Education is supposed to be America's primary engine for social mobility, but growing economic inequality is vividly reflected in our nation's top colleges. At the nation's most selective 193 colleges and universities, affluent students (those from the richest socioeconomic quarter of the population) outnumber economically disadvantaged students (those from the bottom quarter) by 14 to 1.

In our column in today's New York Times, "Making Top Colleges Less Aristocratic and More Meritocratic," Richard Kahlenberg and I argue that the federal government should require colleges and universities to admit and educate more students from low-income families. We point out that many wealthy colleges and universities with large endowments do a lousy job of recruiting, admitting and graduating low-income students. In contrast, a number of institutions with relatively small endowments (including Occidental College, where I teach) have demonstrated their commitment to this mission, in part by using their own resources to supplement federal and state government financial aid, such as Pell Grants, which cover less and less of the cost of tuition and room-and-board because Congress has been so stingy.

As Kahlenberg and I point out, there are many low-income students who have the talent to succeed at elite colleges and universities. But few even apply to those schools and those who do apply and get in often can't afford the cost.

Kahlenberg and I recommend a number of steps that policymakers, individual colleges, and donors should take to make the nation's institutions of higher learning -- especially its so-called elite schools -- look less like an aristocracy and more like the meritocracy they are supposed to embody.

Because colleges and universities are tax-exempt institutions and receive other forms of government subsidies, policymakers can and should insist that they meet some basic standards in promoting economic diversity among their student bodies. Among other things, financial aid should be based on need.

Foundations and individual donors, who also get tax breaks for contributing to universities and colleges, should also be encouraged to direct their donations to colleges that walk the walk on educating low-income students.

Many colleges and universities spend enormous resources on various amenities -- such as luxury-style dorms and (as I noticed when I recently took my daughters on a college tour) climbing walls in expensive athletic facilities -- in order to compete for affluent students who can afford to pay the full sticker price. This may be understandable but it has some troublesome consequences, including a shortage of funds to provide financial aid to the most needy students.

Our Times column in part of an ongoing debate about access to college.

The Times has done a real service in devoting considerable resources to examining these issues and injecting them into the public debate.

In May, Times reporter Paul Tough wrote a provocative article, "Who Gets to Graduate?" about how the University of Texas has developed programs to improve the odds that low-income students will succeed once they enroll. Two weeks ago, Times reporter Richard Perez-Pena wrote a provocative article, "Efforts to Recruit Poor Students Lag at Some Elite Colleges," that raised many of these issues.

Reporter David Leonhardt is now in charge of a major Times project to look more closely into these issues. His first article on this subject, "Top Colleges That Enroll Rich, Middle Class and Poor," appeared a few days ago. He did an exhaustive study of which colleges do the best and worst jobs at providing access to low-income students, and -- like Rick Kahlenberg and I -- separated out institutions by the size of their endowments to show that many wealthy colleges and universities aren't pulling their weight and aren't educating their fair share of low-income students. His table reveals this information.

After we submitted our article, the Times asked Rick Kahlenberg and I to use same Pell Grant data that David Leonhardt used in his article. Leonhardt looked at Pell Grant recipients among freshmen students only. We had originally used data for all students. At Occidental, for example, 22.1 percent of all students have Pell Grants, but Leonhardt's table shows that it has only 20 percent because it only looks at freshmen. Our article for the Times uses the freshmen data instead.

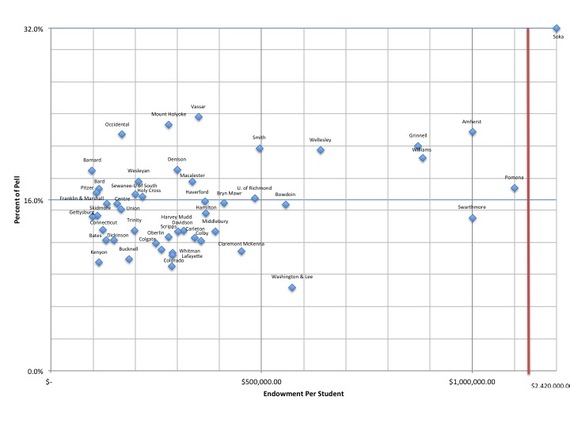

Linked here, and pasted below, is the original scatterplot diagram that Rick Kahlenberg and I created. We look at the percentage of Pell Grant students at the top 50 liberal arts colleges, as ranked by US News & World Report. We plot them based on the size of their endowment-per-student, which is a good measure of each institution's wealth and thus its ability -- if it had the commitment -- to provide financial aid to low income students.

The colleges in the upper left quadrant are those with relatively small endowments but relatively high proportions of Pell Grant students. Occidental, Mt. Holyoke, and Vassar win the prize for stretching limited resources to fulfill the commitment to economic diversity. Moreover, Occidental's commitment doesn't end on registration day. Not shown on the scatterplot diagram is the fact that 93 percent of its Pell Grant students (compared with 84 percent of students overall) graduate within six years; this is much higher than many other selective colleges.

In contrast, wealthy colleges such as Washington & Lee (where only 7.8 percent of its students are Pell Grant recipients), Claremont McKenna (11.2 percent), and Swarthmore (14.3 percent) should be embarrassed by the paucity of low-income students on their campuses.

As we mention in our article, the overwhelming majority of young American who attend college -- and an every higher proportion of low-income students -- go to public two-year and four-year institutions. But state cuts to higher education have been making it more and more difficult for low-income students to afford the cost of even public institutions.

Elite private institutions can't education all or even most low-income college students, but -- as we show -- they can certainly do a much better job of providing access to students who have the merit but don't have the money. And the federal government should provide the carrots and sticks necessary to insist that private colleges and universities fulfill this responsibility.

We also note that colleges and universities that are at or near the top of the Pell Grant rankings also have a higher proportion of students of color.

All of this debate about college access begs the question of how well our public schools are doing at preparing low-income students to attend college. That's a related, but different, topic, which folks like Diane Ravitch, David Kirp, Jonathan Kozol, Pedro Noguera and many others have been writing and speaking about for years.

Peter Dreier is the E.P. Clapp Distinguished Professor of Politics and chair of the Urban & Environmental Policy Department at Occidental College. His most recent books are The 100 Greatest Americans of the 20th Century: A Social Justice Hall of Fame and Place Matters: Metropolitics for the 21st Century.