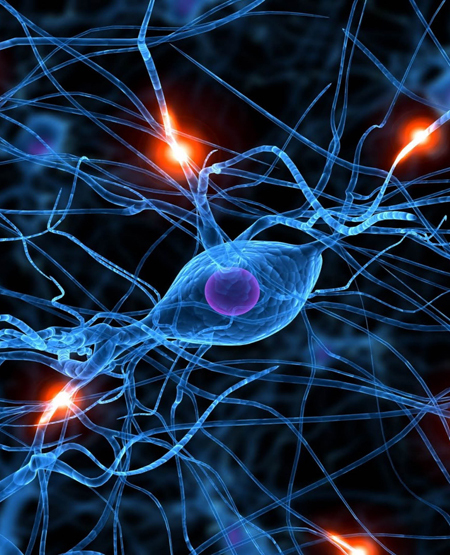

Deep learning neural net technologies / ExtremeTech

If we want our planet to be able to house 10 billion people and also want to preserve biodiversity in the future, then we need to leverage the new technologies associated with "big data" and artificial intelligence. Using these sets of new technologies, we can create a dashboard for the planet, with up-to-the-minute data on ecosystem functions continuously feeding in. We can create a unified system that "interrogates the environmental condition of the Earth," said Microsoft scientist Lucas Joppa at a conference organized by the Renewable Natural Resources Foundation (RNRF) in Washington, D.C. Unfortunately, today we are nowhere near this "Bloomberg terminal" for the planet.

Discussions throughout the conference were a strange mix of extreme optimism about the capacity of technology to solve our problems and deep concern for the state of the global environment.

While Joppa seemed pessimistic about the climate and health of our ecosystems, he lauded the potential of new technologies to be applied to ecological conservation and restoration.

Apps leveraging "deep learning neural net" technologies can enable people to quickly identify and classify plants. A site called Wild.me borrows the face recognition technology of Facebook to identify individual animal species. Through this technology, a whale shark specimen could be identified by its particular markings and characteristics. Caption bots, which are used to auto-generate captions for images, can also be tapped to label plant and animal species.

Citizen science efforts, which involve the public in conservation efforts, can scale up with the Web and big data. With Zooniverse, people participate in assessing all this biodiversity data, explained Ruth Duerr, with the Ronin Institute for Independent Scholarship.

And at the planetary scale, new satellite technologies, like the small, distributed network of satellites offered by Planet Labs, promise to make it easier to get a clearer understanding of the state of the environmental in real-time, said Duerr, creating even greater sets of more precise data.

But all that environmental data needs to be more closely connected with social and economic data if we want to get closer to that whole Earth dashboard, argued Robert Chen, a scientist with the Earth Institute at Columbia University. He pointed to his team's efforts to map settlement patterns, including urban growth. And another project maps the connections between cycles of investment in real estate and vulnerability in flood-prone areas.

Integrating multiple layers of data is the next step, as is using the data to create predictions about possible outcomes. "Big data can help jumpstart the use of well-integrated, usable data and information for managing people and natural resources. We can use data to show how real-world issues interact."

What's holding this dream back, for now, is the variable quality of map-related data and the lack of legal and system interoperability between data sets. To push that forward, he called for more work on creating international open data standards, and more lawyers to get involved to ensure "everyone who needs to has the right to use data -- that's critical."

Brad Garner with the U.S. Geological Survey pointed to the major gaps in water data in the U.S. Surface water is somewhat well-sampled, but each state uses a different measurement system, so integrating the data into a national view is basically impossible. For groundwater, there is a lack of even basic data. "We have no national sense of water use. How can we not know how much water we are using?" He was not optimistic in the near term but said the open water data initiative held promise.

And Mathew Hansen, professor of geological sciences at the University of Maryland, and a member of the NASA Modis team, explained how crucial Landsat data is to understanding climate and ecological change, and land use, urbanization, and deforestation trends around the world. NASA has purposefully made all its land map data freely accessible, so anyone can download and analyze. Many countries facing deforestation crises use the data to track illegal deforestation, and map analyses have even been used to pursue court cases against loggers.

Bringing together disparate sets of data into a unified whole planet view is a noble goal and can lead to more responsible human management of our fragile ecosystems in our era of the Anthropocene. The "bad news, however, is we're not focused enough to integrate these systems," said Joppa.

He thinks the U.S. national ecosystem assessment, which was promoted by President Obama's administration, could perhaps help kickstart the effort, at least in the U.S. He's hoping a huge data collection and analytical effort for our nation's ecosystems will continue into the next administration, given time is short to stop the worst environmental damage.

In coming years, advanced artificial intelligence can then be used to find trends and predict scenarios through big data. "We need artificial intelligence to save us from ourselves. My worry is A.I. won't come soon enough."