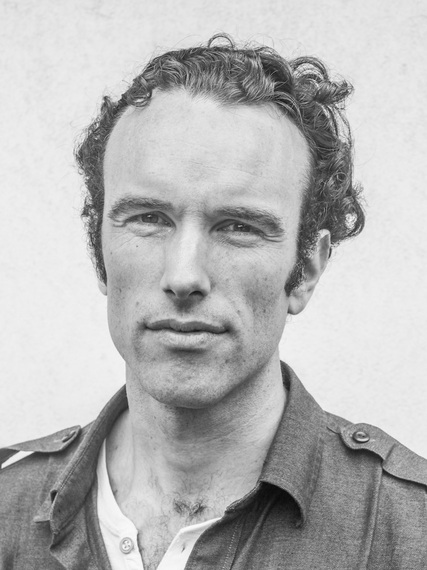

Elliot Ackerman is a decorated veteran of the Iraq War and the War in Afghanistan, and now the debut author of a remarkable novel, Green on Blue, out February 17 from Scribner. Green on Blue is narrated by a Pashtun teenager named Aziz, who describes the state of his country as such: "In Pashto, [our] type of war is called ghabban: this is when someone demands money for protection against a threat they create. For this type of war, the Americans don't have a word. The only one that comes near is racket."

Beyond its harrowing and finely-wrought depiction of the impossible choices average Afghans must continually make, what makes Ackerman's novel an important one is this sort of translation it offers for the contemporary Afghan experience writ large. For the West, in which violence in Afghanistan is often assumed to be driven by religious zealotry or nationalist anger, Green on Blue deciphers the degree to which it is instead driven by the simple instinct for survival.

Ackerman's Afghanistan is one of eternal violence between militant groups and individuals, with a bloodiness, sophistication, and savagery amplified first by Russian military occupation and its attendant infusion of weapons and entanglements, and now by the American version thereof. The traumatized tenor of the population announces itself in Ackerman's description of some of the wounded after a bomb goes off in a bazaar, who "looked at their broken bodies with curiosity, as if in a new suffering existed a chance to escape the old one."

Aziz is thrust into the turmoil at the age of ten, after militants kill his family and he and his older brother Ali are forced to become beggars in the local bazaar. When Ali is castrated and loses a leg in a bombing orchestrated by the militant commander Gazan, Aziz agrees to join a militia to pay for Ali's shelter and medical treatment.

The militia is filled with young recruits like Aziz, who are lured by the chance to take "badal" -- a socially conditioned channel for traumatized fury that means revenge in Pashtunwali -- on those who have hurt their families. Nationalism motivates no one. "We fight for the [honor] of our homes," the soldier who recruits Aziz tells him, "but for no government." We are given no reason Aziz should care about a government that doesn't seem to care about him -- in the remote region where Aziz is from he is counted and considered by a protective entity only after joining his militia.

This militia, called the Special Lashkar, is backed by the Americans, which gives it enough firepower to allure recruits with the promise of permanence in their otherwise volatile worlds. The Special Lashkar casts itself as a surrogate family that would never desert those loyal to it. "Who would call you destitute now?" The Special Lashkar's Commander Sabir asks two orphaned brothers. "When one family is taken, another is provided," one of the brothers answers with heartbreaking verve.

It becomes quickly apparent that this surrogate family exists to generate profit rather than to offer opportunities to exact revenge. Commander Sabir is a waypoint on a loop in which villages are shelled by militants funded by commanders who want to build outposts to "protect" those villages so they can get kickbacks from American-funded contracts to build those outposts. Sabir's explanation for perpetuating this violence has a logic most Americans don't have to understand: "What justice if we lose control of [Gazan] and never build the outpost? The Americans will no longer need us - how will we survive then?" Green on Blue forces us to send Aziz back to begging in a bombed-out bazaar if we root for him to reject Sabir's reasoning. "The... loyalty we had for each other, or the hatred we had for Gazan, all of it seemed of much less concern than the meal in front of us, and tomorrow's." Aziz tells us. "...As long as I stayed a soldier and my pay went to the hospital, my brother would be cared for. My war was as simple and honest as that."

With the path to any sort of societal honor increasingly opaque, we see in an especially poignant smattering of moments some characters try to establish and live by codes of personal honor. When Aziz is forced to leave the Lashkar and work for an intermediary between Gazan, the Americans, and the Lashkar, he stays in the hut of an old and destitute man named Mumtaz who has declined to take part in the war machine. Mumtaz tells Aziz stories of life before the cycle of perpetual conflict began in Afghanistan, and as the two men become close, urges Aziz to extract himself from the violent scaffolding beneath him. When Aziz assumes a significant role in sustaining that scaffolding, he knows "...at some point [Mumtaz would] learn of those choices. This made me never want to see him again."

Even the Commander Sabir is touched by personal failure from which no profit can be extracted nor revenge exacted. When his pet goldfish, Omar, dies from being overfed with rice when the Americans don't deliver his fish food as usual, Aziz notices that "Commander Sabir's eyes wandered the room... and in their avoidance I saw his little shame at being unable to care for his companion." Most of the attempts we see to construct these voluntary relationships and do them justice end in failure, no match against the chaos of lives constructed to acquire advantage conferring the reality or illusion of safety.

Personal honor seems instead like a luxury that has been washed out of the fabric of rural Afghan life. Refusing to participate in the war machine doesn't protect a village or home from being shelled, and more often than not we are shown this refusal resulting in punishment for the refuser and their family. What kind of paradox is this to ask a preteen boy to solve? In the developed world, we encounter this kind of dilemma in an essay prompt for a philosophy course. Green on Blue's moral strength lies in showing us how unqualified the low stakes of whatever answer we give renders us to pass judgment on those for whom the stakes couldn't be higher.

As Aziz watches Gazan's starving young fighters drag steel mortar tubes through the brush of the mountains, he wonders, "If they had any capacity to imagine another life. If they didn't, this was their greatest suffering." If Green on Blue suggests the West can do anything to break this cycle of violence, it is that it should be through propagating the idea that a less violent and futile way of life is possible, using evidence from Afghanistan's own history, which Mumtaz urges Aziz to study. "Know these stories so we can remember a way that is different than now," he tells Aziz. "The future is remembering."

The corrosive effects of a life engineered around survival pervade the pages of Ackerman's novel, and not only demand empathy from his readers, but also brings it out in them. His is morally fine and commanding writing, a powerful response by an American soldier to his experience in a country where almost any amount of power is overwhelmed by the racket.