"...or it might mean that somehow all three are inextricably mixed together..."

"Lies will flow from my lips, but there may perhaps be some truth mixed up with them."

Let's begin with an anecdote.

At the end of August, I dropped by a local Rite Aid to pick up a new prescription. Before handing me the bottle, the pharmacist asked me if my doctor had reviewed the drug's risks with me. I'd been through this routine with other medications, and since I'd researched the drug on my own, I answered truthfully (as I sometimes do when I'm not thinking), "Not really."

She looked intently at me: "There are...a few reasons that women take this drug, but it's usually prescribed to men."

Ah -- I'd forgotten that.

After a brief, awkward pause, she asked me, "Are you planning on getting pregnant?"

I laughed. "No, I'm a little old for that!"

"Well make sure any friends you have over aren't exposed to it, because women who want to get pregnant shouldn't even touch it."

"No worries there," I laughed again, "they're all old like me."

In and of itself, I admit, it's not much of a story. Perhaps it would be better to think of it as the introduction to a longer story, for besides being brief, it does something a lot of introductions do, it presents readers with a mystery: why did I say parenthetically that telling the truth is something I do "when I'm not thinking"? Rather than answer that question, I'll deepen the mystery (such as it is) a bit: much of what I said in the above exchange wasn't, strictly speaking, true. Not all of my friends are that old, though I didn't lie about my own age (I'm 52). But my ability to bear children wouldn't be in danger even if I were a nubile sixteen year old because I'm transgender. That revelation raises further questions: why did I choose to masquerade as a post-menopausal cisgender woman? More generally, am I implying some relationship between being trans and truth-telling?

Janet Mock employs a similar narrative strategy at the start of her 2014 memoir, Redefining Realness. Granted, her initial anecdote has more intrinsic interest: a girl-meets-boy story, told with giddy, glossy sentimentality and an eye for detail. But like me, she's hiding something. "I'm afraid you won't love me once you know me, I wanted to say. Instead, I led with another truth: 'I'm afraid of getting too close to anybody'" (p. 7, italics in original). Her beau surely wants to know why she's afraid. The great majority of her readers presumably know the answer to that question already from the hype surrounding the book (or the back cover), but have others: how will he react once he knows the truth you're withholding? And when and how will you tell him?

Hooking readers with a mystery is a tried and true trick of the storytelling trade. But in the case of the stories those of us who are trans tell, it's more than a mere trick. As I'll use the above examples to bear out, our storytelling is necessarily strategic for reasons that go beyond the desire to pique curiosity. In the first place, because of prevailing beliefs about gender and the many lingering misconceptions about and prejudices against us, our truth cannot fully emerge inside conventional narratives like girl meets boy that are about or feature gender. As such, telling our stories entails "redefining" the kinds of truth those narratives can be used to tell to make room for ours. Effecting this revision successfully, moreover, requires us to proceed with an eye to our audience's misconceptions and prejudices, and to counter them as we go so that our own truth has a chance of being heard. Put another way, we must simultaneously untell stories previously told by others about us as we tell others our stories.

To complicate things still further, telling our stories isn't "simply" about separating our truth from others' falsehoods. All those misconceptions and prejudices have typically played an integral role in our stories because we've heard them too, all our lives. And we've had to untell them to ourselves again and again in order to survive psychologically while we've engaged in the painful and at times traumatic process of recognizing and embracing who we are. Our truth, in short, is "murky," to quote Mock, "layered" with the different survival strategies we've adopted along the way -- the denials, evasions, and compromises -- and the effects those strategies have had on us, unique in each case. Thus untelling you the things you think you know about us isn't just a way of preparing you to hear our truth, it's also a way of dramatizing an important part of that truth.

In sum, because of its complex relationship to our stories, our truth fully emerges only when we un/tell it to you in a way that engages you not only in the final product, but also in the process. It's by adopting a layered approach like this that those of us who are trans can answer trans gender theorist Sandy Stone's challenge from a quarter century ago to "authentically represent the complexities and ambiguities of [our] lived experience."

Let's return now to the two stories I started with. My masquerade and Mock's girl-meets-boy tale are doing the same closely related things (though in different ways): they're telling you part of our respective truths -- our concerns about being accepted; and they're untelling the same basic misconception about trans women -- that we're not ("real") women.

The concern about acceptance in my own little anecdote is obvious enough, I think. To come out and tell the pharmacist, "No worries, I'm trans," would have instantly changed her view of me in ways I had little to no way of knowing; and while my personal safety wasn't at stake in this exchange, my desire to be seen for who I am was. And here's where my anecdote, slight as it is, reveals a "murky" part of my truth: I was "masquerading" as cisgender and post-menopausal, but not as a woman. In deciding to pass myself off as I did, then, I was choosing which part of me I wanted her to see -- the female part (to me the far more important) rather than the trans part -- because I had doubts about whether she would be able (or willing) to see me as both.

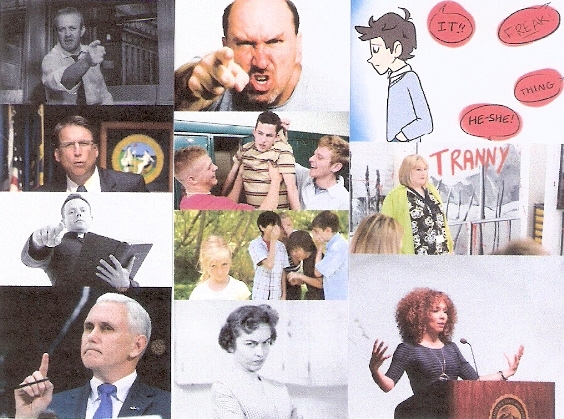

This choice, in turn, was informed by other layers of my truth that, if my anecdote were the introduction to a longer tale, I would proceed to flesh out: how the fraught conversation about "passing" influences my decisions about self-presentation, for example, and how certain reflexes, burned deep within my synapses and sinews by the virulent transphobia I internalized during the four-plus decades I was closeted, were activated in the moment I marked with the brief comment, "Ah -- I'd forgotten that." And my description of those reflexes would reenact in its essentials my own coming to awareness of them, and attempts to untell myself over the years the automatic response they spur me to: feeling like a faggot, a freak, a monster, etc.

Mock's decision to begin in New York City in 2009 rather than in Honolulu two decades before functions similarly. From the start, we're encouraged to see her in effect as her lover does: engaging, smart, attractive, a bit aloof, at ease in Manhattan's young, fashionable social spaces. And if we find her appealing, we, like he, will be anxious to know what comes after the deep breath and "I have something to tell you" with which she ends the intro (p. 11). In this respect, her beginning in the present does create some compelling drama. More basically, and importantly, though, it shows us not a young trans woman, but simply a young woman. As I did in my exchange with the pharmacist, that is, Mock chooses to present this part of herself to us as more important than her transness (and as she confirms late in the book, the choice to do so in this or any other interaction is "my decision to make" (p. 248)). Only when her womanhood is patently there in front of us does she give us our first glimpse of a seven year old named Charles, avowing this other part of her gender identity.

Opening her story this way addresses the question of her "realness" as a woman by countering a prevalent belief about gender that's fueling the nasty ongoing pushback against trans rights across the nation, genital fundamentalism. According to this belief, our gender is clearly and immutably configured by God and/or nature in our natal nether regions, and any attempt to tamper with this foundational Truth about us (read: act on our transness) is a perversion. Mock's decision flips this simpleminded script by implicitly pressing the following arguments: (1) that destinations are more important than origins -- we "proclaim, create, and evolve into who we know ourselves to be" (p. 172), not fall away from some ideal of puling newborn perfection; and (2) that our brains are the primary locus of our identity, not our crotches. And her decision does so using the same sort of "common sense" seeing-is-believing evidence that the genital fundamentalists employ. They say, "If it has a penis, it's a boy." Mock in effect responds, "If you can't recognize my womanhood, your powers of penetration are most feeble indeed." (NB: This is an argument not all trans women will be able to make as compellingly, as she freely acknowledges (see pp. xv-xvii).)

Once she transports us back to her childhood and launches into the main part of her memoir, Mock employs other strategies to un/tell her story. I'd like to consider just one of these strategies, to me the most striking: her free mixing of genres. The book's moving autobiographical episodes are peppered with passionate outbursts of political advocacy and snippets from sociological, psychiatric, and medical discourse, confronting readers with a kaleidoscope of conventional storytelling and analytical asides. The bouncing back and forth can feel awkward at times, but it's critical to her purpose of "authentically represent[ing]" her life's "complexities and ambiguities," or as she herself puts it, expressing "the murkiness of my shifting self-truths" (p. 16).

The most obvious way her use of these other discourses addresses this purpose is by directly countering readers' misconceptions and prejudices. Joining her intimate portrait of her personal struggles with gender dysphoria within a supportive if at times dysfunctional family, with statistics on the percentage of homeless/runaway youths in the U.S. who identify as LGBTQ (p. 109), for example, is a simple but effective way of putting a human face on the latter issue. The same can be said of her decision to punctuate her account of being a sex worker with brief social and economic analyses of the sex trade (e.g., pp. 205-6).

More fundamentally, Redefining Realness's narrative mashup itself mirrors or embodies the "complexities and ambiguities" of Mock's experiences, "the layered identities I carry within my body" (p. xvi). Her insistence on this "layering" runs very much counter to conventional thinking about what constitutes good writing. Prevailing wisdom about the writing of memoirs, for example, considers frequent analytical intrusions anathema, or at least bad form. Consider the following recommendations from a 2012 piece in Writer's Digest:

"A reflective voice might tell the story, might analyze events, but it tends to stay in the background, tends to let the action do the work. Research can support the storytelling, but the point isn't a display of facts or information. A memoir lays out the evidence of a life, lets the reader make the conclusions."

In similar fashion, the persistent highlighting of "complexities and ambiguities" tends to be frowned upon by both practitioners and consumers of popular storytelling. The introduction of uncertainty (mystery) does generate necessary conflict -- without it, of course, there isn't much of a story. The general expectation, however, is that the storyteller will tie up these loose ends over the course of the tale and reconcile the conflicting forces in the end -- or expel or eradicate one or more of them -- in order to present a picture of restored harmony and wholeness.

These conventional expectations are fatal to our stories, however, and to us. They evoke a not so distant past, stretching back through the centuries, when "letting the reader make the conclusions" meant far more often than not our expulsion or eradication if we dared present them with our truth. Our primary means of avoiding this fate, if we didn't remain in the closet, was to pass successfully, and to smudge out our transness by, as Stone puts it, "learning to lie effectively about [our] past," so that we could disappear into the cis majority. Erase or be erased, in short. Nor of course is this past safely in our rearview mirror. Our very existence continues to generate conflict that threatens our well being, and at times our lives, as all the stoopid bathroom bills and the rash of murders of trans folks, in particular trans women of color like Mock, in the past two years clearly evidence. The appeal of disappearing ourselves, whether by going stealth or staying closeted or taking our own lives, remains strong. All this despite the fact that the greatest threat we pose is to people's comfort. As Mock's childhood friend Wendi tells her in one of the memoir's more poignant moments, however, "Mary! Life is uncomfortable...I don't care what people say about me because they don't have to live as me. You gotta own who you are and keep it moving" (p. 117). For the psychological cost of not doing so, of "living by other people's definitions and perceptions," as Mock herself puts it later, is to "shrink us to shells of ourselves" (p. 249).

Owning who she is is no mean feat, not only because it requires courage, but also because of the incredible variety of the life experience she must embrace. Being a trans woman of color (and of mixed African-American/Hawai'ian heritage) is complicated enough, and it only begins to scratch the surface: the labels socioeconomically disadvantaged, homeless, mallrat, sex worker, honor student, elite college graduate, freelance magazine writer, and fashionable Big Apple denizen can all be affixed to different parts of her young life. How to convey all of them in a single narrative? The conventional stories about a number of these groups, and not just trans folks, are largely derogatory and require their own untelling. Moreover, many of them typically aren't paired with each other in the same person -- sex worker/NYU grad? poor trans woman of color/mallrat? -- outside of Hollywood or cable TV melodrama. Yet this is the girl who meets the boy at the start of the memoir. This is the girl who makes the decision to reveal all these layers of herself, hoping not to be rejected.

Which brings us back to the beginning of Redefining Realness. The sentimentality of the girl-meets-boy story gives it the feel of a fairy tale romance, and raises readers' hopes from the get go for a happy outcome. And on the face of it, the memoir seems to deliver: Mock comes through the trials of her childhood, completes her physical transition, becomes a successful writer, and gets her man -- a veritable fairy tale ending! Look more closely, though, and you'll see that she has begun with this old story about the most basic of human wants -- love -- in order to "redefine" it to make it capable of conveying her, and our, truth. As she reveals her life's "complexities and ambiguities" over the course of the memoir, readers are forced to accept not simply that she isn't the typical fairy tale princess, but also, and consequently, that the obstacles the prince must confront to win her hand similarly stray from the usual script. He must for example stand face to face with scars from her past that she neither expects will fully heal nor wants to forget or conceal. But the greater challenge awaiting him is a deep antipathy residing not in some distant monster's lair or in the breast of a jealous father or wicked stepmother, but in the very fabric of the culture he, she, and her readers inhabit -- a set of prohibitions, phobias, gut-level shit, centuries to millennia old, burned into his, her, our synapses and sinews. It's an antipathy of which he, like Mock's cis readers, is doubtless unconscious for the most part, and the effects of which probably neither he nor they can more than partially grasp even after becoming aware of them. Yet this antipathy has played an integral role in making her, and the majority of us who are trans, who we are. And to know her truth, our truth, those of you who are cis must step inside our complexly fractured/splintered/stratified lives and let us reveal our shards or layers to you, and untell you so many things you think you know about us, so that you might feel -- at least for a moment, in some measure -- the incommensurability at the heart of that truth.

Most readers doubtless continue rooting for the couple to stay together, and are glad when they do. But Mock insists right to the end that she wants no conventional happily-ever-after, for that would not be consistent with what she knows to be her truth: "All of these parts of myself coexist in my body...And I've learned to accept it, as is. For so much of my life, I wished into the dark to be someone else, some elusive ideal..." (p. 258, italics in original). She doesn't expect her beau to magically make her that elusive "someone else," nor does she want him to try to erase for her all the struggles and pain she endured, the denials, evasions, and compromises she undertook, before his arrival. What she asks of him instead is something far more heroic, though no more than she has asked of herself and her readers: to accept her for who she is.