no moral center at all. I've tried to understand what it must have felt like to assimilate that news, but it's something I'll never fully be able to imagine.

So they were hurt, and immediately suspected I'd written a jeremiad. They wanted to know if I'd set out to embarrass people.

After long conversations about what I did and why I did it, something incredible happened: they each extended me acceptance, affection, and forgiveness. I never could have asked for that. I don't have the right to impose expectations on anyone's reaction. But they've been generous and lovely with me. I'm still in touch with a close friend from church, and with one of the pastors. I believe if it weren't for the geographical distance, I'd be in better touch with everyone.

Any ideas yet on what your next book will be?

Right now I'm working on a project based on letters my grandfather sent to my grandmother during World War II, which lushly detail his Zelig-like experiences on the European front -- on the beaches of Normandy, in Paris, in the Hurtgen Forest, at Dachau. My grandfather destroyed my grandmother's letters as he received them, so part of the work of my project is restoring her narrative as a young Communist living with her mother in Brighton Beach. My grandparents were also persecuted for their politics at the start of the McCarthy Era, so I'm working to get my arms around the scalding disappointment of that experience, to have sacrifice rewarded with vilification and ostracism.

So, you know, another light, easily accessible subject. Sometimes I wish someone would come along and force me to write some short, breezy essays.

---

Benyamin Cohen is the author of "My Jesus Year: A Rabbi's Son Wanders the Bible Belt in Search of His Own Faith" and is the content director for the Mother Nature Network.