Harlem is proudly endowed with a lustrous architectural heritage that is remarkably rich and complete. Unconscionably, it's also at risk of destruction, due to a paradoxical combination of biased disregard and gentrification. In a single section, such as El Barrio, near the majestic Harlem court house that hides a park that was the original village green 300 years ago, the profusion of exquisite details in a given singe block is extraordinary. Yet even in Harlem, the most poignant historic resources are not necessarily those with the greatest visibility or renown.

Far downtown, in February, with pomp and fanfare, a new visitors' center opened near the 'Negro's Cemetery' rediscovered in 1991. Active during the 17th and 18th centuries, it was the final resting place of tens of thousands of African slaves whose unpaid labor helped make New York the nation's great commercial capital.

"It's shocking -- the number of people today who are still unaware that this history exists in New York," said Tara Morrison, superintendent of the African Burial Ground National Memorial.

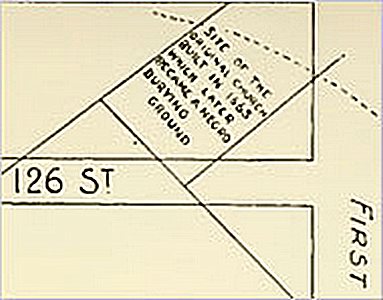

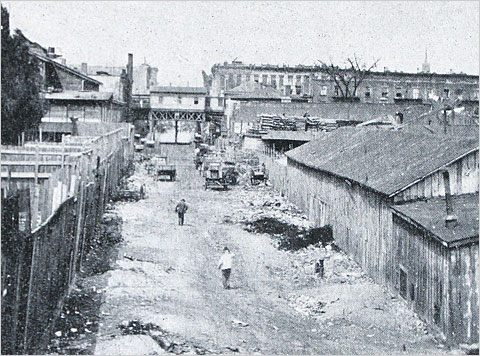

Uptown, far less well known, yet another 'Negro's Cemetery' lies in East Harlem. What is now the Metropolitan Transit Authority's 126th Street bus depot sits atop this colonial-era burial ground for African slaves and free blacks. It occupied a quarter-acre lot on the original Dutch Reformed Church grounds (First Avenue between 126th and 127th Streets). This cemetery remained open until as late as 1845.

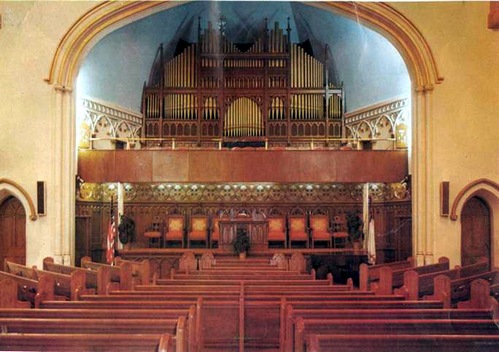

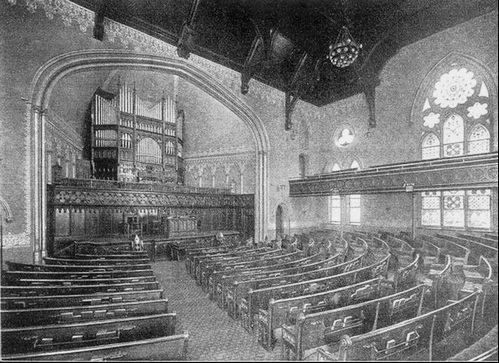

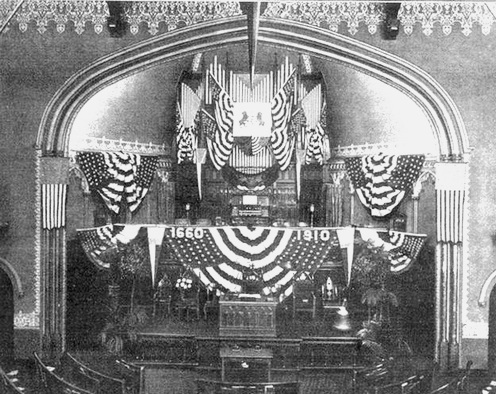

Harlem 's oldest church organization also holds the record for having the longest duration of continuous worship here. It was organized in 1660, two years after a permanent settlement was established. During three eventful centuries this Dutch Reformed congregation has occupied seven edifices at three locations.

The first was positioned obliquely, near what is now First Avenue and 126th Street. Dutch colonists, initially establishing Neiu Haarlem in 1636, introduced African slavery here by 1626. This first church site was later the location of their churchyard, comprising separate cemeteries for blacks and whites, side by side. When these parcels were sold for development in the 1870's, records show that church officials directed that the remains of whites be disinterred and re-buried at Woodland.

Black remains were left in place to be repeatedly built over. And this is why many community leaders fear the historic burial ground might be lost or defiled, due to ongoing work expanding the Willis Avenue bridge, and a plan, to begin in 2015, that will entirely rebuild the city bus facility.

Responding to constituents' concerns, State Senator Bill Perkins and State Senator José Serrano conducted a public hearing on Friday, March 19th at the Elmendorf Church, which is the successor of Harlem's original Dutch Reformed Church. Featuring informative agency officials and an impassioned audience of over 100 residents, this proceeding investigated the impact pending public construction projects might have on this important remnant of New York's multi-cultural heritage. They also examined how best to implement official action to protect Harlem's neglected and invisible landmark.

Expert testimony included statements from journalist and HBG Task Force member Eric Tate, scholar Christopher Moore, who gave a power-point history of the burial ground, and the Schomberg Center for Research in Black Culture Director, Howard Dodson.

The best news of the day came from J. Winthrop Aldrich, Deputy Commissioner for Historic Preservation at the New York State Parks Department. "Our advisory committee have recommended that the Elmendorf Church be listed on the National Register of Historic Places." he announced to cheers, saying he had every expectation that this would happen.

Asked by Senator Perkins if, the possibility that grave-sites had been disturbed over the years, 'does that preclude designation of the African Burial Ground on the National Register of Historic Places?', an equivocating Mr. Aldrich finally conceded that, while ordinarily this might be true, that the extraordinary significance of this landmark meant that it was possible to argue that notable history overrode issues of material integrity. To this Senator Serrano powerfully expressed the sentiments of most, declaring, "even if due to earlier construction, there are no remains there at all, they were there, so the burial ground should be landmarked anyway!"

As welcomed as Commissioner Aldrich's announcement about the church, was the MTA's testimony that they would soon begin an archeological survey of their section of the burial ground site, preparatory to the bus depot reconstruction project.

Christabel Gough, of Greenwich Village's Society for the Architecture of the City said that research she had undertaken suggested that remains at the MTA section of the burial ground were, more than likely, entirely intact. But it was the HBG Task Force's secretary, and Elmendorf Church Elder, Deborah Gibson, who best summed up what all of the community's concern, Senator Perkins and Serrano's hearing, and even landmarking and historic preservation, are all about, saying,

"I need to be able to go to Harlem's African Burial Ground, to see it and to touch it, with my grand children, so that I can teach them about the lives and deaths of their ancestors. I need to do this for them and to remember our people, and a mere plaque, will not do!"

In New York State slavery, gradually abolished in 1827, persisted until 1830. Much of what we know about the City's black burial plots is due to London native Reginald Pelham Bolton, considered during his lifetime as the foremost authority on the early history of Harlem, Washington Heights and Inwood. An acclaimed civil engineer, with volunteer crews he was able to excavate many acres of rural land in northern Manhattan. Pursuing Native American and Revolutionary War relics, he found thousands of artifacts of the Weckquasgeek Indians, Revolutionary soldiers and of enslaved Africans.

An amateur in the old-fashioned sense that once defined the Olympic games, Bolton documented hundreds of skulls in slave burial grounds. Nails found among the remains indicated that bodies had been interred in wooden boxes, while the presence of brass pins and green stains on the skulls indicated that shrouds had been used. Otherwise, the sad end for these slaves was dispatched with relative simplicity.

Laws prohibiting any showy ceremonies conveying dignity and respect were of course meant to demean slaves, codifying lowly status. "No pall, gloves, or favors of any sort are to be worn, and any slave who is found to have held a pall or worn gloves or favors shall be whipped." it was decreed. [During the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, gloves, black arm and hat bands, lockets and rings containing the deceased hair and other 'mourning jewlrey' were traditional mementos distributed to mourners attending funeral services. Prohibitions regulating the time of burials or the number of mourners allowed, served a more practical purpose. A law passed in 1722 mandated that all negro and Indian slaves dying within the City should be buried by daylight. The law was subsequently rescinded and a new edict stipulated that not more than twelve slaves should attend any slave's funeral, under penalty of a public whipping.

Plain old hysterical fears of slave conspiracies inspired such restrictive laws. But what motivated the initial reluctance of colonists to convert 'Indians' or African slaves to Christianity, as Bolton notes? Indifference to civilizing 'savages' through religion arose from an implicit right to manumission, the promise of freedom and salvation, that baptism was deemed to provide, even to a slave. Hence Bolton observed, "It was the custom in the old slavery days hereabouts to inter the remains of bond servants in a plot set apart for that purpose...", stressing how such places occupied unconsecrated, unholy ground, regarded as the due of pagans. Refused Christian burial and its rites, some slaves at least, were probably able to adhere to the burial rituals and customs of their ancestors.

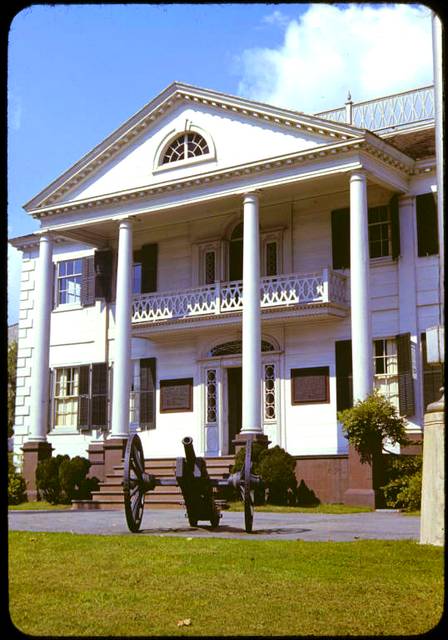

Often, having capital reserves on hand, the affluent are able to avail certain economies that elude the rest of us. A slave two centuries ago cost about $30 dollars, which represented almost two months' wages for a white laborer. Moreover, among the elite, entire retinues of African slaves were considered fashionable status symbols. At Mount Morris, one of the grandest country estates in the vicinity of New York, they predominated in the household. Built in 1765 for the Morris family at today's 160 Street, it is the oldest surviving residential building on Manhattan. For a brief time at the start of the War of Independence, Mount Morris served as Washington's headquarters. General Washington's slave, William Lee, his valet, and his cook, Miss Thompson, stayed with him during his five-week visit at the house.

Pierre Toussaint, currently being examined for sainthood, exemplifies these enthralled servants. As a butler, he accompanied his Haitian Revolution-refugee masters to New York in 1787. Trained as a hair stylist, and becoming the most sought after in the city, Toussaint earned a handsome income, which he devoted largely to maintaining his masters.

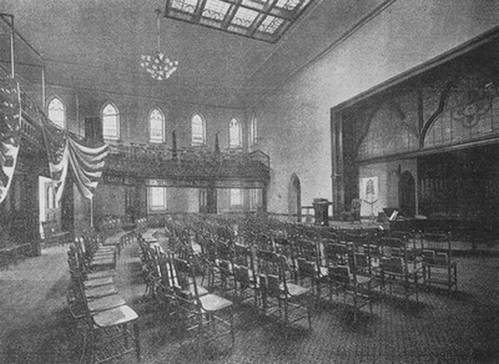

Harlem's fourth Dutch Reformed Church, built in 1824, at Third Avenue and East 121st Street, designed by celebrated architect Martin E. Thompson, was their most elegant . Altered by Thompson in 1852, the lengthened church acquired a chancel behind a columnar screen and an Ionic portico.

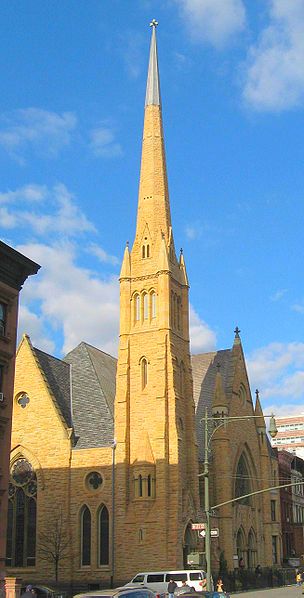

Sadly then, as Third Avenue became the city's first street paved from the Battery to the Harlem River, and a major commercial strip, this commendable structure was first moved in 1882, and then demolished in 1908. By 1887 the Dutch Reformed congregation had already followed its prosperous parishioners west and erected a new Victorian Gothic edifice, designed by John R. Thomas, at 267 Lenox Avenue.

Their old church and a new parish house survived as a settlement house, meant to evangelize among poor European immigrants, was renamed to honor the mission's founding pastor, the Reverend Joachim Elemendorf.

Clad in golden Ohio sandstone, the most conspicuous feature of the new gargoyle-embellished Collegiate Low Dutch Reformed Church of Harlem was a soaring, slender spire, 'the finger of God,' old-timers said. Transformed into the home of an African American congregation, in 1939 it became the Ephesus Seventh-Day Adventist Church, with a thousand members and a mortgage paid-in-full, by 1945.

On January 9, 1969, disaster struck. A fire started in the roof of the Youth Chapel and quickly spread, ravaging the church. Except for three stained glass windows, the entire interior, with its intricate timber-framed roof, was destroyed. Weakened by the blaze, the steeple's top 30 feet were removed to prevent it from collapsing. While the church was rebuilt (1969-1978), members worshiped at St. Andrew's Episcopal Church at 127th Street and Fifth Avenue.

Extensive rebuilding by a determined congregation has already cost several million dollars since 1978. These heroic efforts culminated in December of 2006, with restoration of the long-truncated steeple. Overseen by young church member Allen Price, working closely with preservation architect Page Ayers Cowley, this undertaking introduced a replacement pinnacle of lead-coated copper and steel.

Far from being satisfied by the phoenix-like reinstatement he has helped to accomplish, Mr. Price, day-dreaming aloud, speaks, filled with faith, of being able to help convince his fellow church members to do inside what they have done outside,

"I would love for us to recreate some of the beautiful interior we lost during the fire. Of course it wouldn't be easy. But then, some said that we could never bring the spire back, either. Fortunately our minister said, 'With faith, all things are possible,' and of course he's right about that."

For additional information about the joint hearing of Senators Serano and Perkins, please call 212-828-5829 or 212-222-7315