On Sunday afternoon, October 21st, world renowned pianist András Schiff returns to San Francisco's Davies Symphony Hall to play Book II of Johann Sebastian Bach's The Well-Tempered Clavier. The concert is part of Mr. Schiff's 2012/13 residency as a Project San Francisco Artist and in conjunction with his Bach Project in North America, a three-part tour that will conclude at Carnegie Hall in November 2013. In San Francisco, Mr. Schiff has so far presented The Well-Tempered Clavier, Book I and Keyboard Concertos No. 1 and 2, as well as leading the SF Symphony Orchestra in Mendelssohn's Hebrides Overture, Symphony No. 4, and Fingal's Cave.

"Mendelssohn resurrected Bach in 1829 when he did The Saint Matthew Passion," said András Schiff during our recent visit. "This was a revolutionary event, because not only did he bring Bach back into circulation, it also drew a line that said -- From now on! We are also interested in music from the past. Not just what's new."

Mr. Schiff returns on April 14th to play the complete French Suites and again on Sunday, April 21st for the complete English Suites. Mr. Schiff took the Grammy Award for his recording of the English Suites and this past September released his second edition of The Well Tempered Clavier Books I and II for ECM Records. "The Well-Tempered Clavier is as great a work as I have ever come across," he said. "It is a universe."

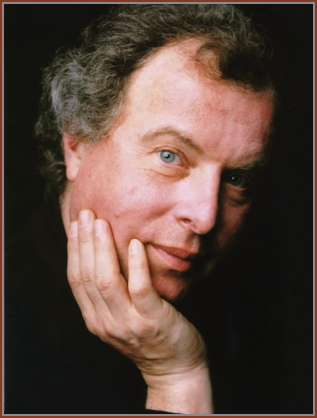

ANDRÁS SCHIFF. Photo, Sheila Rock

The next stop for the Bach Project is Los Angeles and the Walt Disney Concert Hall on October 24th. There is room to ponder a bit of irony here. From just prior to the birth of the Baby Boomers and now to their grandchildren -- many people's first exposure to Bach is through Walt Disney's 1940 animated feature, Fantasia, and its grand opening sequence -- Bach's Toccata and Fugue in D Minor. The film's conductor, Leopold Stokowski, led the Philadelphia Orchestra in his stunning arrangement from 1927 -- a transcription that remains vital, bold and completely seductive. For some film buffs, it has always taken a while to experience the work as Bach originally intended it -- on the best organ available in the largest church in town.

"I started taking piano lessons when I was five," said Mr. Schiff.

Luckily, Bach was a great teacher and pedagogue and had lots of children. Twenty-one. And so, he wrote music for children, like his little preludes and dances from the Notebook for Anna Magdalena Bach-. I loved them immediately, and then other pieces I heard on the radio -- such as the Toccata and Fugue. I heard it first on the organ before I saw Fantasia. Things like The Brandenburg Concertos were very appealing to me. It took a long time before I heard something like the Saint Matthew Passion or B minor Mass. But the thing with Bach -- from the smallest work to the largest - is that it follows a logical line. You can get the greatest of Bach in a nutshell, as with the Three Part Inventions -- in two minutes! You will find the same in the huge, very monumental works. It's just always been there with me. I've felt the immense strength of his music, the spiritual strength. Whether you are a religious person or not -- Bach was a religious person. And you feel this rock solid belief. It's an uplifting feeling, not something that restricts you. It is a huge belief that liberates. It is very, very human and full of life. There is also a very strong rhythmic element that I always felt as a child. The music pulses and swings in the dance movements. There is a lot of dance in it, and it's not always brought out adequately in performances. His music should not be performed in a dry and academic way, but in a liberal and universal way. I find it has an incredible appeal to people, to younger persons who don't necessarily love Classical music. But they love Bach. They resonate with it as they listen.

ANDRÁS SCHIFF. Photo, courtesy of the artist

"I had exposure to classical music in my family," he said.

They were not professional musicians, but my mother was trained as a pianist and my father played the violin. Music was just there in the family. At school, I was more or less the exception - which is not always good. The other kids loved popular music. You don't want to be the odd one out. This was during the early time of the Beatles, when I was growing up in Communist Hungary. It was not so easy to get access to popular music from the West, from the United States. You had to listen to radio stations like Radio Free Europe which would broadcast their music because they knew young people were very hungry to hear it. Otherwise, in the Communist countries, this music was not easily accessible. So, of course I listened to it. I learned to play it. If you wanted to make a good impression with the girls, then you don't play Bach or Mozart. Jazz was an element that was certainly available. But if I played them a Beatles song or something by the Rolling Stones, then I made some very big points. Operettas were very-very much alive. This was a heritage from the Austro-Hungarian Empire and we had an operetta theatre. Also, folk music. I always loved and still love the folk songs. When I was growing up in Hungary, the great composer Zoltán Kodály was alive. He was an old man and not composing much anymore, but put all his energy into education. He said, "All children should learn and sing folk songs whether or not you have a beautiful voice." Because singing is essential. He left a wonderful method and the country benefited from it. Unfortunately, the effects of that are now almost gone. But for many decades you could feel that people were interested in music. Young people were coming to concerts and it was an integral part of your life.

There is much to be said about a first-time experience of Bach in an ideal and exciting setting, especially when it is presented by a long-established master such as András Schiff. Other venues for his 2012/13 Bach Project include New York's 92nd Street Y, Avery Fisher Hall and Alice Tully Hall; Chapel Hill's Memorial Hall in North Carolina; the Chicago Symphony Center; and The Royal Conservatory in Toronto. For both the new and seasoned listener, musical adventures such as these can transport the heart and imagination to a totally other level. I asked András what he thought Bach's reaction would be to hearing his music played in the vastness of Davies Symphony Hall.

I think he would be shocked. A concert, as we know it today, didn't exist in Bach's time. The church was the main venue. He played the organ. He was employed by the cities, the last being Leipzig. He had to write for the Sunday morning service -- a new cantata every Sunday. For his instrumental music, the more intimate music, a lot of it is for teaching material - like The Well-Tempered Clavier. It was written for very advanced music students to study the art of counterpoint, the art of composition, and playing fugues in different keys. So, Bach is a great pedagogue. Also, a great scientist. He looked at music as a science -- the art of tuning in all equal temperaments, to write twenty-four preludes and fugues in all the major and minor keys. This was revolutionary. But he did not think of performance. He also did not think of posterity. So, he would be very surprised that we are playing his music today. And by all means, if you have a great concert hall like Davies, with over 2,700 seats -- he would be pleased, but very surprised. When Bach was playing on the klavichord, it was for a handful of listeners. That's it. In drawing rooms. He was writing this more intimate music for the connoisseurs and the music lovers, the amateurs who would play. And it shows a great musical culture at that time because, if you look at the number of people, it's miniscule compared to today. We're talking about a few hundred people in a city or a few thousand in all of Europe. But still, this was a very high level -- a circle of music lovers who were always looking for the newest. It was, 'What did Mr. Bach write last week?' -- not, last year. And whatever somebody wrote fifty years before was yesterday's weather.

Today when everything is in flux about the creation, promotion, and accessibility of all genres of music, I asked Mr. Schiff to speculate on a film script -- a chapter in the life of Johann Sebastian Bach, an episode that would show how he adapted to changing times.

"When Bach was sixty-five," he responded, "that was not a young age."

Today it's nothing. But in those days it was substantial. He had already witnessed -- let's say during his last ten or fifteen years, when he was in Leipzig -- that the world had changed. For example, his son, Philipp Emanuel Bach, who was a wonderful musician and composer, was writing in a totally different style. Like a forerunner of the Classical period, the time of Haydn and Mozart. People were already saying to Bach that he had to move on, the world was changing. Bach couldn't just jump out of his own skin. He stayed consistently true to himself. So, he wrote in his manner even more radical pieces. His last compositions, The Musical Offering and The Art of Fugue are his two most radical ones and he wasn't really writing this for the public. I don't think he could move on with age. He's not somebody to change his nature. But then, his time comes again. Today, he is more alive than ever.

Enjoy András Schiff play the Bach French Suites and more: